Fires, Crashes, and Fascism: The Crazy Story Behind the Making of 1925′s ‘Ben-Hur’

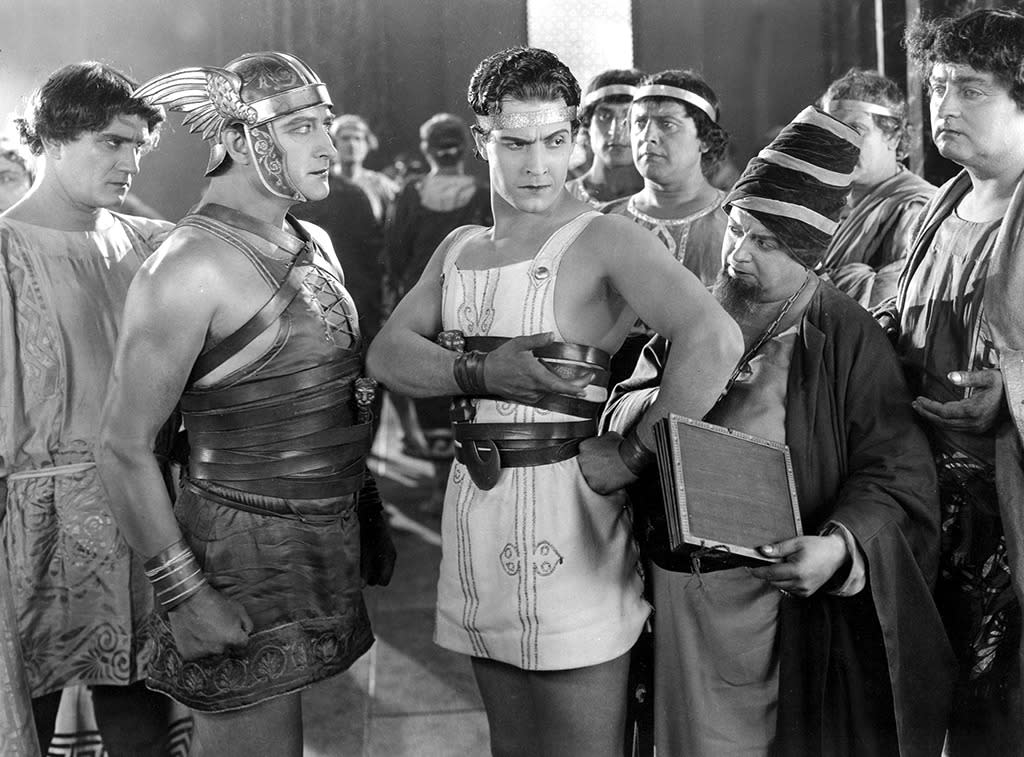

Francis X. Bushman and Ramon Novarro in Ben-Hur. (Photo: Everett Collection)

The 1959 epic Ben-Hur is one of the biggest films in Hollywood history, so it makes sense that it has generated its share of outsized urban legends: A stuntman’s actual death can be seen in the film; a red Ferrari zooms through one frame of the chariot race; a screenwriter added a gay romance without star Charlton Heston’s knowledge. Of those rumors, only the last appears to be true (read more about it here). But none of these legends are as crazy as what actually happened on the set of the original Ben-Hur, a wildly expensive and unsafe 1925 production that killed at least one cast member and more than a hundred horses. In the end, the studio didn’t care because the adaptation of the 1880 Lew Wallace novel about ancient Rome was a hit. With the third Ben-Hur feature film opening in theaters today (that’s not counting the one-reel short from 1907), let’s look back at the mind-boggling events that made the first one possible.

The story of the original Ben-Hur — which also includes fire, floods, fascism, and looting — was recorded by film historian Kevin Brownlow in his 1968 book The Parade’s Gone By, a chronicle of Hollywood’s silent era based on extensive interviews with people who were there. From the beginning, producers of the ancient Roman epic seemed to be in over their heads: Months of largely unsupervised shooting in Italy in 1923 yielded terrible footage, prompting the studio to fire the director and most of the stars and start over from scratch.

Watch scenes from the original Ben-Hur in this excerpt from the 1980 documentary series Hollywood, directed by film historian Kevin Brownlow:

Under replacement director Fred Niblo, filming resumed in Rome, which had been under the control of Mussolini’s National Fascist Party for about a year. Political tensions leaked onto the set during the filming of the first big action sequence, a sea fight between a Roman war galley and a pirate ship (both life-sized, seaworthy boats built especially to be destroyed for the film.) The casting director hired dozens of Italian peasants to play the ships’ crews, and decided to add some realism to the conflict by placing the fascist extras in one crew and the anti-fascist extras in another. Niblo intervened, which is when he discovered that the ships were equipped with real, sharpened swords. The weapons were removed from set before anyone could be stabbed.

Nevertheless, things got gory. At the climax of the scene, the Roman ship was supposed to catch fire. While Niblo was shooting the effect, a wind fanned the flames and caused the fire to spread rapidly. The extras began leaping overboard. Some were wearing heavy armor; many couldn’t swim. Francis X. Bushman, one of the film’s stars, said that he pleaded with the director to help the drowning men, to which Niblo replied, “I can’t help it! Those ships cost me $40,000 apiece.” Three extras were recorded as missing after the scene was filmed. Some production members claim that either two or three men re-appeared days later, having been rescued by a fishing boat; others are certain they drowned. In Brownlow’s chilling words, “Opinions differ as to the casualty rate.”

Bushman and Novarro (Photo: Everett Collection)

If those men did survive, then the sea-battle catastrophe was the second-worst thing to happen during Ben-Hur. Before we get to the actual worst thing, here are some of the runners-up: An elderly actor nearly caught pneumonia when forced to shoot on a raft in the Mediterranean Sea for three days. Fred Niblo got angry and threw stuff at child extras. Set construction had to wait because of political riots. The props were destroyed in a warehouse fire. And finally, crew members accidentally dug into an ancient Roman catacomb, destroying the site and enabling a free-for-all pillage of 2,000-year-old artifacts.

Which brings us to the chariot race. Filming for the big action sequence — the centerpiece of all Ben-Hur adaptations — began in Italy on a custom-built Coliseum set, under the guidance of second-unit director B. Reeves Eason. The set looked real, but the surface of the track hadn’t been adequately prepared to handle horses and chariots. After a few laps, ruts formed in the ground, with deadly consequences. “During one take, we went around the curve and the wheel broke on the other fellow’s chariot,” said Bushman, who played Ben-Hur’s rival charioteer Messala. “The hub hit the ground and the guy shot up in the air about 30 feet. … It was like a slow-motion film. He fell on a pile of lumber and died of internal injuries.”

Dozens of horses were also killed, either during chariot crashes (one of which nearly took out the film’s leading man, Ramon Novarro) or because Eason ordered them to be shot. “They never had a vet attend any horse,” Bushman told Brownlow. “The moment it limped, they shot it.” The equine death toll was estimated at about a hundred.

A trailer for the first, silent Ben-Hur:

After all that, the footage from the Roman chariot race turned out to be unusable, because the outdoor location had too many shadows. The whole sequence was reshot on a Culver City soundstage months later by 42 cameramen and 30 assistants hidden strategically around the set. (One of those assistants was a young William Wyler, who would go on to direct the 1959 Ben-Hur.) This time, things went more smoothly — until the scene’s climactic chariot crash, when two chariots inadvertently became tangled and a pile-up ensued. At least five horses were killed, and things got so hairy that assistant director Henry Hathaway ran into the arena to try and stop the oncoming drivers. As seen in Brownlow’s 1980 documentary series Hollywood (above), Hathaway’s accidental cameo made the final cut.

Also in the final cut: extras jumping overboard from the flaming ship and horses being crushed by chariots. All of those dangerous moments helped created the larger-than-life movie that thrilled audiences in the 1920s. Ben-Hur was enough of a hit to nearly justify its $3.9 million budget, by far the largest of any silent-era film, and moviegoers had no idea how hazardous those action sequences actually were. (For curious modern-day viewers, the film is currently available to stream on multiple sites, including YouTube, under the title Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.)

The directors of subsequent Ben-Hurs made sure not to repeat the silent film’s mistakes. The breakneck chariot scene in 1959 was actually assembled with great caution by Wyler’s second-unit director, legendary stuntman Yakima Canutt. That rumors of stuntman and horse deaths in the Heston film persist to this day is a testament to just how notorious that original 1925 production became. For the 2016 remake, director Timur Bekmanbetov had the benefit of CGI — though he boasted to Business Insider that his scene was shot mainly in-camera, including actual chariots pulled by 90 horses on a thousand-foot-long set. “You really feel you’re in that chariot driving it,” the director said. Judging from how things went on the first Ben-Hur, though, we’re all better off on the sidelines.

Watch a clip from the chariot race of the new Ben-Hur:

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies