'This is the best moment of my life,' he said, lying in the bath: Ian Holm remembered

That sense of emotional ruthlessness was what made him such a brilliant Lear

Richard Eyre

Ian Holm was, as it was so often said, the actor’s actor. Not because he was virtuosic, meticulous, droll and charismatic, all of which he was, but because he always drew the audience in, he always withheld something mysterious – something under the skin, something of the soul – and the audience always came to seek it. It’s no surprise that he was Harold Pinter’s favourite actor.

Related: Ian Holm, star of Lord of the Rings, Alien and Chariots of Fire, dies aged 88

I saw Ian first in 1964 playing Henry V and Richard III and was entirely capsized by his energy, his bravura skills and his wit. Seeing these performances – along with Paul Scofield’s Lear two years earlier – was what made me begin to think that I wanted to pursue a life in the theatre.

Ian wasn’t hard to love. He was funny and modest and a constant enthusiast for whatever he was working on, or a piece of music he’d heard: “Claudio Abbado, what a conductor!” – or something he’d seen: “You must see the National Theatre of Brent,” he’d say, “Jim Broadbent is a genius!” He was very open with his feelings but, paradoxically, very reserved with them even though entirely frank about that reserve. Falling in love, remaking his life and falling in love again was the pattern of his life. “I always forget the pain and the past,” he said. Perhaps that sense of emotional ruthlessness was what made him such a brilliant Lear.

Paradoxes are the oxygen of good actors and the most important one is to look spontaneous and at the same time keep a corner of the brain actively deployed as a monitor, cold, detached, critical and unengaged. Ian had that characteristic in spades. When we were rehearsing the “mad scene” – the exchange between Lear who has lost his mind and Gloucester who has lost his eyes – Ian was being achingly brilliant. “Give me an ounce of civet, good apothecary / To sweeten my imagination. There’s money for thee,” says Lear. “O, let me kiss that hand,” says Gloucester. “Let me wipe it first; it smells of…” Ian stopped. Minutes seemed to pass.

This wasn’t acting; this was being, this was possession. Then he turned to me and, with an impish grin, said: “What’s the word? Oh, mortality, of course.” Which, given that he had a photographic memory, was another paradox. And after this moment, like a violinist picking up his bow, he returned to the same point in the scene, first beat of the bar, pitch, tempo and intensity perfect, no shuffling, no prevarication. That’s the true actor: the true professional – experiencing the state of possession, enduring passion and yet, like a firewalker, remaining untouched by the experience.

When I asked him to play Lear in 1996 he had hardly been on stage for 15 years and had not played Shakespeare for 35 years. We talked about love of family, of children, of parental tyranny – different only in scale from the political variety, of failing to express love. And we talked of madness. “That’s the easy bit,” said Ian. Perhaps he was referring to his familiarity with insanity – his father was a psychiatrist in a mental hospital – or perhaps he was hinting at his experience of stage fright, when he lost his nerve, a neuron away from losing his mind.

Rehearsing Lear, Ian was like a fit dog gnawing at a bone. He became obsessed, always thinking constructively, never perverse or nit-picking. “When Lear talks of being ‘unaccommodated man’ he must be naked,” he said, “anything less would be dishonest.” Before the first preview he stopped me: “I think I know how to do the ‘Howl’ speech. See what you think.” And he did know how to do the ‘Howl’ speech: he carried Cordelia’s body on and instead of putting her down before he spoke, he stood with her corpse in his arms and howled at Kent, Albany and Edgar. The four ‘howls’ emerged as an order, a command, the indictment of a father - don’t be indifferent to my suffering.

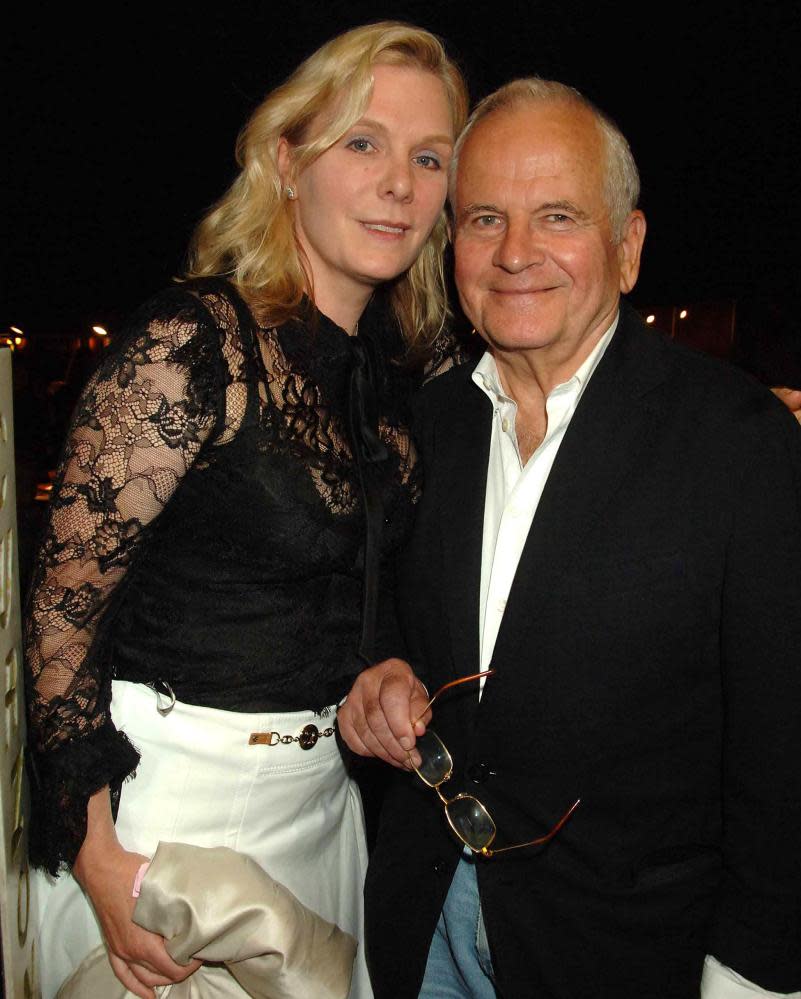

After the show on the opening night I went to see Ian in his dressing room, where he was lying contentedly in his bath. “This is the best moment of my life,” he said. When he died I had a message from his Cordelia, Anne-Marie Duff, with this photograph attached.

“What an honour that was,” she said. I felt the same.

He was sort of like a little dog: really hungry to play

Anne-Marie Duff

There’s always quite a strong bond between the actor who plays Lear and the young actor who plays Cordelia. It’s such a powerful relationship on stage, it’s bound to bleed into one offstage. That was the case with me and Ian. We hit it off immediately: from the get-go he was so warm and authentic and made me feel important and that what I had to say was valuable. That doesn’t always happen when you’re starting out, with people who have been around the block.

But Ian was really interested and engaged. A director once said to me that the two hardest-working people in the room will always be the youngest actor in the cast and the lead. One is so hungry and the other is so dedicated. If I ever came up with an idea he’d go: yeah, tell me more, tell me more. He was sort of like a little dog: really hungry to play. He’d be really helpful and a great teacher but at the same time playful and brave and up for doing things differently.

He kept curious, and that was key. Once you stop being bothered you’re screwed. Great artists seem to doggedly hold on to curiosity and he was a great artist, in all mediums. He shone on stage, on TV, on film - there wasn’t an arena in which he couldn’t perform. That’s another sign of someone who’s just good at his job.

Ian was also very mischievous, which made him feel super-young. He was cheeky, but there was nothing lascivious about him. He was funny – which I think is insanely attractive. He’d tease me if I was getting too self-righteous; would be first to raise an eyebrow from across the room which would just make me laugh. That’s an act of generosity in itself. It’s a lesson: don’t take yourself too seriously.

He worked so hard every single night, there was never one show he was in a lower gear

I did have a sense at the time that the production was a career highlight. When he first came in, he knew every single word of the whole play. It was part of his youthful energy – he still had hopes and dreams to be fulfilled. It wasn’t: “Well, I suppose it’s my time to play Lear”, but “Oh mother of God! I’m playing King Lear at the National Theatre!” He worked so hard every single night, there was never one show he was in a lower gear. Always and ever full force.

The people who’d come to see him were off the scale: Paul Newman! Gene Hackman! It was phenomenal – that’s how well-regarded he was. But of course people like that wanted to breathe in what he did. You can’t fight or hide a real gift, just as you can’t fail to recognise and respect it. It has nothing to do with whether you have five Oscars under your belt; it transcends any of the nonsense.

I’ll always remember one night early on. I was super-nervous; I was just starting out and it was such a big deal for me. The two of us made our entrance together and he took both my hands and looked me in the eye and said: “Let’s just go out there tonight and pray.” That was the coolest thing. It was also poetic – and that’s who he was. I loved him very much.

As told to Catherine Shoard

I committed what in the theatre is considered a cardinal sin

Ken Stott

I was barely a month out of drama school in 1973 when I saw Ian Holm at the Royal Court as Hatch in Edward Bond’s The Sea. The truth, the power, the intensity, shocked me – and inspired me.

Three years later, I was carrying a spear on behalf of the RSC on a world tour when the news came in like a chill wind through my soul. Ian Holm had suffered “stage fright”. Not the kind that makes you a wee bit more nervous than you normally are in front of an audience and a “scrotum of critics”, but the kind of hellish incident that can end your fucking career.

Details were scant; we, the young actors who didn’t know him but unanimously adored him were “shielded from” the information. Apparently it had happened during the final preview of The Iceman Cometh, at the Aldwych. Someone said they knew someone who’d seen it and “it was going to be the best work he’d ever done so why should he be afraid?” Yes, so why be afraid we asked, but we all of us knew, and we were all afraid.

A year or so later, I got my first substantial role, in Kennedy’s Children directed by the great David Scase at the Library Theatre Manchester. One evening as I was preparing for our final preview, my colleague Maggie Ollerenshaw announced brightly, indeed almost matter-of-factly, that Ian Holm would be in the audience, and would I like to meet him afterwards? I was a wreck. We met in the bar afterwards where Ian spoke encouragingly about the production and during a slight lull in the conversation I committed what in the theatre is considered a cardinal sin, blurting out: “You are my favourite actor in the world.”

There followed a terrible silence during which David smiled into the middle distance and Maggie gave me a withering look. Ian stared at me … then suddenly threw his arms around me and said: “Thank you.”

It was 20 years before we met again, and I was enjoying a run of Art at Wyndham’s theatre. As I walked into the Ivy one evening after the show I saw Ian in the lobby. I approached him and tentatively offered my hand, he grasped it, pulled me to him, threw his arm around me and said: “You are my favourite actor.”

Latterly, despite the onset of illness, he came to see my work and he was very supportive. Despite the astonishing variety and brilliance of his work in film, if I were to re-evaluate his work I’d need look no farther than the Royal Court to see that his truth stands against the demonstration of acting and his power and intensity against attitude.

Laurence Olivier came up to him and said: ‘How do you do it?’

Hugh Hudson

I first met Ian when I was preparing Chariots of Fire and he fitted the part of the running coach perfectly. I put him in my second film, Greystoke, too, and would have loved to put him in every film I made but it never quite worked out, and then he died. We had a plan quite recently for a film in which he’d play someone with Parkinson’s. A great shame, as he was up for it. He wanted to work. He loved to be performing.

Ian was the consummate supporting actor. He never wanted to lead, but he was so good he’d somehow end up becoming the lead anyway. His humanity and depth spilt over into the whole story.

Both Ian’s roles for me were as mentors, and he was a man you’d very readily learn from. I remember being in tears watching him shoot the scene in which he shows Tarzan how to use a razor – he turned the words into something comic and magical and extremely moving. He taught me so much, particularly about working with other actors, which is with enormous discretion and patience.

Ian’s great innate wisdom and honesty gave him immediate access to the truth of any character. That gentle understanding was behind his magnetism, I think. Someone told me that Laurence Olivier once came up to him and said: “How do you do it?” Ian had these amazing little inflections, incidental bits of performance genius. It’s striking an actor like Olivier, the opposite of Ian in style, was so impressed.

They were both such powerful actors in their own ways – not that Ian, too, couldn’t be steely and terrifying when he wished. I thought the RSC’s current artistic director, Gregory Doran, described him perfectly when he said Ian “was entirely original. Entirely a one-off. He had a simmering cool, a compressed volcanic sense of ferocity, of danger, a pressure-cooker actor, a rare and magnificent talent.”

I think Ian and I were drawn to one another because neither of us liked to speak much. I was completely at ease with him; we never had a problem with one another. He was such a modest and unshowy man. His sense of character was always impeccable and we simply understood one another and trusted each other entirely. We’d communicate on set with our hands and eyes, but he immediately knew what I wanted, which I haven’t known before or since with an actor.

We saw each other socially a lot, and had a particularly memorable time at a film festival in Nimes in 2007 where our two films together were shown. In London, we’d go to restaurants and drink champagne, which he loved, and called “shampoo”.

He was an adorable, adorable man and could be terribly funny. He and his wife and son came for Christmas one year – we both had weddings around the same time. Sophie and he were married for 20 years and she nursed him for 12 of those and gave him a good and happy life.

They always had fun together. It was always such a laugh being with them, even if, later on, you could only see that in his sparkling eyes. It’s so sad such a beautiful spirit has gone.

As told to Catherine Shoard

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies