Explore mid-century textile designer Lucienne Day’s love of mustard yellow

If you were looking for a single quality to define the career of Lucienne Day, self-belief might well be the one you would choose. What else could have compelled her to stand firm behind ‘Calyx’, a textile design she submitted to Heal’s to be displayed at the Festival of Britain in 1951?

‘Calyx’ was... different.

True, the festival was supposed to usher in a fresh, forward-looking mood after the grim mire of the war years. A ‘tonic for the nation’, as one politician put it. And true, her design – abstract, irregular forms resembling flower heads on slender stems – evoked the work of contemporary artists like Joan Miró and Alexander Calder. But Tom Worthington, Heal’s design director, was not a fan. She persisted and he relented – but would only pay half the usual 20-guinea fee.

As would happen again and again over the following years, Day’s self-belief paid off and the design became an award-winning bestseller. (Worthington not only later paid her the remaining 10 guineas, but would go on to commission her again and again. Over 20 years, she designed more than 70 patterns for Heal’s)

Born in Coulsdon, Surrey, in 1917, Day spent her life creating confident, bold designs, principally in interiors textiles. In contrast to the stuffy chintzes and heavy arabesques of the pre-war years, she favoured abstract, modern patterns. An early print featured a characterful line drawing of a horse’s head. Later on, she became more abstract and geometric: her work following and even pushing the boundaries of visual design.

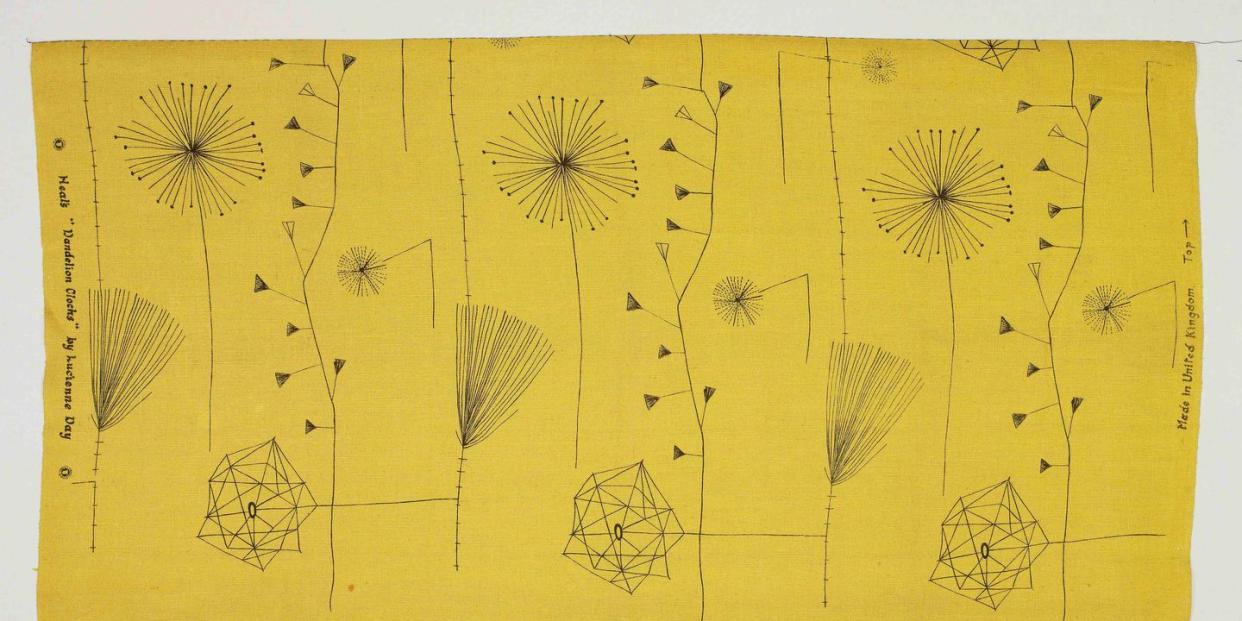

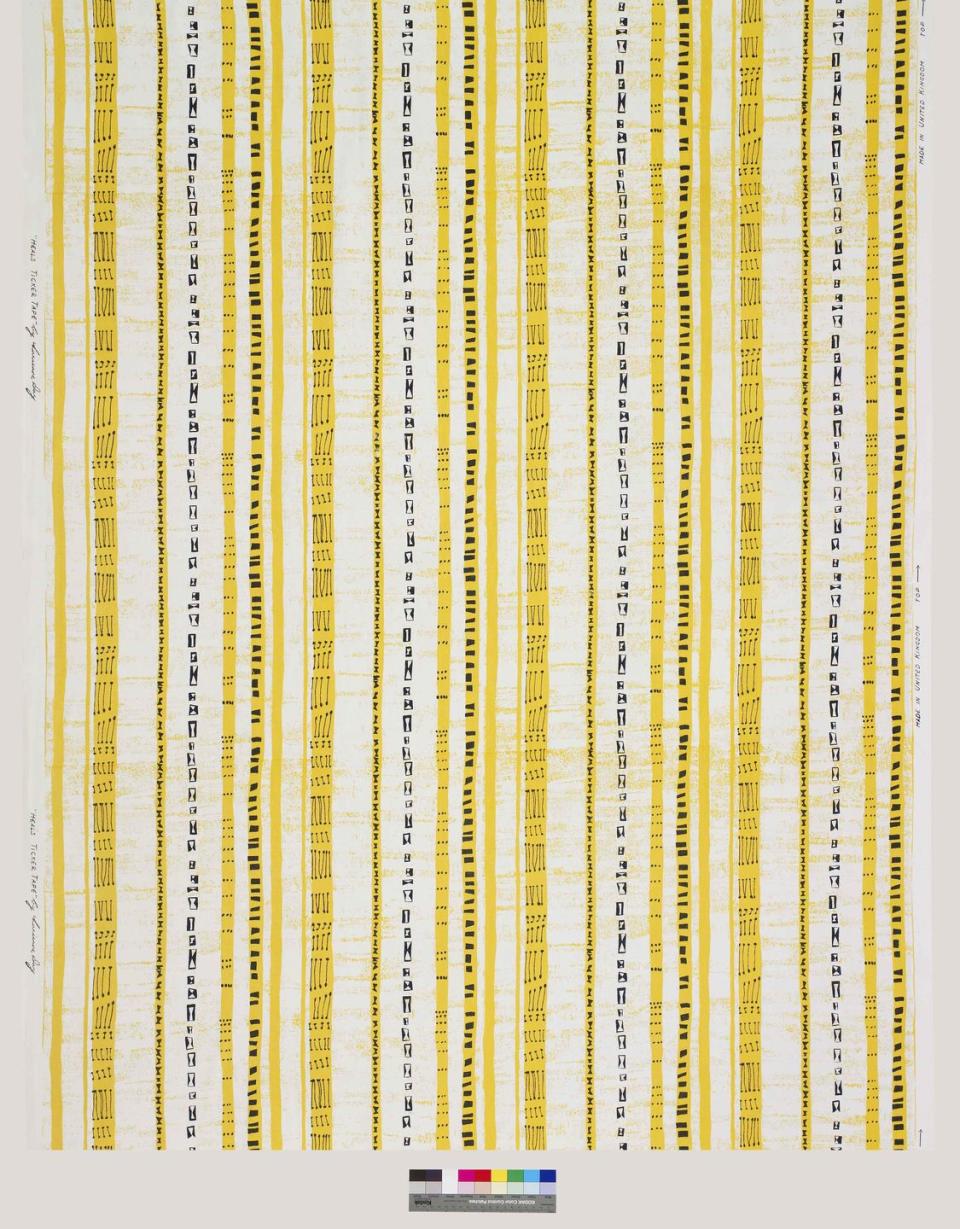

Her chosen palette reflected her personality. She enjoyed bold shades: teals, olives, browns, chartreuse, twilight violets and, of course, mustard. This latter hue, which had packed such a punch in ‘Calyx’, returned in the whimsical ‘Dandelion Clocks’ (1953) and in geometric splendour in ‘Isosceles’ (1955). These textiles, true to the original mission of the Festival of Britain, evoked the new and optimistic mood of the mid-century.

More incredible still, many were affordable enough to enter the homes of people who had never been able to access contemporary design before. If buying whole curtains was too much, people could get tea towels instead, such as the mole-mustard-turquoise ‘Bouquet Garni’ (1959) or the rather romantic ‘Night and Day’ (1961), featuring an acid-bright sun and a star-and-owl moon.

Self-belief allowed her to decorate the Chelsea home she shared with her husband, furniture designer Robin Day, with a confident good taste. And although their careers complemented each other and they often worked together, she was a star in her own firmament. Perhaps that is why, like botanical forms, heavenly bodies were recurring motifs. One of her very last pieces, ‘Aspects of the Sun’ (1990), is a silken masterpiece: an ode to form and colour, especially, of course, sinus-stinging yellow.

This article first appeared in ELLE Decoration November 2020

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.

Keep your spirits up and subscribe to ELLE Decoration here, so our magazine is delivered direct to your door.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies