Jim Steinman, master of the power ballad, gave pop an operatic energy

In 1989, the NME interviewed Jim Steinman. The late journalist Steven Wells found him on fine, very Jim Steinman-ish form. He was presiding over a video shoot for a single by his new project Pandora’s Box, directed by Ken Russell, a man who shared Steinman’s zero-tolerance policy towards subtlety and good taste. Amid Russell’s exploding motorbikes, white horses surrounded by fire, and S&M gear-clad dancers gyrating on top of a tomb, Steinman offered his thoughts on current rock (U2 were “the most boring group in the world”) and dished scandalous gossip about the artists he’d worked with. He also announced that the Pandora’s Box album had been inspired by a scene in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights where Heathcliffe exhumed Cathy’s corpse and “danced with it on the beach in the cold moonlight”. It should be added that this scene seems to have existed entirely in Steinman’s head – nothing like it happens in Brontë’s book. But then, Jim Steinman seemed very much the kind of guy who might read Wuthering Heights and decide it needed amping up a little.

He also ruminated on his own position within rock music. “It’s always struck me as weird that a lot of people in rock’n’roll think my stuff is ridiculous,” he said. “I think that so much rock’n’roll is confessional. It’s like black and white film. That’s what a lot of people think rock’n’roll should be … I just see it as fantasy, operatic, hallucinations, stuff like that … I kinda think rock’n’roll is silly, in the best way. The silly things are kinda the things that are alright.”

Related: Jim Steinman, hitmaker for Meat Loaf and Celine Dion, dies at 73

This was the philosophy behind Steinman’s extraordinary, more-is-more approach to rock music – first revealed on Meat Loaf’s 50m-selling 1977 debut album Bat Out of Hell and sustained until his death, selling millions more courtesy of Steinman-helmed releases by everyone from Céline Dion to the Sisters of Mercy. Along the way, he helped invent the power ballad, though it’s worth noting that most big 80s power ballads were essentially a toned-down version of Steinman’s writing style. Not even the 3am drunk-dialling insanity of Heart’s Alone was as piquantly grandiloquent as Meat Loaf’s For Crying Out Loud or Bonnie Tyler’s Total Eclipse of the Heart, the latter featuring an instrumental interlude punctuated by explosions that, in the song’s initial incarnation, were supposed to represent nuclear bombs being dropped.

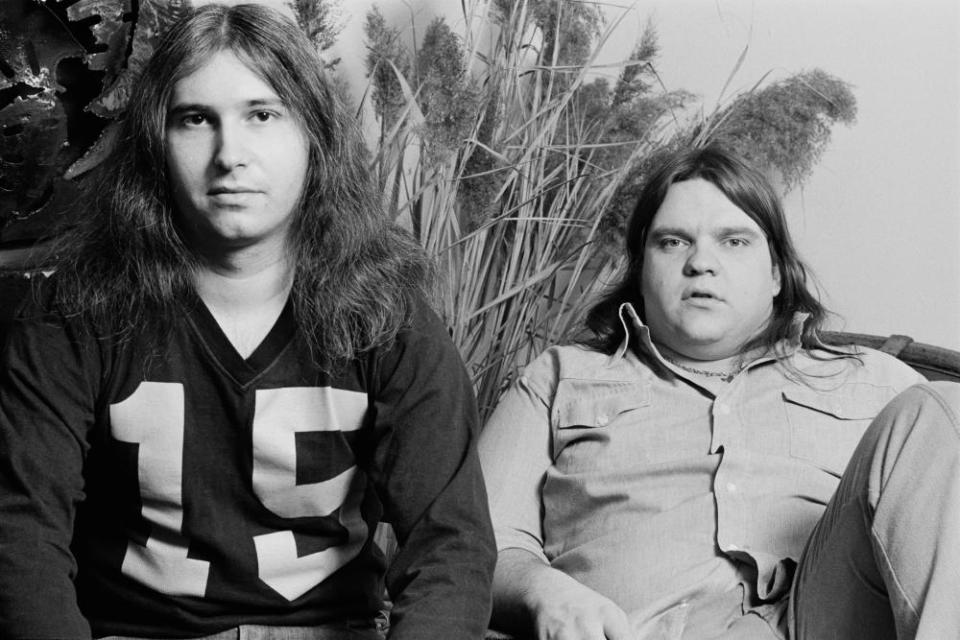

He had begun his career in musical theatre, which clearly remained an abiding passion throughout his life, as he occasionally repurposed the songs he wrote for the stage in unsuccessful attempts to break into pop. Both Yvonne Elliman’s 1973 track Happy Ending and More Than You Deserve, an early single by one of Steinman’s regular cast members, Meat Loaf, offered the sound of the writer attempting to fit into then-fashionable trends for laid-back rootsy rock with perhaps inevitable results; fitting in and being laid-back were not roles to which Steinman was suited. The breakthrough came with Bat Out of Hell, which had its roots in another musical, Neverland. It transformed into a seven-track album with the aid of producer Todd Rundgren, whose enthusiasm seemed to be rooted in the belief that the whole thing was an elaborate joke: “This big, fat, operatic guy doing totally over-the-top, overwrought, drawn-out songs … I can’t believe the world took it seriously”.

Rundgren also believed that the album was intended as an affectionate parody of Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run, a huge hit during the period it was recorded. You could see why he came to that conclusion. Steinman was a Springsteen fan – employing members of E Street Band on Bat Out of Hell – but loved him because he thought he was “showbiz”: “All the people around him will tell you that he’s ‘real’ and he’s ‘street’ and he’s ‘grit’,” he scoffed. Bat Out of Hell shared both Springsteen’s subject matter – small-town angst and dreams of escape, teenage romance – and his love of Phil Spector. But Steinman’s approach was closer to that of one of Spector’s girl-group svengali rivals: Shadow Morton, the alcoholic mastermind behind the Shangri-Las’ incredible mid-60s singles, a series of outrageous teenage melodramas on which parents were defied, bad boys lusted after and umpteen mangled corpses plucked from auto wrecks, all set to sound effect-laden productions, the sound of someone gleefully vandalising the Wall of Sound.

Bat Out of Hell’s title track was effectively one of Morton’s car-crash anthems given the Hollywood blockbuster treatment – “I never see the sudden curve until it’s way too late”. But the album’s centrepiece was the astonishing Paradise By the Dashboard Light, the story of a backseat fumble and its consequences turned into eight and half minutes of scenery-chewing vocals and episodic songwriting that reached a pinnacle of ridiculousness when it unexpectedly transformed itself into a disco track with an excited sports announcer relaying the progress of the sexual encounter: “He’s trying for third base! Here’s the throw! Holy cow!”

For all its preposterousness, Paradise By the Dashboard Light was both undeniably exciting and richly melodic. Furthermore, something about its central conceit – a bickering couple trapped in a loveless marriage, looking back at the romance that had started it – rang true. Perhaps that was why Bat Out of Hell sold, its gradual success bolstered by relentless touring and TV appearances on which the suitably theatrical performances of Meat Loaf and Karla DeVito – the latter deputising for Bat Out of Hell’s female vocalist Ellen Foley – leapt from the screen.

But the touring effectively scuppered its follow-up, Bad for Good: with Meat Loaf’s voice temporarily ruined, Steinman elected to release it as a solo album. It was a mistake. Bad for Good had the songs, not least closer Rock and Roll Dreams Come Through, effectively Thank You for the Music for people who would balk at the idea of buying an Abba record. But Steinman’s songs always required a powerhouse vocalist, who sang with total commitment (“Obviously playing a role, but it’s obviously genuine,” as Steinman put it) to provide an emotional grounding amid the high-camp extravagance – and one thing Steinman wasn’t was a powerhouse vocalist. By the time he and Meat Loaf reconvened, the momentum was lost. Despite its brilliant title track, which starred a guest vocal from Cher and a LatinAmerican-inspired interlude into the usual bug-eyed mayhem, 1981’s Dead Ringer was a flop in the US.

Its failure affected Meat Loaf more than Steinman. Two years later, the latter was back, in the company of Bonnie Tyler, whose suitably committed rendering of Total Eclipse of the Heart was a 6m-selling transatlantic No 1; in America, it kept another Steinman song, Air Supply’s Making Love Out of Nothing at All, from the top spot. Meat Loaf was left grousing that he should have been singing them, but Steinman’s collaboration with Tyler proved fruitful: the album Faster Than the Speed of Night was vastly successful, 1984’s Holding Out for a Hero another huge single.

Steinman was next employed to produce Def Leppard, but the arrangement was a disaster and swiftly collapsed. He worked with goth titans the Sisters of Mercy, which turned out to be an improbable masterstroke: his grandiosity turned a band whose ambition had been hobbled by their reliance on a tinny drum machine into a genuinely epic-sounding band on 1987’s This Corrosion and Dominion/Mother Russia: “We needed something that sounded like a disco party run by the Borgias,” offered the band’s Andrew Eldritch of the former, “and that’s what we got.”

Moreover, Steinman had an unerring ability to successfully cannibalise his own failures. The solitary album by Pandora’s Box didn’t even warrant a US release, which enabled him to subsequently uproot its single, It’s All Coming Back to Me Now, and present it to Céline Dion, who turned it into a multi-platinum 1996 single. Whistle Down the Wind failed to set the box office alight, but, excerpted from the musical and performed by Boyzone, No Matter What became another huge hit, and the boy band’s solitary US success.

By then, Steinman had reunited with Meat Loaf for Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell. It said something about how far removed from prevalent mid-70s trends the original had been that they could effectively repeat its formula two decades on, in a completely different musical climate, to huge success: the single I Would Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That) went to No 1 in 28 countries. As if to prove his eclecticism, he went on to work with Take That, co-producing their single Never Forget with UK house duo Brothers in Rhythm, a collaboration so improbable it made working with the Sisters of Mercy look like the height of normality.

Steinman never quite recaptured that level of commercial success in the 2000s and 10s, an era when pop music increasingly took itself more seriously than Steinman might have thought permissible. He continued squabbling with Meat Loaf: at one point the singer attempted to sue him for $500m, and was later reduced to recording covers of songs Steinman had given to other artists for Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster Is Loose and 2016’s Braver Than We Are. A succession of stage projects – including a Batman musical and a version of The Nutcracker in collaboration with Monty Python’s Terry Jones – never came to fruition. Another musical, Dance of the Vampires was a disaster. Steinman was fired by the producer, who also happened to be his long-term manager, and the show eventually lost $17m – though a stage version of Bat Out of Hell did inevitably appear in 2017 and has toured ever since.

But by then, you had to wonder if Jim Steinman actually needed any more commercial success. He had defied the critical maulings regularly dealt out to him to become one of the most successful songwriters of his generation. Moreover, his songs have lasted: clearly, Total Eclipse of the Heart, Dead Ringer for Love and It’s All Coming Back to Me Now are destined to be wailed en masse at drink-fuelled karaoke sessions for the rest of eternity. He cut a unique figure in rock music, but it turned out that millions of other people agreed with the self-styled “little Richard Wagner” and his philosophy of musical excess: the silly things were kinda the things that were all right.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies