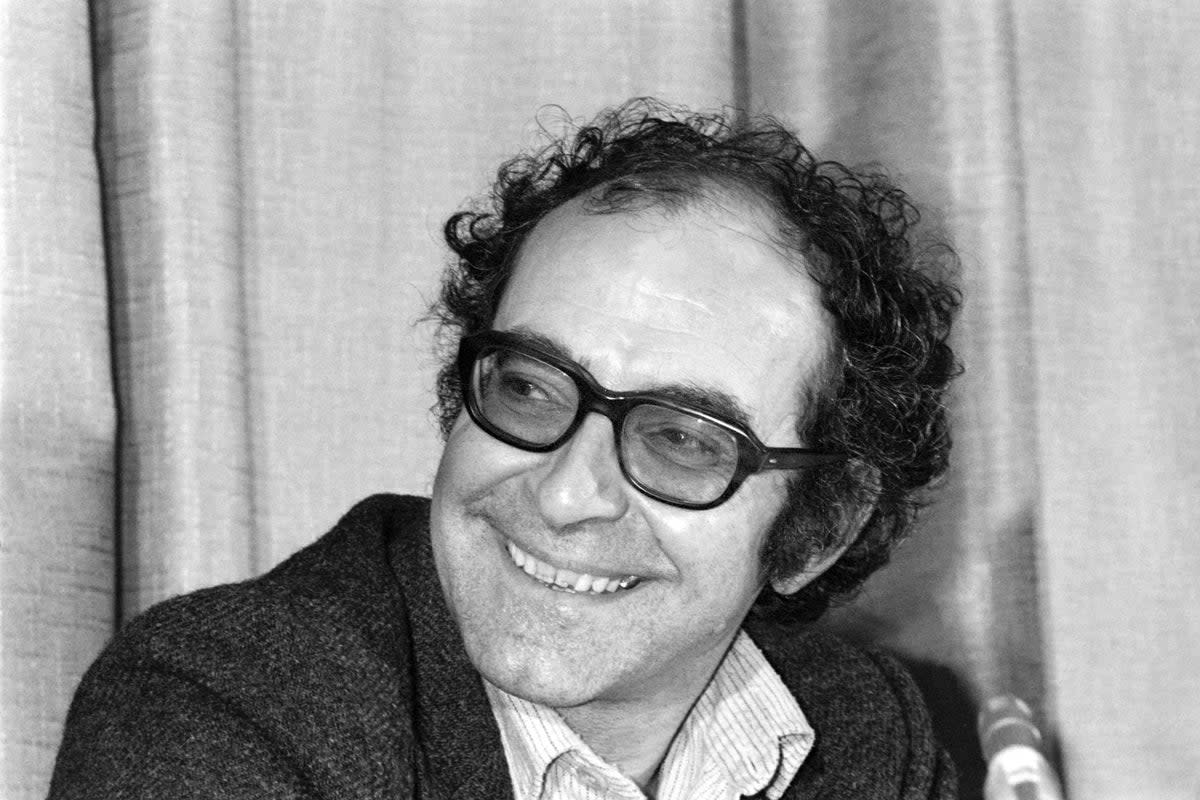

Jean-Luc Godard death: From Breathless to Contempt, his most famous and important works

In a blow for cineastes everywhere, Jean-Luc Godard has died aged 91. The film director is one of cinema’s most influential figures: he was a pioneer of the revolutionary French Nouvelle Vague, creating a barrel of radical and political films in the Sixities.

Known for his experimental filming style, Godard was voracious in his craft, producing as many as 32 features and medium-length films, more than 50 short films, and 15 films as part of the political filmmaking group The Dziga Vertov Group, which he founded alongside Jean-Pierre Gorin.

French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted his condolences, saying: “Jean-Luc Godard, the most iconoclastic of the New Wave filmmakers, invented art that was resolutely modern, intensely free. We are losing a national treasure, the perspective of a genius.”

Ce fut comme une apparition dans le cinéma français. Puis il en devint un maître. Jean-Luc Godard, le plus iconoclaste des cinéastes de la Nouvelle Vague, avait inventé un art résolument moderne, intensément libre. Nous perdons un trésor national, un regard de génie. pic.twitter.com/bQneeqp8on

— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) September 13, 2022

Godard was born in Paris in 1930, grew up in Nyon in Switzerland, and moved back to Paris after his studies. He found a home in the city’s cine-clubs, where he started both writing about and making films. His earliest works were a series of shorts, including the 1957 Charlotte and Véronique, or All the Boys Are Named Patrick.

Then, he only picked up pace: between 1960 and 1967 he made 15 pictures, half of which, at least, remain some of cinema’s most important films: think Breathless, Contempt, Masculin Féminin.

In the late Seventies and Eighties his political ideas didn’t sustain their momentum, but no matter: Godard’s influence continued. His 2010 film Film Socialisme (which reignited accusations of antisemitism against the director) won an honorary Oscar, his 2014 film Goodbye to Language won the Jury Prize at Cannes that year, and his Image Book was selected to compete for the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2018.

Throughout his life, Godard remained a theorist and critic. He was “a radical who was the first filmmaker in the medium’s short history seriously to think about what cinema was and what it meant,” wrote The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw.

If you’re new to Godard, or have wanted to see some of his films but don’t know where to start, here is our round-up of his best or most important works to watch now.

Breathless / À Bout De Souffle (1960)

Jean-Luc Godard’s first feature remains one of his most important films. It’s a crime drama about criminal Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and his girlfriend Patricia (Jean Seberg). Michel is obsessed with Humphrey Bogart and models himself on the Hollywood star’s on-screen persona. He’s penniless and on the run; he meets Patricia. It’s all drama drama, which is only made more thrilling by the original filming style.

The film marked a major breakthrough for both Godard and Belmondo, catapulting both to fame. To this day Breathless is considered one of the best films ever made.

Pierrot Le Fou (1965)

Described as “bafflingly wild, almost incoherent” by The Guardian, Pierrot Le Fou stars Belmondo again alongside Anna Karina (Godard’s future wife). It’s based on Lionel White’s 1962 novel Obsession and tells the story of an unhappily married man trying to escape his boring society life. He takes a trip from Paris to the Mediterranean with a girl who is being chased by hitmen.

Once again, it’s a cinematic marvel: characters break the Fourth Wall, looking at the camera; there are edits that have been obviously inspired by the pop art movement and it includes sudden cuts to mass culture moments.

Masculin, Féminin (1966)

Masculin, Féminin tells the story of Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud) who chases budding popstar Madeleine (Chantal Goya). The two start seeing each other and then start a ménage à quatre with Madeleine’s roommates (played by Marlène Jobert and Catherine-Isabelle Duport).

Then there’s an interview sequence running through the film, where the actors are asked about love, sex and politics, and then these scenes are cut with various other spin-off plots. A total classic.

Alphaville (1965)

Alphaville evades easy categorisation – is it a dystopian science fiction film? A film noir? It’s set in the future, and is about Government agent Lemmy Caution (played by Eddie Constantine) who is sent on a mission to Alphaville to chase rogue agent Henri Dickson (Akim Tamiroff) and a despotic scientist.

There’s mind-control in the mix and of course, a gorgeous babe Natacha (played by Anna Karina) on board to help him.

Contempt / Le Mépris (1963)

Starring Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, and Giorgia Moll, and based on the 1954 novel A Ghost at Noon by Alberto Moravia, Contempt is about unhappy producer Jeremy Prokosch, who hires Fritz Lang (incredibly, played by the director himself) to direct a new version of The Odyssey.

Lang isn’t doing a great job, and so a screenwriter is brought in to try and save matters. But then things get messy when the screenwriter and his wife (played by Bardot) start fighting.

Considered one of Godard’s greatest works, it continues to make “greatest films” lists, including Sight & Sound magazine’s 2012 100 greatest films of all time list and BBC’s 2018 list of the 100 greatest foreign-language films.

Weekend / Week-End (1967)

Weekend is a black comedy about a bourgeois couple who both have secret lovers and who are both conspiring to kill each other. The perfect premise for a fantastic French thriller.

Then imagine model-turned-actress Mireille Darc and actor and director Jean Yanne starring as the couple, that Godard is behind the camera, and that the plot goes on to include a country house, a dying father, inheritance, car accidents and vignettes of literary figures including Emily Brontë. In true Godard form, it’s quite mad. All we know is that it’s worth a watch.

Goodbye to Language / Adieu Au Langage (2014)

Years later, Godard hadn’t lost his sense of humour, or verve for including all of cinema’s latest trends in his films as part of the discourse of the film itself: in Goodbye to Language he used 3D to enhance his experimental narrative essay about a two versions of a love affair.

The two versions are called “1 Nature” and “2 Metaphor” and the film flits between the two. Showing his lasting power and relevance, the film became one of the most acclaimed of the year, being celebrated by Cahiers du cinéma and the BFI, to name a few fans.

Godard hand wrote a synopsis in prose, which was shared on Twitter:

“The idea is simple / A married woman and a single man meet / They love, they argue, fists fly / A dog strays between town and country / The seasons pass / The man and woman meet again / The dog finds itself between them / The other is in one, / the one is in the other / and they are three / The former husband shatters everything / A second film begins: / the same as the first, / and yet not / From the human race we pass to metaphor / This ends in barking / and a baby’s cries / In the meantime, we will have seen people talking of the demise of the dollar, of truth in mathematics and of the death of a robin.”

Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1988-1998)

This gigantic eight-part video documentary project is not exactly something you can sit down and watch on a Sunday night. However, it’s largely viewed as one of Godard’s best and most moving works.

He investigates cinema in all its forms – its history, its conception and production. He looks at how cinema has changed the 20th century and how the 20th century changed cinema. And what could be a greater gift to cinephiles than this ode to cinema-making from one of history’s greatest contributors?

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies