In lockdown, I've learned there's no substitute for a real pub quiz

“What do the following have in common? Severe; just; involuntary movement in response to a stimulus; slow to understand or unwilling to try to understand.”

There’s a lot of intense whispering between my teammates as I frantically search my brain for solutions. It’s not my first time attending the cryptic pub quiz at the Mill in Cambridge, so I’m getting used to the curveball questions. Frank, the quizmaster, perches on a stool watching the hushed chatter that fills the pub.

Most days during the pandemic, I’ve been dreaming of leaving my flat and heading to my local pub to meet a group of friends indoors. It’s a small ambition, but in it there’s a pub dog, groups of people I half recognise, and it’s so busy you can barely get an elbow on the bar. In the true ideal, it’s also the night of the pub quiz.

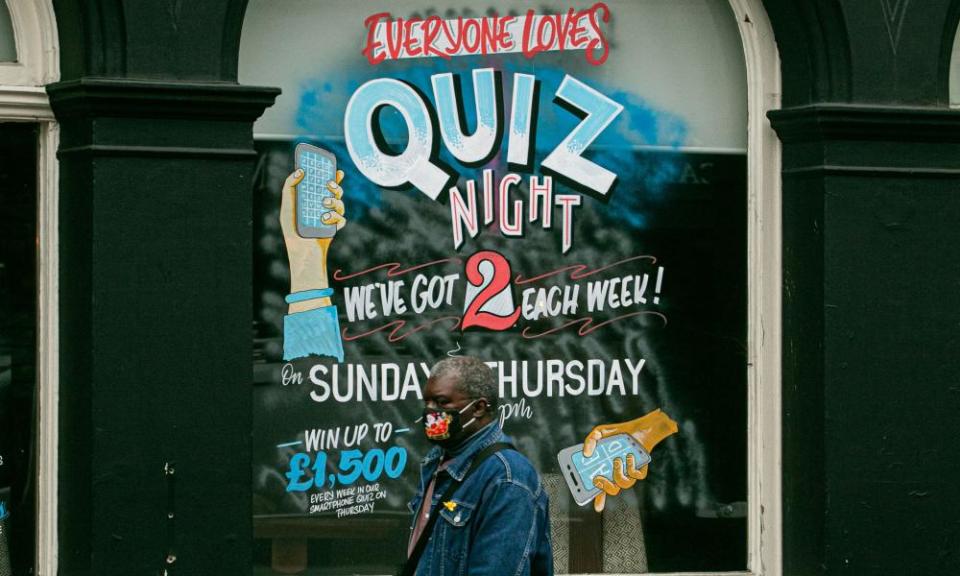

It’s a British tradition that has surprising resilience. Pub quizzes kicked off in the 1970s as a way to coax in punters on weeknights, gained increasing popularity and are now fully established as a national institution. It’s estimated that almost most half of the UK’s 40,000 pubs hosted quizzes prior to the pandemic.

The British are quiz-obsessed. In our television habits, from University Challenge to Mastermind, there’s a hunger for trivia. Even a large segment of our comedy is framed like a quiz, with panel shows doubling as a mock test of current affairs. In the entertainment vacuum of the first lockdown, this tendency became even more pronounced, with people up and down the country organising quizzes on Zoom.

The online quizzes weren’t all that bad: the digital transition opened up new ways of bringing people together. For some quizmasters, audiences have hugely increased, with hundreds of teams turning up each week via YouTube or Facebook Live to try their luck. Entry fees have either been used to prop up struggling establishments and hospitality workers or as fundraisers for local coronavirus action groups.

And yet, like so many of the social institutions that have been reimagined for an online, coronavirus era, something just doesn’t feel right about the Zoom pub quiz.

What it really needs is a middle-aged man with a faulty mic shouting questions over a hubbub, the quiz sheet sticky with ale and questions about the 1970s that I can’t answer. The picture round needs to be printed in blurry, indecipherable monochrome and should be handed to the person on the team with the best handwriting. There will be bickering about whether that really is a young Alison Steadman or if it’s some woman off Strictly.

Competition is certainly important, especially if there’s a decent prize on offer, but pub quizzes are primarily social events. Many teams will turn up habitually, despite getting 15 out of 50 each time. There’s a strange camaraderie in swapping quiz sheets with neighbours, in hearing roars of laughter across a busy room and in recognising the same groups of people week in, week out. Even in London, a city of 9 million people, the same clusters of friends and families can often be found in the same corner of a pub every Monday or Thursday.

It’s a funny way to measure your life, but I know that mine has reached a level of stability when a pub quiz becomes part of the weekly routine. I’ve lived in three different cities in the past three years and usually, a couple of months after each move, I find myself heading to the same bar with surprising regularity.

The infamous pub quiz at the Mill was the start, where my team tragically fell short each week against the same groups of strangers. (The answer to the question at the beginning? “ANGLES”. “Of course,” everyone groaned as it was read out: acute, right, reflex, obtuse.) It was as good an excuse as any to do something social on a Monday. One week, the picture round was swapped with a plate of tortilla chips for each team, and we had to identify the seven spices they had been cooked in.

When I moved to Copenhagen, I found myself attending a pub quiz with friends religiously. It provided a slice of structure to chaotic life in a new city. Having never won in the UK, our group (named “It Started With A Quiz”, we panicked the first time we attended), somehow had the accumulated knowledge to lead us to victory most weeks against our rivals, “Fluffy”.

And then in London over the past year pub quizzes provided some unexpected grounding. Some of my biggest celebrity run-ins have been at the quiz: some friends and I were trounced by Sir Ian McKellen at his own pub last year (the Grapes in Limehouse). And I’ve been heading to the Pineapple’s quiz in Kentish Town with my boyfriend and sister, whenever possible.

The unintentional community and the casual, offhand fun of it is what matters most. For me, the online pub quiz just feels too earnest. Even without a local, walking into a new pub quiz somehow feels like entering a loosely structured group of neighbours. This regular gathering of weak ties is what makes the pub quiz valuable, and worthy of dreaming about in turbulent times.

Eleanor Salter writes about climate, culture and politics

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies