Honey Boy review: Shia LaBeouf offers a dose of pure cinematic therapy

Dir: Alma Har’el. Cast: Shia LaBeouf, Lucas Hedges, Noah Jupe, Byron Bowers, Laura San Giacomo, FKA Twigs. 15 cert, 94 mins.

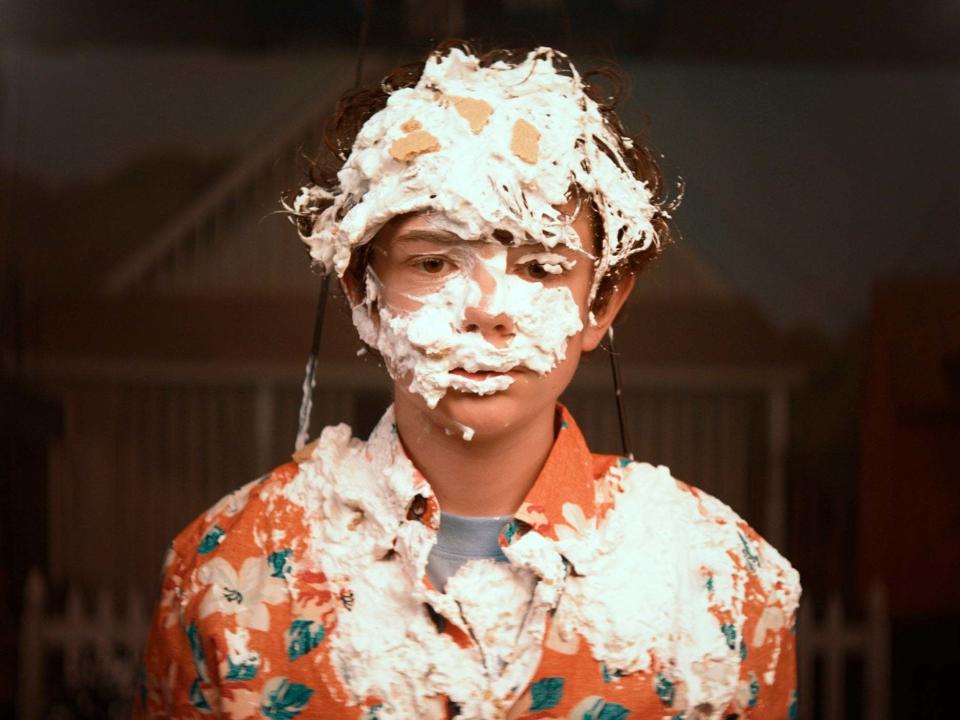

“I’m gonna make a movie about you,” Otis Lort (Lucas Hedges) tells his father in Honey Boy’s final moments. Shia LaBeouf may have changed the names and muddied the details, but his script can only run from the truth for so long – this is a cinematic therapy session. The actor first wrote the film back in 2017, during a stint of court-ordered rehab. He plays his own father (here named James), while he enlists Noah Jupe and Lucas Hedges to stand in as his younger self (Otis) at the ages of 12 and 22 respectively. It’s a psychologist’s dream.

Yet, despite this, Honey Boy never lapses into self-pity. In the hands of director Alma Har’el, previously known for her documentary work, the film delicately bears its scars and finds peace by acknowledging how childhood pains can make and break us. We open on the older Otis, who looks into the camera and utters a few helpless cries, before he’s thrown into the air like a piece of litter caught up in a gust of wind. It’s all for show, since he’s on the set of one of his big-budget action films (a clear nod to the Transformers movies). We then see the same stunt repeated with his younger self, then a child star. Trauma has frozen his emotional state; his life feels as outside of his control then as it does now.

A montage, furiously cut together by editors Dominic LaPerriere and Monica Salazar, condenses the familiar parts of the story: addiction, rage, and being on the wrong side of the law. Otis ends up in a rehab facility, where the staff and fellow patients (including roommate Percy, played by Byron Bowers) react to his outbursts and petulance with saintly patience. At first, he rejects his PTSD diagnosis. He struggles to separate his father’s abuse from his love. James can be violent, but most of the damage done is more insipid in nature – it’s in the way he moulds Otis’s image of himself, for example.

Much of the film is spent with Otis and James, alone in their dreary San Fernando Valley motel room. Cinematographer Natasha Braier lights nighttime interiors with a sickly neon that seeps through the curtains and into every corner of the room – a personal hell. Here, the pair of them shift through an ugly, messy stew of emotions. They rage and they weep. They beg for the other’s approval. They strive desperately to assert control over the situation. Jupe tackles the complex material with ease, particularly when he’s forced to relay over the phone an argument between his parents, mimicking each side’s anger and hurt.

With his receding hairline and southern drawl, it’s impossible to know how accurate an impression LaBeouf is doing of his father (if it’s an impression of all). Yet it’s a performance that stills feels startlingly intimate. Who knows what sense of healing Honey Boy may have brought the actor, but its raw humanity serves as a balm, too, for our own wounds – in whatever form they may take.

‘Honey Boy’ is released in UK cinemas on 6 December

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies