Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at Tate Britain review: a great show by a great artist

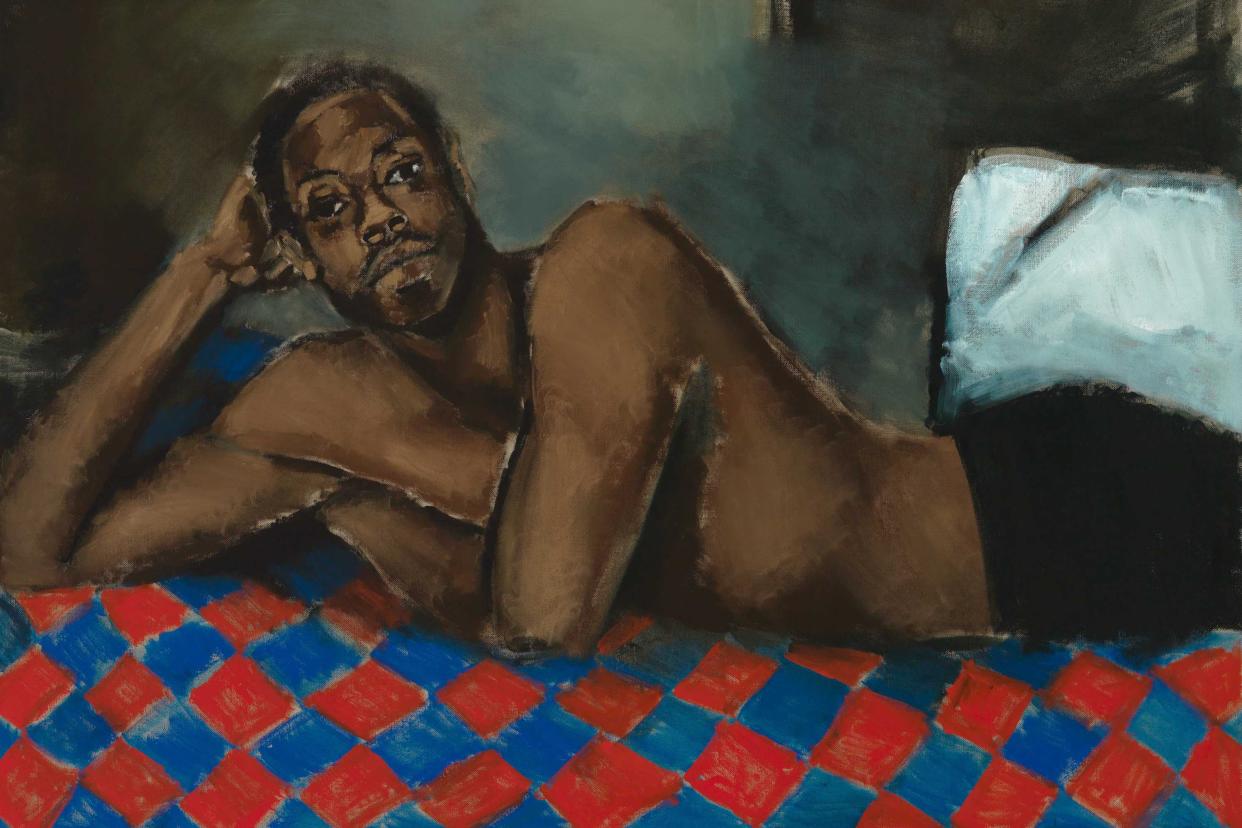

Detail from Tie the Temptress to the Trojan 2018

(Lynette Yiadom-Boakye)Among many great moments in this show — twice Covid-delayed but now open — is a pair of vast paintings of what appears to be the same figure. A Black man with longish hair, white shirt and black trousers, he sits side-on but turns, meeting our gaze and laughing.

He’s an enigma. What prompts his amusement? Is that a menace in his laughter or is this conspiratorial mirth? He’s so vividly conjured, he seems drawn from life. And yet he’s not — Lynette Yiadom-Boakye composes her figures from scrapbooks and family albums, from memory and historic paintings.

And because he’s invented, the London-born artist can take him anywhere she likes. In Wrist Action (2010), he has an absurd pink glove that emerges like an apparition from the otherwise gloomy light. In Bound Over to Keep the Faith (2012) a rope is tied around his waist.

Yiadom-Boakye says she thinks of her protagonists as “people known to me”; the novelist Zadie Smith wrote that they enter our imaginations like literary characters. You find yourself pondering their hinterland, their present, their future. We see them in indistinct landscapes and interiors, perhaps on a stage where they’re performing, but they’re never rooted in time or place.

Condor and the Mole, 2011

Lynette Yiadom-BoakyeTo encourage this imaginative realm, the show is hung intuitively rather than chronologically, so the subjects and forms dictate the flow, with aspects reappearing rhythmically. Not just the figures but their dress and accessories: a fox fur, with a crudely drawn face; a feathery ruff.

And it’s paint that allows them to be in this constant state of shifting and becoming. Yiadom-Boakye pulls them in and out of focus, in a glorious battle between image and pigment. The figures’ heads can be perfectly realised but their legs or hands might be barely defined or lost in abstraction.

Her touch is sublime. She animates a face with a few marks and patches of bare canvas. She uses colour beautifully: apparently monochrome paintings are lit up by rich hues up close. Elsewhere, colour saturates the canvas, as in the red clothing worn by figures in several paintings.

That red evokes a great work by Walter Sickert, an artist who, like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, never seems far from her thoughts. This show brims with a love of paint: what it’s done in the hands of these great artists, and what it can still do today, as Yiadom-Boakye brings her entrancing characters into being.

Until 9 May (020 7887 8888, tate.org.uk)

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies