How Honor Blackman in 'The Avengers' changed women on TV forever

For most people, Honor Blackman will forever be known as the woman literally having a roll in the hay with Sean Connery as Bond Girl Pussy Galore in Goldfinger.

And if you’re of a certain vintage, you might remember her as the sassy, saucy grandmother in cheesy early 90s sitcom The Upper Hand.

But the part of her legacy that’s become somewhat obscured in the intervening 60 years is perhaps her most important.

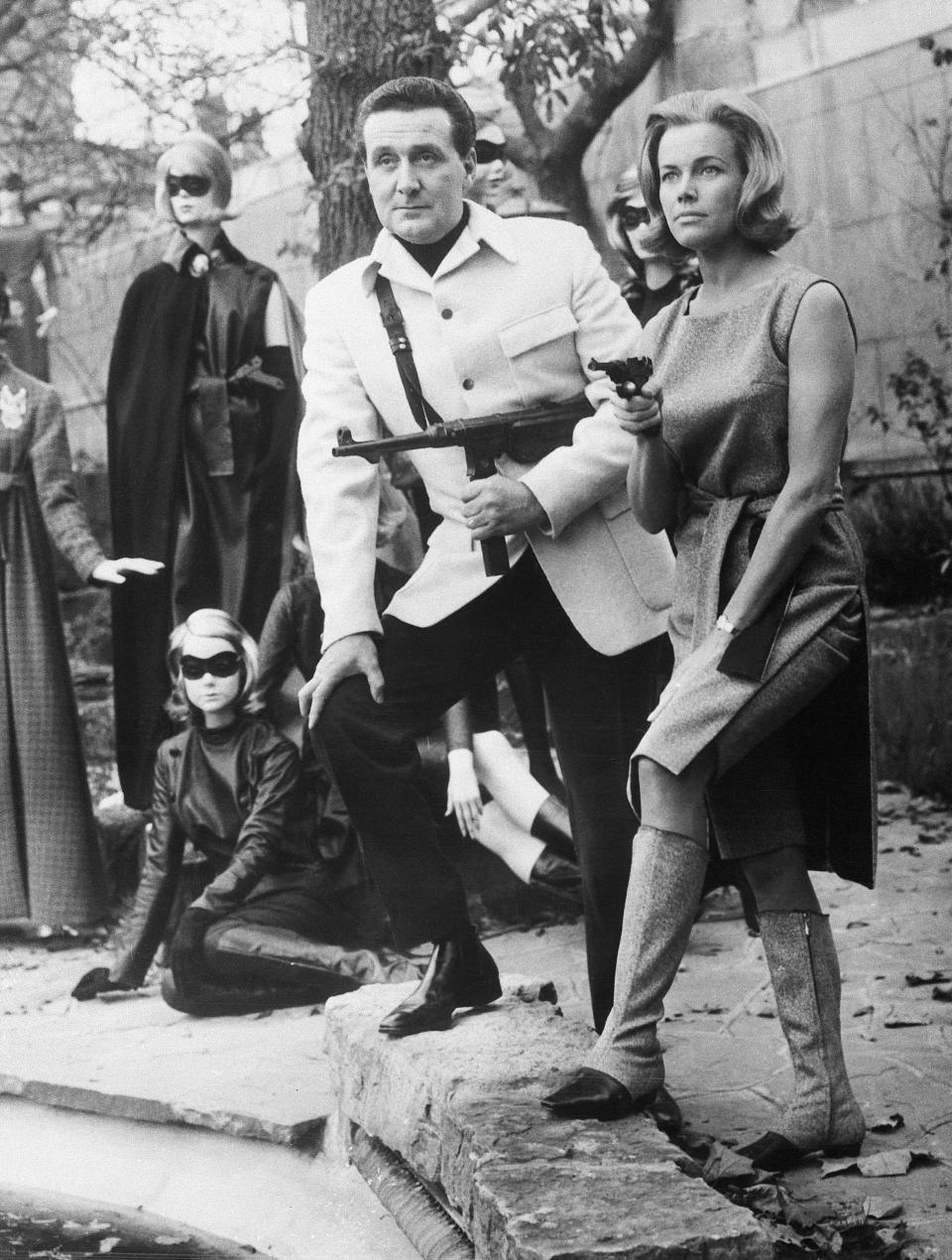

While Diana Rigg remains iconic as the leather-clad Emma Peel in idiosyncratic 1960s spy show The Avengers, she wasn’t actually the first of John Steed’s (Patrick MacNee) female sidekicks.

Mrs Cathy Gale was: arriving in the second season and played by Blackman, who recently died aged 94. She was inspired by two famous Margarets – legendary anthropologist Margaret Mead and US war photographer Margaret Bourke-White.

Producer Sydney Newman combined their attributes with a startling image he’d seen on TV of a British woman whose family had been murdered by the Mau Maus in Kenya. She’d appeared on the news with her baby in a backpack, brandishing a gun and an ammunition belt. It convinced Newman that Steed could have a female partner (MacNee had actually been the sidekick in the first season, supporting lead actor Ian Hendry who then decided to leave to pursue a movie career).

Read more: How Honor Blackman set the Bond girl template

“They saw the coming of the new professional woman,” says Professor Toby Miller, author of The Avengers, a book about the show. “They also wanted to reach out to female audiences. This was ITV, it was the only commercial station and they were interested in selling things to couples and women.”

By the time she got the role of Cathy, Blackman was already in her mid-30s and had been a contract player at the Rank Film Organisation. She wasn’t the producers’ first choice, they erred towards Nyree Dawn Porter or Fenella Fielding. But the fact she wasn’t a naïve ingenue played in her favour – Cathy was intended to be very athletic, very resourceful and very self-possessed.

To make her feel authentic, the programme-makers enlisted two women, ITV press officer Marie Donaldson and writer Doreen Montgomery, to add nuance and bring a female perspective to the character.

Blackman’s first episode was shot at Teddington Studios in June 1962. To say those early seasons, which were in black and white, were rough around the edges would be an understatement.

“They were conditions for making television that people couldn’t even imagine today,” says Toby Miller. “You’re looking at things that were mostly shot on video, very grainy and barely edited. There are even scenes where they fall over things or apologise, it’s like live television.”

Indeed, Blackman’s first instalment took just an hour to shoot.

Some of that is why Cathy and Blackman never achieved the same legacy as Diana Rigg’s time on the show.

“All of that persona of Emma Peel that Diana Rigg incarnated so wonderfully was in fact in place with Honor Blackman,” says Miller. “But because the production values were low compared to the seasons with Rigg, Blackman is a bit lost in the mythology.”

Still, Cathy Gale was a hit, representing the kind of femininity that women across the U.K. wanted for themselves. In fact, she made such a popular impact that the other female character she was going to alternate with, a singer called Venus Smith played by Julie Stevens, was reduced to just six appearances in the 26-episode second season before being ditched altogether.

“People wrote about her a lot in the newspapers, they talked about the new woman,’ says Professor Miller. She, alongside MacNee, won a best independent television personality of the year award from the Variety Club of Great Britain, mingling with fellow guests like The Beatles.

“There’s no doubt that she was a vanguard in terms of representing what had not yet come into being as a social movement. This was one of those occasions where something is set up as a possibility by what you see on-screen that isn’t yet there in the social world. In 1963, you’re getting the publication of The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan and the first stirrings, certainly amongst the left, of second wave feminism.”

Blackman herself wasn’t afraid to speak up either. “Prior to the 1964 election, The Avengers’ episode was postponed because she had shot a campaign advertisement for Liberal Party,” says Miller. “She was quite significantly involved in talking about women’s issues.”

She was also an early fighter for equal pay. Before the third season, ITV (then called ABC) thought about dropping her when she and MacNee both asked for a pay rise. It was suggested that Blackman make way for someone cheaper, but according to Michael Richardson’s Bowler Hats and Kinky Boots, ABC executive Howard Thomas recognised how vital she was to the franchise and signed off on the extra money.

Read more: Honor Blackman on Goldfinger

Elsewhere in popular culture, Cathy’s look was also making a splash. Blackman wore a wig because her fine blonde hair didn’t sit correctly on-camera, but it was her so-called ‘kinky boots’ and leather outfit – a fabric that became synonymous with Diana Rigg/Emma Peel – which really caused a stir.

“Honor Blackman told great stories that, because everything was in black and white, she was actually wearing green leather rather than black,” says Professor Miller. “And because of all the studio lights, during the action sequences people smelled a bit by the end of an episode!”

Her two-piece suit was originally going to be suede, but that didn’t work for the lighting setup. In the media, it was trumpeted that Cathy’s clothes were being made by top 60s fashion designers like Frederick Starke and Michael Whittaker, but there is a suggestion this was more of a marketing ploy and that ABC’s wardrobe experts, Audrey Riddle and Ambren Garland were actually the masterminds behind the outfits. Either way, it became vital to the strength of the character and was influential, even if Rigg’s black catsuit subsequently became more famous.

When Blackman finally left the series in 1964 to take up a five-film contract with Bond producer Cubby Broccoli, there’s no doubt she had changed the television landscape. A year later, Swinging London really kicked into gear, along with the kinds of bold looks Blackman had pioneered. Meanwhile in America, Cathy Gale-esque characters like private investigator Honey West started to appear on TV.

Gale and Steed’s partnership, which was flirty but equal, had also forged new ground for police procedurals and on-screen male/female relationships. “These shows in the 50s and 60s provided no space of the private life of the detectives, who are all men,” explains Miller. “In The Avengers, there’s no distinction between the private and the public. They don’t have an office they go to, they don’t have – apart from in the very early episodes – a hierarchy they report to on a routine basis. You see their living circumstances, but there are no boyfriends, girlfriends, husbands, wives and that’s what’s so interesting about it. It breaks of the rules of the conventional cop show of that time.”

And while you never definitively find out if they sleep together, their banter suggested something was stirring outside the ‘normal’ family unit as the only place for lovemaking, still a transgressive idea at the time.

After The Avengers, Blackman went on to further success, but, says Toby Miller, “There’s no doubt that her role as Cathy Gale had such a big impact on the world of the popular that she got stereotyped even before Goldfinger happened.”

Nevertheless, Blackman as Cathy remains an underappreciated pioneer.

“She always exhibited pride in what she’d done and talked very movingly about the equal relationship she’d had on-screen with the John Steed character,” says Miller.

With her recent death, it’s fitting to remember what that has meant for subsequent generations of actresses and the characters they play.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies