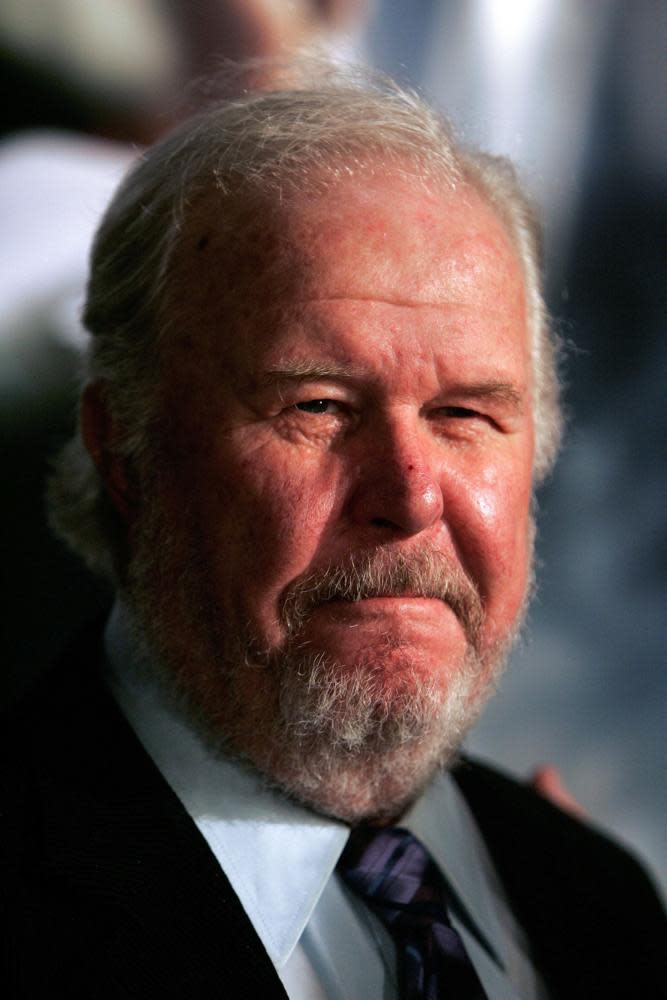

Ned Beatty obituary

American cinema of the 1970s provided an embarrassment of riches for character actors specialising in the eccentric, flawed, vulnerable or monstrous. Each of those qualities was well within the range of Ned Beatty, the self-described “macho-fat-actor-man”, who has died aged 83.

Beatty starred in many of the key films of that decade. He made his screen debut in John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), where he is one of four friends who go canoeing in the Georgia wilderness, only to find that the locals are even more hostile than the landscape. Beatty’s formerly carefree character is raped by a woodsman, who compounds the ordeal by forcing him to squeal like a pig.

He always defended that disturbing scene: “I’m really proud of it. I think it scared the hell out of people.” For that reason, he did not take kindly to being squealed at in the street by strangers. Anyone doing so could expect to receive a curt reply from him, such as: “When was the last time you got kicked by an old man?”

In Robert Altman’s three-hour, multi-character drama Nashville (1975), Beatty is a lawyer and wheeler-dealer unable to connect emotionally with his children, who are deaf. In All the President’s Men, he is Martin Dardis, the Dade County chief investigator who receives a tip-off about the link between the Watergate burglars and the campaign to re-elect Richard Nixon. Network (also 1976) gave Beatty his showiest role, as the boss of a powerful conglomerate who holds forth on the topic of corporate supremacy: “There is no America. There is no democracy. There is only IBM and ITT and AT&T…”

Most of the three-minute speech is delivered from the bottom right-hand corner of the frame, where Beatty is picked out by a theatrical spotlight in the darkened conference room. Part fire-and-brimstone preacher, part circus ringmaster, he rages and gesticulates wildly before making a sudden handbrake turn into the realm of the conciliatory.

The character is a former salesman, a line of work that Beatty knew well: it was his father’s job and, briefly, his own, back when he earned a living selling baby furniture. At the audition for Network, he daringly adopted high-pressure sales tactics, telling the director Sidney Lumet and the screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky that he had another, more lucrative offer waiting for him. “I’m going to walk out of here and I’m going to make a call to my agent,” he informed them. “I’m going to say, ‘Hold on just a little while. I’ll let you know if I want to do that’ and when I come back through the door, I’ve got to know.” He was, he later admitted, “lying like a snake”.

His only Oscar nomination came for Network, and he lost out to his All the President’s Men co-star Jason Robards. But he reached his widest audience as Otis, the dim-bulb sidekick to the arch-villain Lex Luthor (Gene Hackman) in Superman the Movie (1978) and Superman II (1980). The haughty, imperious Hackman and the humble, scurrying Beatty made an endearing comic duo with shades of Mr Toad and Mole from The Wind in the Willows.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Ned was the son of Margaret (nee Fortney) and Charles Beatty. As a child, he performed in a local church choir, and planned to become a priest until he developed a taste for acting after being cast in a school play. He attended Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, without graduating, then spent his early career performing with regional theatre companies.

One of his earliest roles, at the age of 21, was in summer stock as Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. He returned to the part in London in 2003, when he had reached the character’s exact age, of 65. He won great acclaim for that production, as well as for the Broadway transfer (the New York Times commended his “passionate, scrupulously detailed acting”), which brought him a Drama Desk award.

For eight years, he was a resident player at the Arena Stage in Washington. It was there that he appeared in The Great White Hope, which gave him his Broadway debut when it transferred in 1968. Following Deliverance, film came to dominate Beatty’s career. “I’m not one of your actors who bemoans the fact that he has left the theatre,” he said. “For me, film is the more poetic medium, and theatre the more literal.”

John Huston directed him in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) and an electrifying adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood (1979). Beatty reteamed with Burt Reynolds, his friend and Deliverance co-star, for White Lightning (1973), WW and the Dixie Dancekings (1975), Gator (1976), Stroker Ace (1983), Switching Channels (1988) and Physical Evidence (1989).

The disaster movie spoof The Big Bus and the jaunty, would-be Hitchcockian thriller Silver Streak gave him a chance to be straightforwardly funny. Also in 1976, he was a dour hitman in Mikey and Nicky, Elaine May’s grimy tale of small-time hoods.

He featured in two widely maligned films by major directors, Boorman’s Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) and Steven Spielberg’s wartime comedy 1941 (1979). But he sparkled as an FBI agent opposite Walter Matthau and Glenda Jackson in the underrated spy caper Hopscotch (1980); as a corrupt police captain in the smart, sultry thriller The Big Easy (1986); and as the Irish tenor Josef Locke in the whimsical British comedy-drama Hear My Song (1991).

He worked frequently in television, with occasional appearances as the father of Dan Conner (John Goodman) on the sitcom Roseanne between 1989 and 1994, as well as a recurring role in three series of Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-95). Recent films included Mike Nichols’s political comedy Charlie Wilson’s War, Paul Schrader’s brooding thriller The Walker (both 2007) and the British director Michael Winterbottom’s harrowing adaptation of Jim Thompson’s pulp novel The Killer Inside Me. Younger audiences would be hard-pressed to recognise Beatty’s face, though his voice would surely be familiar from Toy Story 3 (also 2010), where he is at first genial, then menacing, as Lotso, the pink, strawberry-scented teddy bear who rules the nursery with an iron fist.

Beatty was happy to stay under the radar. “Stars never want to throw the audience a curve ball, but my great joy is throwing curve balls,” he said in 1977. “I love it when audiences don’t recognise me from movie to movie, when they see Network and don’t realise I’m in it until the final credits. It means I’ve done my job well.”

He is survived by his fourth wife, Sandra Johnson, whom he married in 1999, and eight children. Three earlier marriages – to Walta Chandler, the mother of Douglas, Charles, Lennis and Wally, in 1959; Belinda Rowley, mother of John and Blossom, in 1971; and Dorothy Lindsay, mother of Thomas and Dorothy, in 1979 – ended in divorce.

• Ned Thomas Beatty, actor, born 6 July 1937; died 13 June 2021

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies