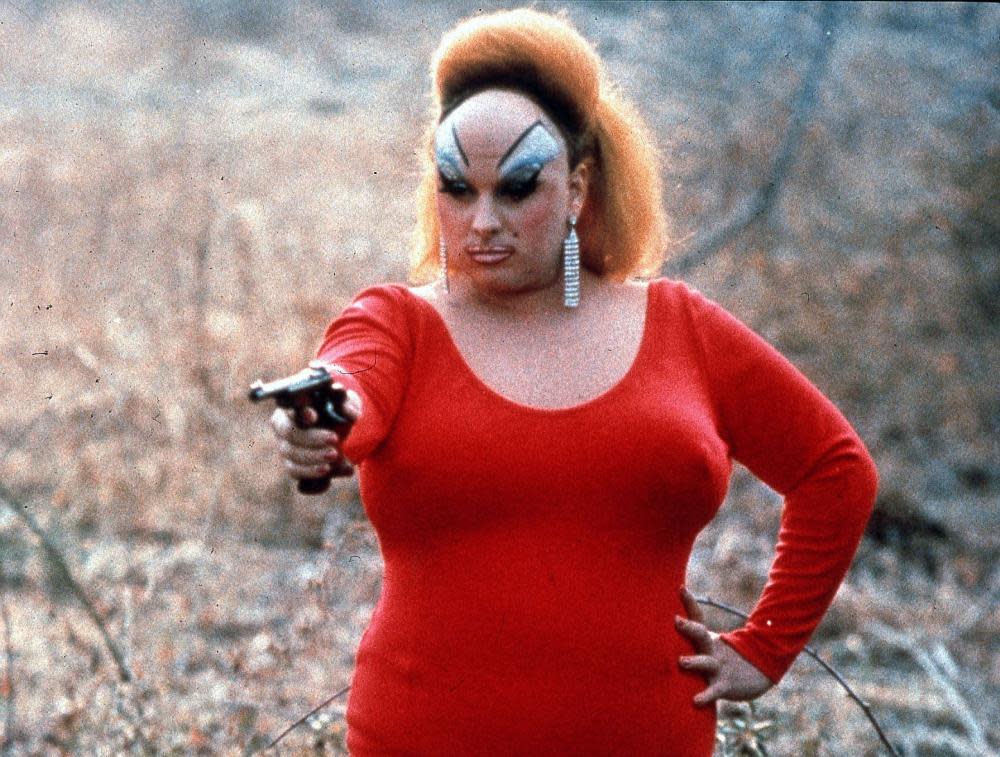

How John Waters and Mink Stole made notorious cult film Pink Flamingos

John Waters, director

I went to the Manson family trial right before I made Pink Flamingos. It had a huge effect on me. They were the real-life filthiest people alive. That’s the title that Divine’s character in the film wants. Pornography was also just becoming legal, which left exploitation and art films with nowhere else to go. So I tried thinking up things that weren’t illegal on film yet, but should be. I always knew that eating dog shit was going to be the kicker ending.

We shot it in the fall of 1971 and the early months of 1972. I wrote it as I went along. My dear father, who never saw the film, paid for it – $12,000 – which I later paid back with interest. We had been arrested making our previous movies, so we went to my friend Bob Adams’s farm in Phoenix, Maryland, and our production designer, Vincent Peranio, got the trailer Divine lives in for $100 in a junkyard. We did these endless 22-hour days in the freezing cold that you can only do when you’re young and crazy and driven.

The film looks raw, but it was all very rehearsed. No one was high in the party scene: it was 8am on a Sunday. The guy who makes his asshole “sing” was a straight guy a friend of mine knew, who said he did it for yoga exercises. He came over and offered to do it for me. I said: “No, I believe you.” I was kind to him, I didn’t make him do it in front of everyone; I filmed the party on a separate day. I was speechless myself when he did it.

Divine was nothing like that character in real life. He was a shy man; he would never go in drag unless he got paid. But he used the rage he had from being bullied in high school to make that character. Eating the dog turd was no big deal; there are no camera cuts, you can see it is real. He gagged. But after Pink Flamingos, it was hard for him. People thought he lived in that trailer and ate dog shit.

As soon as I saw it with an audience, I knew it could be a hit. Even if you hated it, you couldn’t not tell someone about it. The night it opened at the Elgin theatre in New York, my life changed; El Topo, the first “midnight movie”, had just closed there, so it was the perfect place to show it. Within a week it was selling out. But I lost every time we were in court for obscenity. Even MoMA buying a copy didn’t save us.

I once showed it at a children’s birthday party – for the daughter of my casting director, Pat Moran. I think we covered their eyes for the sex scenes. But children always loved Divine, because he was like a clown. I do remember some of them running through the apartment screaming. When I look back on it, we should’ve all been locked up. But the daughter is now a very happy, well-adjusted TV producer, so no harm was done. Their parents loved them and made them feel safe, even if they had to watch a singing asshole.

Mink Stole, actor

I had already made three movies with John, who I had met through my sister. There was a hugely sacrilegious element to his early films that I was very happy to participate in, having grown up Catholic like him. When he asked me to be in a movie, I would say yes without knowing anything about it. All I knew with Pink Flamingos was that it was going to be a rivalry, vying to be the filthiest people alive. And that Divine would win, and that we would lose and be humiliated. I’m generally a pretty decent gal in real life, so it was fun to get permission to really be vile.

Most of my scenes were filmed in the actual house where John and I were roommates. It meant I was never late for work. My character Connie Marble’s clothing was all mine. Dying my hair that shade of red was difficult to do in the 1970s – you couldn’t just run to the drugstore for some dye. I had to bleach my hair white, and then I coloured it with red ink in shampoo. David Lochary, who played my pervert husband, did it with the blue ink out of a Magic Marker. We both dyed our pubic hair too.

My coat almost got set alight in the scene when we torch Divine's trailer. Any number of catastrophes could have happened that day in the woods

The only thing I balked at was that John wanted me to set my hair on fire. But my coat did almost get set alight in the scene when we torch Divine’s trailer. I was always terrified of forgetting my lines, especially when everything is the master take and you have to start over if you mess something up. So I was focused on throwing a torch into the trailer; we had been spraying real gasoline around, and it came very close to my coat. Any number of catastrophes could have happened that day way out in the woods.

The gods of cinema were looking down on us with kindness. Nobody at the time was doing what we were doing. I lost friends because of the film and I gained them. My family was mortified, but my mother ended up converting to the cult of John Waters. She disapproved of him and of what we were doing, but he could always make her laugh. All of the people I worked with became my friends, my other family. We still know and love each other 50 years on.

• Pink Flamingos is screening at the Rio cinema, London, on 28 March, with a Mink Stole Q+A. Mr Know-It-All by John Waters is published by Little, Brown.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies