The Mysterious Case of Babies Buried With Helmets of Other Children’s Skulls

A team of archaeologists working in Ecuador recently discovered something unexpected. At a funerary site dating to around 100 B.C. they unearthed the remains of two babies that were buried with protective “helmets” made from the skulls of older children. So far these burial sites are the only known evidence of using children’s skulls as funerary headgear. Reporting of the discovery has focused on the macabre and gruesome nature of the find, but a closer look shows that we aren’t as far from ancient Ecuador as we might think.

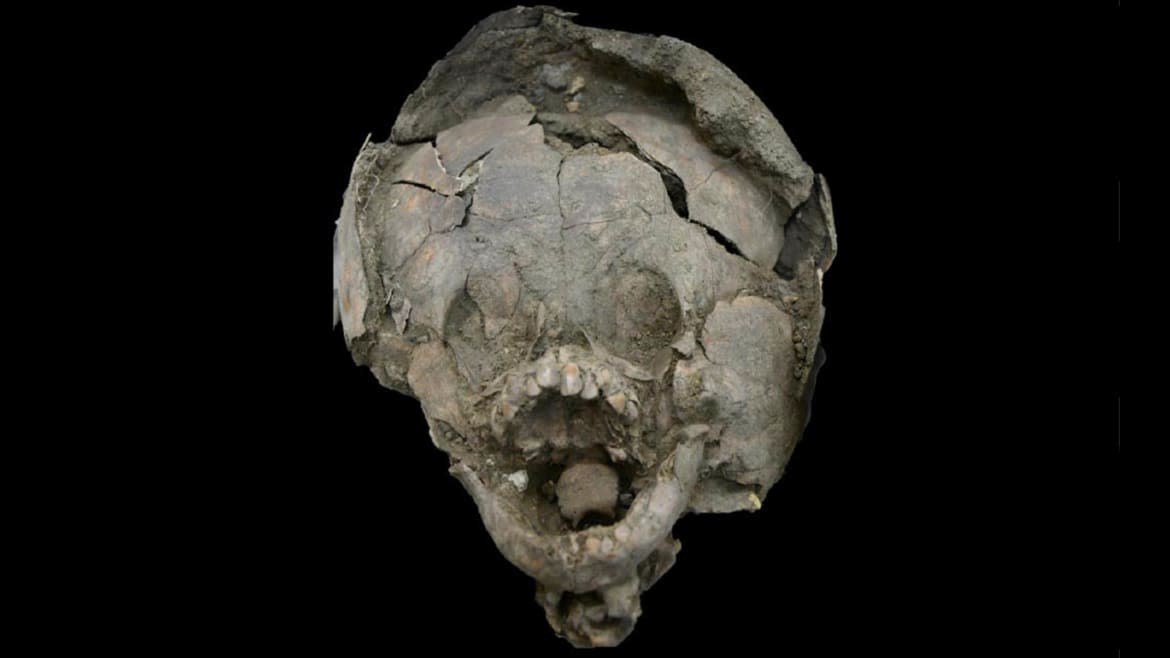

Researchers from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the Universidad Técnica de Manabí in Ecuador made the discovery while excavating at the ritual complex of Salango on the central coast of the country. They published their findings in the academic journal Latin American Antiquity. The two infants were aged about 18 months and 6-9 months when they died; the children whose skulls encased their own were aged 4-12 years and 2-12 years, respectively. The modified skulls of the older children were placed around the heads of the infants so that the baby’s “face looked out and through the cranial vault of the second.” Almost like some kind of modern protective helmets. The discovery raises a number of questions: To whom do these remains belong? Why would people do this? And, what happened to these children?

Heads don’t only make appropriately shaped helmets, they had a particular significance in ancient South American culture and, indeed, globally. After all, our heads are both critically important to life and a powerful tool for recognition and identification. As the archaeologists (Sara Juengst, Richard Lunis, Abigail Bythell, and Juan José Aguilu) write in their study, in South American culture isolated crania, or “trophy heads,” were fairly common. They are generally viewed to be the heads of ancestors or war victims. Heads like these could serve as symbols of the past and of future generations, or as emblems of power and domination. Heads of children, however, were much less prevalent. As Juengst, a professor of anthropology at UNC-Charlotte, told The Daily Beast, “trophy heads [are discovered] pretty regularly but never worn in this manner. And our literature review didn't turn up anything like this anywhere else in the world either.” These nested skull burials are, so far, unique.

The first question, of course, is why would people choose to bury their children in this way? Grave goods (toys, statues, jewellery and so forth) are common in ancient burials in general, but why would some ancient people—in this case the Guangal—develop this unusual mortuary practice? While much is still unknown, the best guess is that the skulls were used to give the infants added protection. Juengst told me that in many modern and historical Andean groups, “children don't become fully human or "receive their souls" until their first haircut, usually around 2 years of age. So it is possible that the primary infants hadn't gone through this ritual yet and needed extra protection or insurance in the afterlife, given to them by the skulls of the slightly older children.” Because trophy heads are so closely linked to power it makes sense that the addition of a supplementary skull was designed to “underscore or reinforce the connection of the primary individuals and ancestors, deities, or some other aspect of the supernatural cosmos.”

The next question, of course, is where did the extra skulls come from? And what happened to the children they belonged to? The fact that the skulls were so close together suggests that the second skull was in place at the time of burial, but beyond that the situation is very much a mystery. Juengst said that “we can imagine two most likely scenarios: [in the first, the skulls] were preserved and curated from earlier deceased children.” In this situation people were already preserving the heads of children for this or some other purpose when the infants died. This doesn’t seem especially likely, however, because there is very little evidence that the helmet skulls had been handled or polished (like other trophy heads were). The second possibility is that the helmets were deliberately crafted either from other recently deceased children or from children that were sacrificed for this purpose. Juengst said, “the helmets could have been made from children who died more or less contemporaneously with the primary individuals.” All of the remains of the individuals buried at the mound (11 in total) show evidence of disease which suggests that there was either a nutritional crisis in the region or some kind of disease epidemic. As such it’s likely that there were many people dying roughly contemporaneously with one another and it would have been easy enough to modify the cranium from an older child to protect the remains of a younger, more vulnerable one.

All the same, we can’t rule out the possibility of custom-order human sacrifice, said Juengst, because child sacrifice has a precedent in the area. If the older children had been the victims of human sacrifice, though, one would expect to find more evidence of trauma on their remains. But beyond the cutmarks used to make the helmet there’s no evidence of cause of death.

The discovery in Ecuador has provoked a spate of wildly sensationalist newspaper headlines delighting in the gruesome strangeness of the story. To be sure, it’s easy to get carried away by its sensational elements. Dressing the body of one person in the remains of another might sound like something that a serial killer does (in fact, both fictional and real-life killers have been known to do this), but this practice has much more in common with the loving mainstream funerary practices of modern society than fringe homicidal impulses. We still bury loved ones with protective amulets (like crosses), photographs, and favorite items of clothing. We keep locks of hair and ashes of our departed relatives and sometimes wear them on our person. Some people even tattoo the image of a deceased friend or family member on their bodies. And many of us want to be buried close to the remains of their loved ones. None of this strikes us as strange even though we are using bodies to maintain closeness to the dead.

When it comes to children some of the seemingly strange bodily practices of the past—for example massaging children’s bodies into aesthetically pleasing shapes—have modern analogues. Everyone from the Virgin Mary to the 21st century mothers of new-borns swaddle their children. Anthropologist Kristina Killgrove, who first wrote about the discovery in Ecuador, told me that the relatively new field of the study of children in bioarchaeology shows us that “caregivers wanted the best for kids and their community…some past peoples artificially elongated their infant’s heads, while today there is helmet therapy to make kids’ heads more round… Often “strange” past practices make sense within a spiritual context” that was “meant to protect a person or community.”

What’s actually interesting about this discovery is that it provides more evidence that ancient peoples cared for their children, even after death. This wasn’t always believed to be the case. Many historians have hypothesized that high infant mortality rates meant that ancient people were emotionally divested from their children, especially very young ones. The discovery in Ecuador shows that members of the community worried about the status of those children who died before “receiving their souls” and found ways to incorporate them into the community through their burial rituals. What seems gruesome is actually evidence that in the past, as today, people loved their infants and went to great lengths to protect their dead.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies