Nepotism, morphine and secret homoeroticism: The bizarre history of Universal’s movie monsters

There’s nothing new under the sun, especially not in Hollywood. The recent wave of reboots, remakes and revivals seems to show no sign of stopping. The Invisible Man, based on HG Wells’s novel and the 1933 Universal movie starring Claude Rains, is the latest film to update an iconic property.

Elisabeth Moss now plays a woman haunted by an abusive ex-boyfriend, who has become her invisible stalker – turning the monster into a symbol of toxic masculinity for the #MeToo era. The original Invisible Man was a more straightforward mad scientist, and once part of the Universal movie monster line up that included Dracula, the Wolf Man and Frankenstein. The studio’s own sequels and reboots created the concept of iconic characters showing up in each others’ films long before Avengers: Endgame marketed itself as the “most ambitious crossover event in history”.

It all began with a man named Carl Laemmle, or “Uncle Carl” to his employees. As founder and president of Universal Pictures, he oversaw the studio’s early years, and made hundreds of horror classics, including The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931). Laemmle was also legendary for his nepotism. He ensured his son, Carl Jr, would succeed him at the studio, and promoted his nephews to executive positions, which prompted the poet Ogden Nash’s two line ode: “Uncle Carl Laemmle/ Has a very large faemmle.”

The signature Universal style was heavily influenced by German Expressionism, thanks to the German-American Laemmles, who employed filmmakers from their homeland such as Karl Freund, the cinematographer for Dracula. Looming angular sets and nightmarish lighting made these monster movies as visually striking as Expressionist classics The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922).

This stylistic choice made even their romantic melodramas like The Man Who Laughs (1928), which was directed by the German Expressionist filmmaker Paul Leni, look like a horror film. Joaquin Phoenix wouldn’t have won his Oscar this year if not for Conrad Veidt’s titular carnival freak character, Gwynplaine, since the creators of Batman’s nemesis the Joker in 1940 were directly influenced by the image of Veidt’s character, who was disfigured with a permanent grin.

Lon Chaney became the studio’s first star in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), cementing his reputation as the “Man of a Thousand Faces”. His skill with makeup, as well as his affinity for pantomime as a child of deaf parents, allowed him to transform physically into his silent film roles. He brought a degree of sympathy to “monsters” like The Hunchback of Notre Dame‘s Quasimodo. When he died in 1930, his son Creighton, billed as Lon Chaney Jr, followed in his father’s footsteps to become an actor too, playing the Wolf Man in multiple films for Universal.

Frankenstein and Dracula launched the careers of two struggling middle-aged foreign actors – Hungarian stage actor Bela Lugosi and Anglo-Indian Boris Karloff.

Lugosi was fond of mentioning his past as a respected actor in his homeland, regardless of how accurate that was. It’s certainly true that he had to leave Hungary in 1919 because of his activism in the actors’ union, after the country’s failed Communist uprising. Eventually Lugosi found his way to Broadway as Dracula. A kind of Robert Pattinson of his time, Lugosi attracted many female admirers through the role, including the “It Girl” of 1920s Hollywood, Clara Bow. After the film version, however, he resented how the role led to him being largely typecast for the rest of his career. His strong accent didn’t help, and over the years he ended up in more and more B-films.

Boris Karloff had acted in 80 films before being cast in a role Lugosi had rejected: Frankenstein’s Monster. His name was left off the credits in favour of a question mark as a promotional gimmick, and he wasn’t well-known enough to be invited to the premiere. He was looked upon as more of a human prop than a serious actor. No one could have predicted that the 43 year old would become a star – not least because he had no dialogue, and looked unrecognisable after four hours in makeup every day. But “the dear old boy”, as Karloff referred to the monster, kicked off a long career as a horror star.

They tried to cast Karloff in The Invisible Man as well, but pay disputes allowed British-American actor Rains to step in and deliver an implausibly impressive breakout performance as a character whose face is only seen for half a minute.

Even though the perspective has now shifted from the “man” himself to one of his victims in the 2020 reboot, it’s not the first alternative take on the classic. Universal came up with the gender-swapped sequel The Invisible Woman and the war propaganda film Invisible Agent during the 1940s.

All of the more successful Universal films inspired sequels, of varying quality. Unanimously considered one of the best sequels in cinema history, and probably one of the best monster movies, was Bride of Frankenstein (1935). James Whale, who had also directed the first Frankenstein and The Invisible Man, lived openly as a gay man. This has led to film scholars reading homoeroticism into the sequel he directed, where Dr Pretorious (played by Ernest Thesiger) tempts Dr Frankenstein away from his wife to create another unnatural life form.

Whale’s inspiration for the Bride was Maria, the female robot from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). Elsa Lanchester’s towering black and silver hair in Bride of Frankenstein became one of the most timeless images in horror, and her character allows for a more sympathetic take on the central creature than the first film. The Monster doesn’t speak in the original Frankenstein, but him learning to talk undeniably lends pathos to the character in this sequel, when he poignantly tells Dr Pretorious “I want friend like me.” By giving him a voice, Whale transformed the Frankenstein story into a paean to the outsider.

Although the Laemmles were ousted from Universal a year after Bride of Frankenstein, the success the studio had experienced in the 1930s allowed Uncle Carl to take on a heroic cause. He sponsored hundreds of Jews from his home town of Laupheim and Württemberg, paying both emigration and immigration fees to ensure they escaped Nazi Germany. Laemmle also used his contacts in the House of Representatives to ensure and facilitate immigration to the United States for those fleeing the Holocaust.

A decline in Universal’s horror output after the Laemmles’s departure led to undeniably gimmicky films like Son of Frankenstein (1939), which united Karloff and Lugosi and made the Monster mute again. Sequels had a tendency to forget developments, or resurrect characters from the previous film. Crossovers like Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), Son of Dracula (1943) and House of Frankenstein (1945) combined the studio’s star monsters in increasingly contrived plots to try and recapture the public’s attention. Eventually, producers turned to another genre altogether: comedy.

The comedy duo Abbott and Costello had been working in films since 1940, and became a guaranteed box office draw over the course of the decade. When they made Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), Lou Costello hated the script, and allegedly said his five year old daughter could write better jokes. There was trepidation about bringing back Lugosi as Dracula and Chaney Jr as the Wolf Man in this comedy. But audiences disagreed with Costello, flocking to a film where the humour and the horror both had room to breathe.

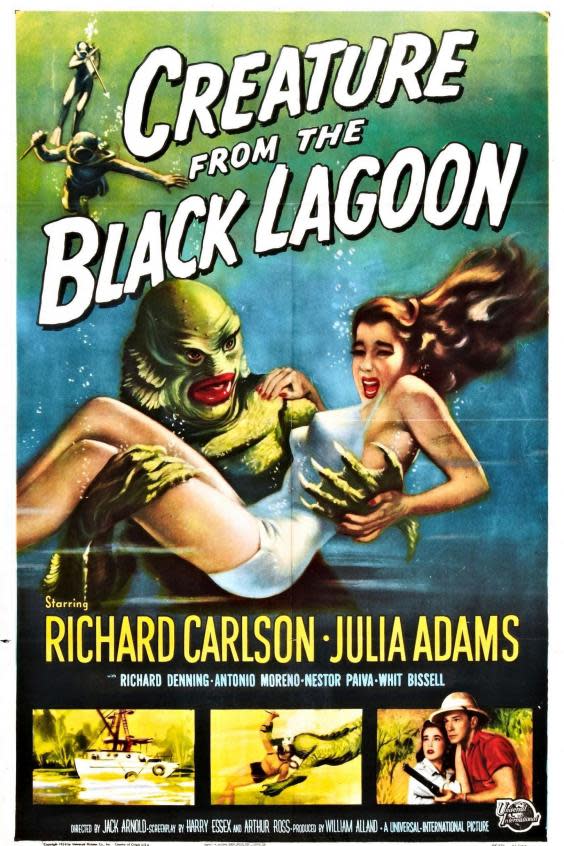

This success kicked off a series where Abbott and Costello met the Invisible Man, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and the Mummy, with diminishing returns. Monster movies were on their way out, but producers were determined to flog the comedy-horror horse until it couldn’t be mistaken for alive anymore. Universal managed to produce one more classic movie monster in the Fifties – Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) – and dabbled in 3D technology. But the end of the monster movies era was more of a whimper than a bang.

Universal’s stars went their separate ways in the following decades. Chaney Jr stayed busy in supporting roles, and branched out into television. In a 1952 live television version of Frankenstein on the anthology series Tales of Tomorrow for which he allegedly showed up drunk, Chaney played the Monster. Apparently under the impression that the live broadcast was just a rehearsal, he would pick up furniture that he was supposed to violently smash, and instead carefully place it back down while muttering, “I saved it for you”. He also revisited the roles of the Wolf Man and the Mummy for television series Route 66, before his death in 1972.

Lugosi, by now severely addicted to methadone and morphine, was living in obscurity and near poverty when one of the most infamously terrible directors of all time decided to champion him. Ed Wood, the Tommy Wiseau of the 1950s, used Lugosi in the low-budget flicks Glen or Glenda, Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space. These Z-movies would eventually inspire a cult following when they were rediscovered in the 1980s, thanks to the atrocious special effects and nonsensical plots. Martin Landau also won an Academy Award for his portrayal of Lugosi in Tim Burton’s film Ed Wood (1994). Lugosi wouldn’t live to see this wave of interest in his later work, however. After dying of a heart attack in 1956, he was buried in one of his capes from Dracula, in tribute to his most famous character.

Karloff was luckier than his old co-star, and worked consistently until his death in 1969. He showed up often in films by Roger Corman, the indie genre film producer who launched the careers of Francis Ford Coppola, Jack Nicholson and Martin Scorsese, among others. He also narrated the classic Dr Seuss cartoon How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Karloff, who suffered from emphysema, only had half of one lung still functioning while he performed his final roles, and required a wheelchair and oxygen between takes. He died of pneumonia in England at the age of 81.

If we now think of the monster characters as iconic titans of the silver screen, that’s a testament to the power of Hollywood’s self-mythologising. In fact it wasn’t until channels like WABC-TV began playing Universal monster movies late at night in the late Fifties, and Maila Nurmi introduced them as the campily glamorous horror host character Vampira, that they gained their legendary status.

These late night marathons created a new generation of fans, and the films’ relevance resurged. Director Guillermo del Toro became one of those fans when he saw Creature from the Black Lagoon at the age of six. He tried to make an official reboot of the Universal series but was rebuffed: “I went to Universal and I said, ‘Can we do the movie from the point of view of the creature?’ They didn’t go for it. I said, ‘I think they should end up together.’ They didn’t go for that, either.”

Instead, he made The Shape of Water, which won the Best Picture Award at the 2018 Oscars. This subversively romantic take on a movie monster was far more critically acclaimed than Universal’s own hamfisted attempt at re-launching their own franchise, The Mummy (2017). The Universal film starred Tom Cruise and Russell Crowe, and was intended to be the first of a series called the “Dark Universe”. Audiences rejected the pulpy reboot, however, and a slate of films (including Johnny Depp as the Invisible Man) was cancelled.

This latest woman-centric spin on The Invisible Man will provide a far different take from Rains in 1933, and won’t include the stylistic German Expressionist sets or lighting that once defined a Universal film’s look. But as the studio’s history proves, the original monster movies were constantly reshuffled, reinvented and written into crossovers to suit changing tastes. The story of Universal classic monsters is one of reinvention. And if Carl Laemmle could see his characters’ new lease of life 87 years on, we can imagine he’d toast it like Dr Pretorious in Bride of Frankenstein: “To a new world of gods and monsters!”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies