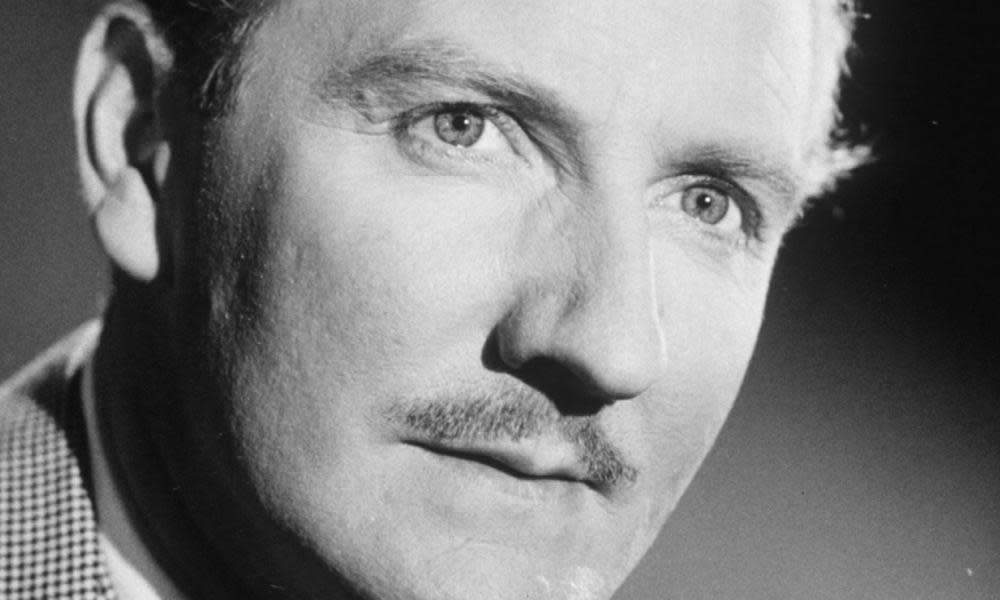

Leslie Phillips obituary

Leslie Phillips, who has died aged 98, was a light comedian of the old school, closely associated with a roster of smooth-talking cads and lady-killers in the series of Carry On and Doctor films he graced from the late 1950s onwards.

He first coined his trademark phrase “I say, ding dong!” as the lubricious Jack Bell in Carry On Nurse (1958) and made the simple greeting “hello” sound like a frolicsome, impure invitation, earning him the nickname “King Leer” and lending itself to the one-word title of his immensely entertaining autobiography (2006).

He became a national Sunday lunchtime institution on BBC Radio’s The Navy Lark, in which he appeared as a hopeless lieutenant on HMS Troutbridge – alongside Stephen Murray, Jon Pertwee, Tenniel Evans, Heather Chasen and Ronnie Barker – between 1959 and 1977. It was never clear – deliberately so – whether he was a simpleton or a crook in this company of Royal Navy undesirables on the recommissioned frigate stationed off Portsmouth.

Despite his louche and carefree acting persona, Phillips was an ambitious and hard-working artist who in the late 60s toured the world in his own West End hit, The Man Most Likely To... – he rewrote Joyce Rayburn’s play, took the lead, produced and directed it.

He joined the Royal Shakespeare Company in his mid-70s and featured in several major films, including George Cukor’s Les Girls (1957), with Gene Kelly and Kay Kendall, Sydney Pollack’s Out of Africa (1985), Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun (1987) and Roger Michell’s Venus (2007), playing an old thespian alongside Peter O’Toole and Richard Griffiths.

His prodigious work-rate derived from his impoverished background in Tottenham, north London, where from an early age he was the family breadwinner. His suave and polished persona was as much a creation as that of Terry-Thomas or Rex Harrison, and it gave his acting an edge of seditious malice, an air of unofficial naughtiness.

With the confidence that came from being told frequently he was a good-looking lad he developed a taste for fast cars, high living and beautiful women when the money rolled in. For a time he was the highest earning actor on the West End stage, and joined the Ibiza crowd in the 70s, keeping a house there in a colony of artists and writers that included his great friend Denholm Elliott.

He was married three times and had a long relationship (between the first and second marriages) with Caroline Mortimer, the daughter of the writers Penelope and John Mortimer.

This was all a far cry from his humble beginnings as the third child of Cecelia (nee Newlove) and Frederick Phillips, a maker of cookers at Glover & Main in Edmonton. The family moved from Tottenham to Chingford, by the river Lea and on the fringes of Epping Forest, in an attempt to improve Frederick’s health, but he died of a chest illness in 1935, and Cecelia, spotting an advert in a newspaper, packed her son off to the Italia Conti school to train as an actor.

Phillips had shown talent in plays at Chingford school and soon supplemented his income from delivering papers and singing at weddings and funerals in All Saints Church, Chingford, by playing a wolf – his stage debut, in 1937, aged 13 – in Peter Pan, starring Anna Neagle, at the London Palladium.

After a spell as a cherub in a stained glass window in Dorothy L Sayers’s The Zeal of Thy House at the Garrick, he returned to the Palladium for the 1938 production of Peter Pan, now playing John Darling in a cast led by Seymour Hicks (“vile”, according to Phillips) as Captain Hook and Jean Forbes-Robertson (“lovely”) as Peter.

By the time he was called up in 1942, he had sung in the children’s chorus at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and acted with John Gielgud and Marie Tempest in Dodie Smith’s Dear Octopus at the Queen’s – the start of a long association with the producers Binkie Beaumont and HM Tennent – and Vivien Leigh and Cyril Cusack in Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma at the Haymarket.

Everyone in the business liked him, and this would stand him in good stead after the second world war. He sounded posh enough to gain a commission as second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery, transferring to the Durham Light Infantry, where he was put in charge of the Suffolk transit camp at Chadacre Hall, before being invalided out in 1944.

His first post-demob job was in the box office at the Lyric, Hammersmith. He played Guildenstern in Hamlet at Dundee rep, and discovered his talent for light comedy in a stint at the York rep. His first major West End role was in a sentimental comedy, Daddy Long Legs (1946), at the Comedy (now the Harold Pinter).

The first of more than 100 film appearances came in Lassie for Lancashire (1938). The Hollywood adventure of Les Girls could have led to a latter-day C Aubrey Smith-style career in California, but he preferred London and Pinewood Studios – he was the last living actor to have worked there when they opened. He was also in the cast of the first live BBC broadcast from Alexandra Palace in 1948 – Morning Departure, set on a wartime submarine with Michael Hordern – and played his first BBC television lead in 1952 in My Wife Jacqueline (opposite Joy Shelton), a pioneering but mediocre (he said) sitcom about married life, broadcast live from Lime Grove in six 30-minute episodes.

Over the next 10 years he established himself in the Doctor films as the philandering consultant, Dr Tony Burke, and in the Carry Ons, usually stuck on Joan Sims. He followed the huge stage success of the superb farce Boeing-Boeing (taking over from David Tomlinson in 1963) with the first series of Our Man at St Mark’s on television, in which he played an eccentric new village vicar. When his affair, while still married, with Caroline Mortimer became public, he was no longer deemed suitable as a clergyman, and was succeeded in later series by Donald Sinden.

Opening at the Vaudeville in 1968, he played 655 performances as the upper-class lounge lizard Victor Cadwallader in The Man Most Likely To… and later toured to Australia (where one audience member in Adelaide was reported to have literally died laughing), New Zealand and South Africa, defying the cultural boycott and working in the townships as well as the commercial theatres.

He played in another “saucy” comedy, Sextet, at the Criterion in 1977 (Julian Fellowes was also in the cast), and then led a hugely successful revival of Ray Cooney and John Chapman’s Not Now, Darling at the Savoy in 1979, followed by another world tour.

Phillips said that he at last broke his own mould when cast by Lindsay Anderson as a dithering, weak-willed Gayev in The Cherry Orchard at the Haymarket in 1983 (Joan Plowright played his sister), and he went even further in a brilliant revival by Mike Ockrent of Peter Nichols’s lacerating comedy Passion Play at the Leicester Haymarket, and then Wyndham’s in the West End, in 1984. In 1990, he popped up unexpectedly in The Comic Strip and, also on television, in Chancer, which launched Clive Owen, playing Owen’s scheming boss.

There was now no pattern or predictability as he entered the last phase of an astonishing career. He played the professor in another Chekhov, Julian Mitchell’s rewrite of Uncle Vanya, August, with Anthony Hopkins at Theatr Clwyd, Mold (1994), and then joined the RSC to play a fruity saloon bar roué of a Falstaff in Ian Judge’s The Merry Wives of Windsor (1996) on the main Stratford-upon-Avon stage and, in the Swan, a cynical hotelier in Steven Pimlott’s discovery of Tennessee Williams’s “lost” fantasia, Camino Real. Also in 1996, he played a frisky old Sir Sampson Legend in Love for Love by William Congreve at the Chichester Festival theatre.

On the Whole, It’s Been Jolly Good was the appropriate title of a Peter Tinniswood one-man play he took to the Edinburgh Fringe in 1999, reverting to more raffish type as Sir Plympton Makepeace, a bitterly “dumped” Tory MP from the Shires with no good to say of anyone: “That woman with the loud voice … I think she was the PM but to me she looked like a power-mad swimming baths attendant.” His last stage appearance came as an ageing judge with a back problem in John Mortimer’s Naked Justice at the West Yorkshire Playhouse in 2001.

In the new millennium he had good TV roles in Monarch of the Glen and Miss Marple. An excellent television version of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy, adapted by William Boyd (2002), had him in the role of Gervase Crouchback, father of Daniel Craig’s anti-heroic Guy, and he regained his dog collar in Nigel Cole’s charming movie Saving Grace (2000), starring Blenda Blethyn. For the Harry Potter films he voiced the Sorting Hat at Hogwarts.

In 1997 he received a lifetime achievement award from the Evening Standard, and 10 years later another from the Critics’ Circle. In 1998 he was appointed OBE, and in 2008 CBE.

Phillips married the actor Penelope Bartley in 1948, and they had two sons and two daughters. They divorced in 1965, and in 1982 he married the actor Angela Scoular; she took her own life in 2011. Two years later he married Zara Carr, and she survives him, along with his children.

• Leslie Samuel Phillips, actor, born 20 April 1924; died 7 November 2022

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies