Leaving Neverland: Why James Safechuck's testimony doesn't necessarily need to add up

Note: The following article contains discussion of sexual misconduct allegations that some readers may find upsetting.

It's been a month since Leaving Neverland debuted on Channel 4 in the UK, and yet viewers are still arguing over the allegations made in the two-part documentary.

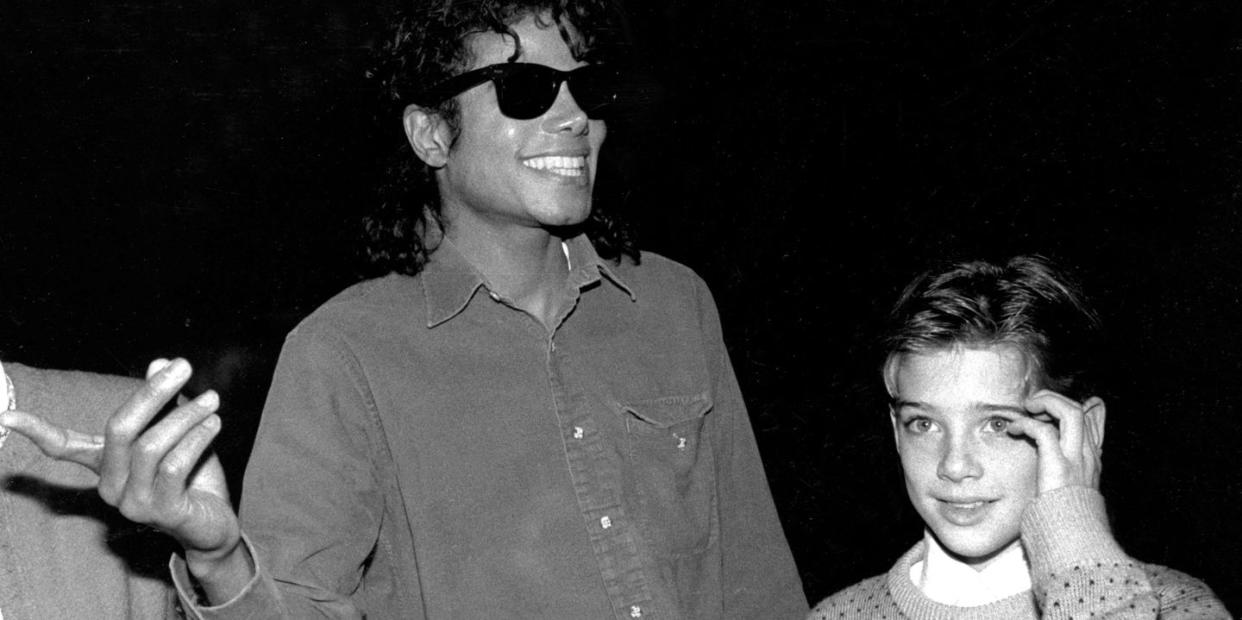

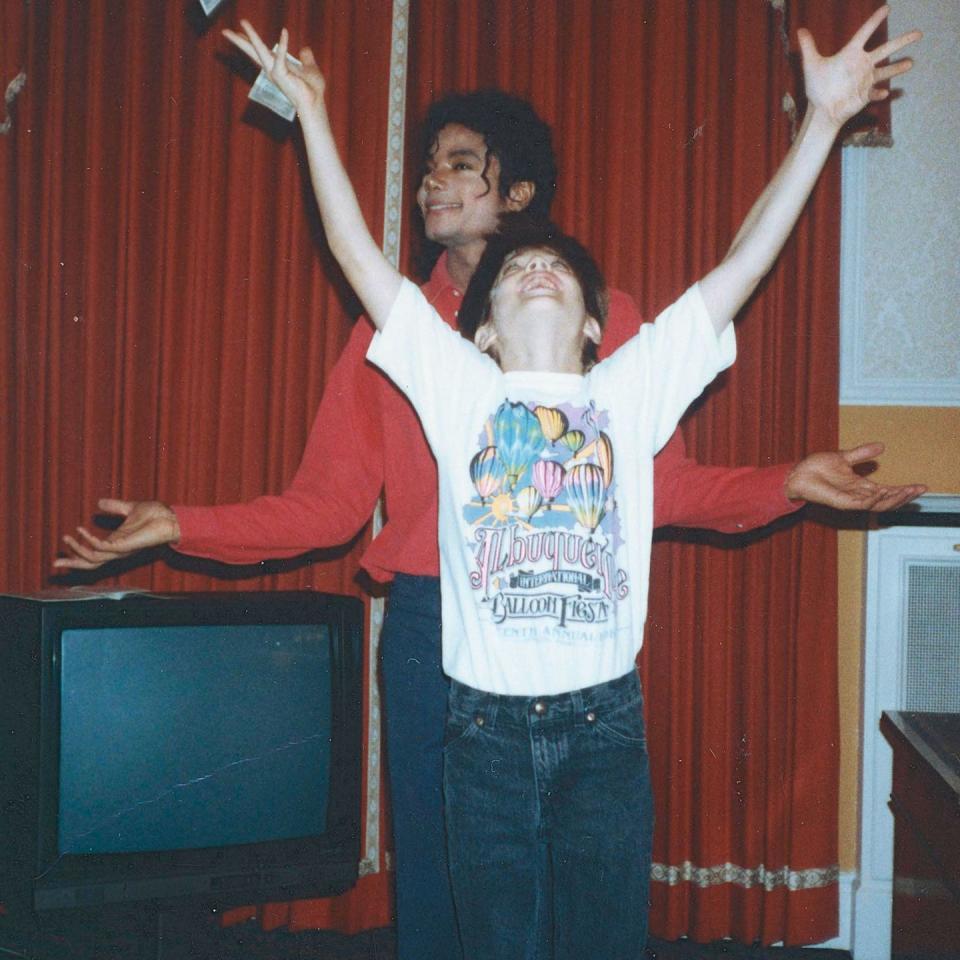

The series centres on the testimonies of two men: Wade Robson and James Safechuck. Now adults, they have accused Michael Jackson of sexually abusing them when they were children. The Jackson estate has vehemently denied all claims against the late singer and condemned the documentary.

Related: What you need to know about the Michael Jackson allegations as Leaving Neverland airs

The allegations were described in graphic and painful detail in Leaving Neverland. While it left many with very little doubt as to their credibility, there are some that have criticised the programme and sought conflicting evidence to undermine the accounts of the two men.

Ofcom received 230 complaints about the docu-series, with viewers claiming that it misled them because the allegations made in the film hadn't been proved.

It was, however, decided that Leaving Neverland would not face investigation by TV regulators. Ofcom's statement read: "We understand that this two-part documentary gave rise to strong opinions from viewers.

"In our view, the allegations were very clearly presented as personal testimonies and it was made clear that the Jackson family rejects them."

There have also been a number of so-called discrepancies levelled at director Dan Reed, the latest of which focuses on one room in the Neverland Ranch.

Related: The biggest revelations to come from the Leaving Neverland documentary

Recent reports suggested that James Safechuck couldn't have been molested in the Neverland train station between 1988 and 1992 (when the abuse was said to have occurred), because the station wasn't actually built until 1994.

Mike Smallcombe, Jackson's former biographer, shared construction permits on Twitter that showed approval for the building works in September 1993.

Addressing this detail, Leaving Neverland director Dan Reed replied: "Yeah there seems to be no doubt about the station date. The date they have wrong is the end of the abuse."

Many seemed to jump on this as some sort of admission that a fact was 'wrong', with some arguing that Reed was now backtracking in light of this detail. He has since confronted this claim, arguing that "James [Safechuck] was present at Neverland before and after the train station was built."

"In fact he took photos of the completed station which we included in the doc," Reed added. "And his sexual contact with Michael lasted into his teens. That’s all in the film."

This raises a bigger point: wWhile it's always good practice to try and corroborate allegations, discrepancies over dates do not necessarily hold up as a means of undermining an entire account.

It is not uncommon for people who have experienced abuse or trauma to struggle when recalling specific details such as dates and times – even though they may have really vivid and clear memories relating to the traumatic event itself.

This can be particularly problematic for a victim if and when they decide to come forward to the authorities. Police and prosecutors, for example, may rely on these details to establish context and validity.

"There is this tragic discrepancy between what is expected within the criminal justice system and the nature of trauma memories and how people are likely to be reporting them," Amy Hardy, a clinical psychologist at Kings College London, told the BBC in a 2018 article dismantling myths around sexual assault.

Hardy also described how traumatic memories are processed differently, with the brain focussing on the immediate, rather than the bigger picture.

"When we are under threat, it is much better that we focus on what we are experiencing, which triggers us into fight, flight or freeze-type responses, than to focus on the bigger meaning and making sense of it," said Hardy.

This would be heightened if someone was to "dissociate", which is "where the cognitive part of the brain shuts down", during the trauma.

David Lisak, a clinical psychologist and researcher whose work focuses on non-stranger sexual violence, spoke to Cosmopolitan US for a similar article in 2014.

Lisak explained that "somebody's experience of trauma will have extremely vivid memories of disconnected fragments of the experience" but that "at the same time [they] will have real difficulty putting that all together into any kind of coherent format."

"There's an expectation that the person who has had this traumatic experience will provide an account and no matter how many times you ask them to provide an account, you always get the same answer," Lisak said. "There's no way that someone who has been traumatised will be able to do that."

He explained that "when you're questioning a person who has gone through that, what you'll get are halting responses that can seem confused or uncertain" before adding that "it's extraordinarily unlikely that they will be able to provide absolutely consistent statements one after another."

Of course, we cannot speak for James Safechuck or his personal experience.

But when it comes to the wider conversation around the behaviour of alleged victims, particularly with what we may see on screen as these kind of documentaries continue to grow in popularity, it's an important angle to be aware of. Even more so if viewers are going to continue to project their own expectations of behaviour onto those that feature in them.

Leaving Neverland aired on Channel 4 in the UK and HBO in the US.

Readers who are affected by the issues raised in this story are encouraged to contact the NSPCC on 0808 800 5000 (www.nspcc.org.uk). Readers in the US are encouraged to contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline on (1-800-422-4453) or the American SPCC (www.americanspcc.org).

Want up-to-the-minute entertainment news and features? Just hit 'Like' on our Digital Spy Facebook page and 'Follow' on our @digitalspy Instagram and Twitter account.

('You Might Also Like',)

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies