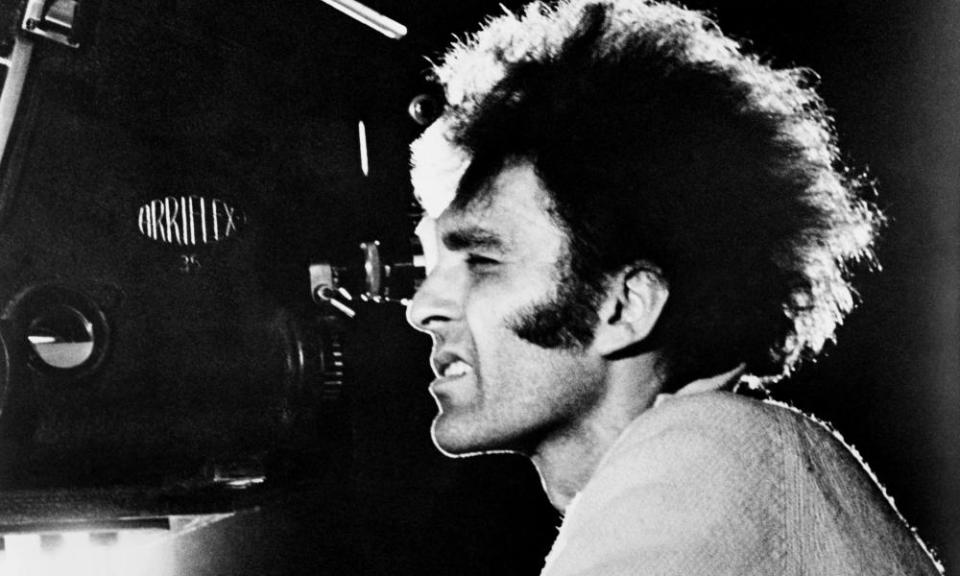

Monte Hellman obituary

Whenever the name of the director Monte Hellman is mentioned, it is accompanied by the word “cult”. It is possible that Hellman, who has died aged 91, gained cult status because of his reputation as a maverick, like his favourite actors Jack Nicholson and Warren Oates, and because his films were so few and far between. After Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), his most accomplished and celebrated movie, Hellman had only five full-length features credited to him.

Nevertheless, he was not idle for all that time. He taught film-making at the California Institute of the Arts, and worked on various projects for other people, some uncredited. For example, Hellman finished two pictures in post-production, the Muhammed Ali biopic The Greatest (1977) and Avalanche Express (1979), after the deaths of their directors, Tom Gries and Mark Robson respectively.

He directed an episode of Baretta (1975), the TV crime series starring Robert Blake, and was second unit director on Samuel Fuller’s second world war drama The Big Red One (1980) and on the science fiction hit RoboCop (1987). He was also an executive producer on Quentin Tarantino’s debut feature Reservoir Dogs (1992). However, none of this work put him in the public eye, and he continues to be remembered principally for Two-Lane Blacktop.

Born in New York City, Monte was the son of Fred Himmelbaum, who ran a grocery store before becoming an estate agent, and Gertrude (nee Edelstein), a department store worker. He studied drama at Stanford University and film at UCLA. Then he started a small theatre company in Los Angeles, the opening play being Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

Nine months later, the owners of the theatre decided to tear the building down and turn it into a movie theatre. Roger Corman, who was one of the investors in the theatre, advised Hellman to go into movies and offered him a job. This was in 1959, when Corman was producing a stream of Z movies aimed at the drive-in youth market with its taste for science-fiction horror with tatty special effects, cut-price monsters and unknown casts.

Hellman’s first directorial effort was Beast from Haunted Cave (1959), which promised audiences “screaming young girls sucked into a labyrinth of horror by a blood-starved ghoul from hell”. Hellman later admitted being rather embarrassed by it, “not because of the kind of picture it was, but just because of my own lack of experience”. This was followed by further chores for Corman, directing, co-writing and editing. It was while editing The Wild Ride (1960) that Hellman got to know the 22-year-old Nicholson, who had top billing as a juvenile delinquent.

In 1964, Hellman and Nicholson went off to the Philippines to shoot two Poverty Row adventures: Back Door to Hell and Flight to Fury, costing around $80,000 each. “I was editing one at night while I was shooting the other, getting by on three hours’ sleep. It’s the madness of a young man … and the locations were hundreds of miles apart, and you can’t scout both pictures before starting to shoot the first.”

Though benefiting from Hellman’s sharp eye for location, the films were both bogged down by laboured, derivative scripts. Therefore it was surprising that about a year after these potboilers, Hellman and Nicholson would collaborate on two of the most original westerns made since the 1950s, Ride in the Whirlwind (1965) and The Shooting (1966).

The experience of making two films back to back was repeated when Hellman took off with a crew of 10 to the Utah desert to film them in just over three weeks on a shoestring. These bleak, enigmatic, existential “anti-westerns” were dismissed at the time, only to be rediscovered and acclaimed (despite or because of the rough edges) years later when Nicholson had become a star of some magnitude.

But it was Two-Lane Blacktop that raised Hellman to cult status. It follows two long-haired car-freaks (the singers James Taylor and Dennis Wilson in their only screen roles) as they head east from California in their 1955 Chevrolet, challenging others along the way, among them an ageing playboy (Oates) in a bright orange Pontiac GTO. The film’s structure is as linear as the road it follows and the cast consists of nameless characters. They are merely called the Driver, the Mechanic, the Girl and GTO. Yet, although the characters are given representative labels, they remain individuals.

What is effective is Hellman’s detachment from his subject, and the way he captures beautifully the empty car lots, late-night diners, the open country and the two-lane backdrop to this American sub-culture. “The thing is you’ve gotta keep moving,” says one of the characters, which defines the road movie.

After the critical success but commercial failure of Two-Lane Blacktop, Hellman started work on Shatter (1974), Hammer Films’ entry into the kung fu genre, filmed in Hong Kong, only to leave the production halfway through when it was taken over by the producer Michael Carreras. On his return to the US, Corman offered him Cockfighter (1974), which Hellman filmed in Georgia because the “sport” of cockfighting was legal in that state. Released to protests and pickets from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the film never found much of an audience, despite several re-editings and retitlings.

However, despite its nasty side, Cockfighter contains a wonderfully enigmatic, taciturn performance from Oates, excellent natural-light camerawork from the cinematographer Néstor Almendros, and pacy, atmospheric direction. The ambivalence at the heart of the film is due to the fact that Hellman never felt comfortable with the subject, and Corman, the producer, felt compelled to add more graphic cockfight sequences and car explosions.

The third and last film that Hellman made with Oates was China 9, Liberty 37 (1978), a spaghetti western shot in Spain, an obvious homage to Sam Peckinpah, who appeared in a small role. Hellman had to wait a further 10 years before he was given the chance to direct another picture.

Iguana (1988), shot largely on location in Lanzarote, was a portrait of a disfigured 19th-century sailor. Almost sunk by its allegorical pretensions, it has some fascination as a typically off-beat Hellman project with an antihero.

According to Hellman, “it was spoiled by a stupid, neurotic producer who couldn’t spend money until the last minute (when it was usually too late). Nothing was prepared in advance. We didn’t have lights until three weeks into the shoot, essential props frequently didn’t arrive until late in the day … I was in a constant state of anger. But I wound up liking the film a lot.”

Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out! (1989), a run-of-the-mill slasher movie, was excused by dedicated Hellman followers as a potboiler, with hopes for better things to come. “In reality, I have always been a hired gun. I have usually taken whatever job came my way. In fairness to my reputation, I did try to make the best of these assignments – usually hiring a new writer to make over the scripts more to my taste. But I was making other people’s movies,” Hellman once said.

His next film was Stanley’s Girlfriend, one of five horror episodes in Trapped Ashes (2006). There was one more feature film to come – Road to Nowhere (2010), a low-budget neo-noir, is a metamovie in extremis. Puzzling and intriguing, it is a film within a film within a film, asking audiences to suspend disbelief by claiming, at the end, that “this is a true story”.

In 1955 Hellman married the actor Barboura Morris; they divorced in 1961. The following year he married Jacqueline Ebeier, with whom he had two children, Jared and Melissa; they divorced in 1972. His third wife was Emma Webster, a writer, and that marriage also ended in divorce. He is survived by his children and his brother Herb.

• Monte Hellman, film director, born 12 July 1932; died 20 April 2021

• Ronald Bergan died in 2020

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies