Paddy Considine interview: 'Sometimes I don’t want to do this anymore' (exclusive)

Paddy Considine has been on quite a journey, man.

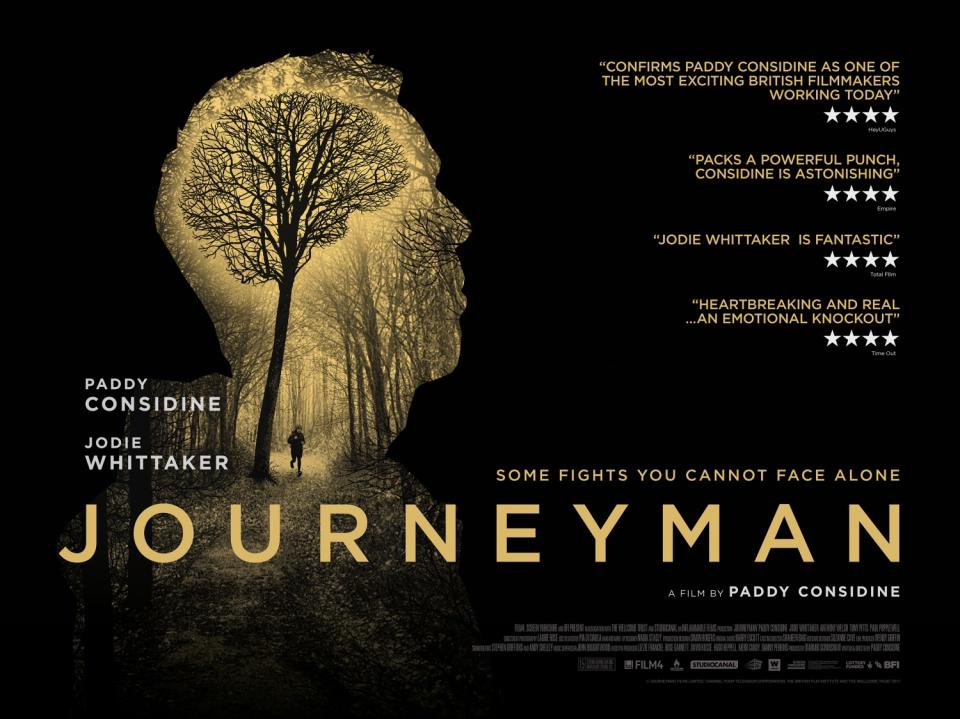

After announcing himself as a major directing talent in 2011 with his stunning debut Tyrannosaur, it’s taken seven years for the Dead Man’s Shoes star to get his second directorial effort Journeyman into cinemas. (Journeyman is out now on Blu-Ray, DVD, Digital download and VOD along with exclusive new extras.)

It might have happened sooner had life not got in the way, Considine explains to Yahoo Movies, as the project – about a champion boxer who suffers a brain injury – was first greenlit for development by the BFI back in 2009.

Journeyman went to the bottom of the pile while Considine developed his BAFTA-winning short Dog Altogether into the full-length Tyrannosaur, which he then hoped to follow up with an adaptation of Jon Hotten’s true-life crime drama The Years of the Locust.

After several visits to America, where Considine hoped to shoot Locust with a cast of unknowns, it gradually became clear that the adaptation was more ambitious than they’d originally hoped.

Unbeknown to Paddy though, he had a much bigger battle on his hands than those he was having with film financiers.

“In my 30s, I sort of came to a bit of a standstill with a lot of things,” Considine explains to Yahoo.

“I realised that I was going inwards into myself. I was becoming more detached from everything and everybody around me. And there were many factors to that.”

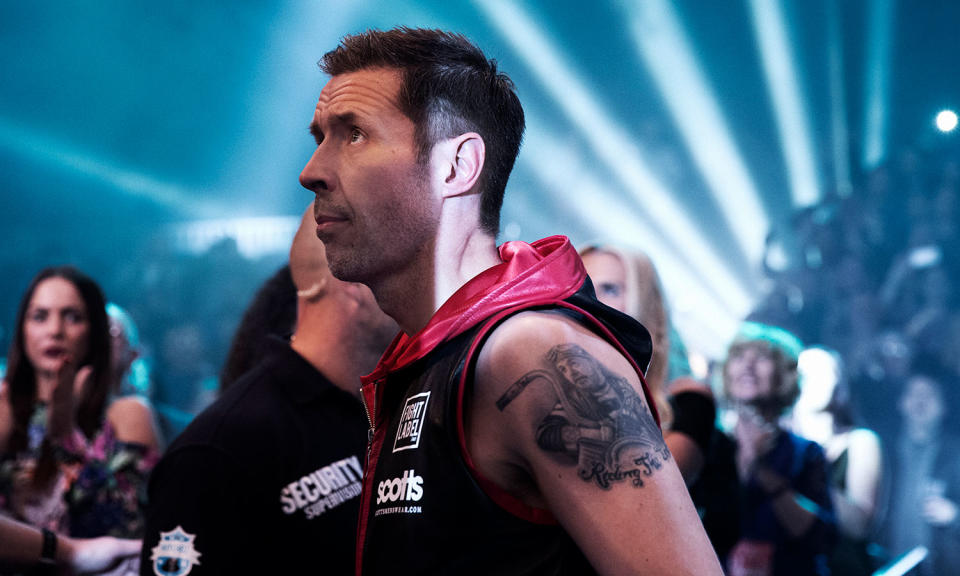

One of those factors was being diagnosed with mild Aspergers in 2010, and then in 2013 with a rare cognitive condition called Irlen syndrome. When Yahoo meets Considine to talk about Journeyman, which brilliantly eschews the usual macho trappings of the genre, the Burton-born actor greets us wearing tinted sunglasses.

The tint helps the actor to live with Irlen syndrome, a condition he admits left him feeling “inward, volatile, angry” and eventually led him to drink. The parallels with Paddy’s story and Journeyman are clear, but the filmmaker is quick to stress his journey to living with his conditions is far removed from those who’ve suffered brain trauma like his character Matty Burton.

Like Matty, Paddy is a humble presence, who suffers the same doubts and insecurities as we all do. Despite being a filmmaker with legions of fans he admits that he sometimes thinks about packing it all in.

“I have good and bad days, like anybody,” he says. “But sometimes I don’t want to do this anymore, then other times I go ‘well, you’re just ridiculous’. You have a bad day and you’re screaming out for help, or you’re going ‘I never want to do this ever again’, but the truth is i’m compelled to do it. There’s nothing else I know how to do. I do this. It’s what I do.”

Thankfully Paddy plans to get behind the camera sooner rather than later, and while he continues to develop Locust, he says he has another original idea up his sleeve.

“Whether I like it or not, there’s another story brewing up inside of me, so I’m going to have to go and do it, or it won’t leave me.”

Here’s our full interview with Paddy Considine where he talks about the themes of Journeyman, how he researched the role and got into shape, and how he deliberately set out to avoid boxing movie cliches.

Yahoo Movies: You first struck a development deal for Journeyman in 2009, how much has the film changed since then?

Well, it’s still the same premise. Even back in 2009 it was about a fighter that suffered a brain injury. That’s the proposal that we put in, but what happened was I made my film Dog Altogether and that became Tyrannosaur.

So Tyrannosaur became the project and Journeyman was put on the back-burner a little bit. Then after I made Tyrannosaur, we optioned a book called The Years of the Locust, and we still have them, we’re still trying to get it made.

But after several failed visits to America, because it’s an American story, I realised it was just going to take too much money to make it, and the way that I wanted to make it… I didn’t want to cast stars in it, and you’re not going to get those millions if you don’t have name attached, so I was just after a few years of back and forth, I thought all these years have gone by and I haven’t made my second film because I’ve been trying to get this off the ground.

So I went back and looked at Journeyman again, and thought maybe I should revisit this. I’d spoke to a friend about it years earlier – a writer called Geoff Thompson – and he said ‘What happened to your film about the boxer? That was great.’

So I was like ‘Yeah!’. Life just has a strange way of pointing you towards the stories you should be telling, oddly. So I’d been distracted for too many years trying to make the film in America and getting nowhere.

So it felt good to come back home in a way.

In the press notes for Journeyman you describe the film as being ‘oddly biographical’, but it seems to me that it’s about things that you may have been through since you first got the development deal?

It’s difficult calling it autobiographical, because it’s a little bit insulting really. I haven’t suffered a brain injury and I don’t want to insult people who’ve been through that trauma, you know? Because it’s not autobiographical in that way.

It’s a really weird way to describe it. When it’s in the press notes, you think it shouldn’t really be there. Brain injury in a boxing ring is a real event. But if you’re writing a piece of fiction around that, some part of you has to make its way into that story. It just does.

And the only thing that I could identify with, was some sort of transformation within yourself, with something happening to you. I realised that in my 30s, I kind of, sort of, came to a bit of a standstill with a lot of things.

I realised that I was going inwards into myself. I was becoming more detached from everything and everybody around me. And there were many factors to that.

One of them was that I’d been diagnosed – in inverted commas – with mild Asperger’s. Something that you would have all your life. But then I discovered I had this condition called Irlen syndrome, which is scotopic sensitivity. It’s basically how your brain processes light.

What happens is that if there’s too much visual information in front of me, like all the patterns in this room, without these glasses [takes off tinted glasses], they will start to overwhelm my brain and after a while, I will struggle to concentrate on you because of all the patterns, and then I won’t make eye contact with you, and then I’ll get confused in my head, and that led to me feeling inward, volatile, angry.

The only way I could deal with that was through using alcohol. I was in this vicious cycle without actually knowing what was wrong with me. So I was just disappearing. I had to recover from that.

Luckily I found myself in a situation where I was sitting in front of somebody who could identify that I had this condition, because it’s very rare.

So I went to America in the end, to meet Helen Irlen who had discovered this thing, and pioneered these glasses that I have to wear. So I was tested and got my tint over there. But I was on a fast-track to a really dark place.

So I think the only thing in Journeyman, I suppose, is just that sort of idea of somebody that has to come to terms with their limitations, and their conditions, that’s all it was. Because the condition would make me feel very anxious and very trapped, and it was very frightening and uncomfortable at times to be honest.

One thing the film made me appreciate is how much, as a man, I rely on a lot of other people to enable me to live my life. After seeing the film I had to tell my wife just how much I love her, and appreciate everything she does for me and our child. Is that a place you found yourself too?

Well, I’ve got very few friends. It’s a very small circle of people around you that truly love and care about you, you learn. Especially when you’re down on your ass. That’s where you learn who the true people are in your life. I’m lucky that I have a very core amount of people around me that are there that I can call upon for help, and I feel a certain way.

I have the love of my wife and children and friends that go back to my teenage years, but they’re a very small circle of people. What the film is saying at that point with Matty left alone, in the film – metaphorically speaking… well, actually speaking – he has to face himself and come to terms with who he is.

One of the things we do as human beings – yeah, we rely so much on other people around us, and it kind of defines who we are. We rely so much on them that people become our rocks and our foundations, and I was thinking in my head that that’s kind of unfair. It’s an unfair thing to do to your loved ones.

People fail. People break down. People let you down. Because we’re just human beings after all. But in the film, Emma [Matty’s wife, played by Jodie Whittaker] was there to pick up the pieces and look after him, but also by being there she was stopping him, almost stunting his spiritual growth, his cognitive growth.

So she has to leave after that certain episode where she can’t take any more of his behaviour, and he has to face himself, he has to come to the realisation of who he once was, and he has to accept who he now is.

I had to find a way within the writing to get her to a point where she had to clear, so he could grow spiritually and take on the next chapter of his life.

The film inspired me to watch Johnny Harris’ Jawbone which is now on Netflix. You two mix in the same circles, having both worked with Shane Meadows – did you swap notes?

Well no. It doesn’t really work like that. They’re two totally different films. Johnny is a beautiful man. Actually Johnny sent me a version of Jawbone, probably a year before they started filming it, and I read it, and all I knew was that it was a very different film to the one that I was trying to make.

I’m really pleased for Johnny because it’s not easy getting a film made. And I knew how much Jawbone meant to him. That was a personal film for Johnny, and he’s a beautiful man. So it’s testament to him that Jawbone’s had the success that it has.

I didn’t look at boxing films for inspiration, if anything you don’t want to watch other things, because you create this other little world of your own. A lot of boxing films, a lot of other boxing films that I’d seen, just dealt so much with masculinity.

It was about men fighting their inner demons. And I was like ‘I don’t want Journeyman to be about that’. It’s not about inner demons. He’s an athlete who’s good at what he does, who gets injured, and then the trouble begins, because this guy’s not responsible for his behaviour. He has no cognitive controls.

I thought the interesting thing about Journeyman is that it was something that had never been explored before. It was territory that had never been explored. And after Tyrannosaur and other things that I’d done in the past, I just wanted to get away from that idea of masculinity.

It started to be about anger, and people dealing with these inner turmoils, and it started to become boring to me as a subject to make a film about.

Do you feel like there’s a connective thread between this and Tyrannosaur, thematically?

Yeah. I think they’re both about men that need to be rescued.

I discovered it the other day. I was driving along the other day and it occured to me. I think about those films, and in Tyrannosaur, Peter Mullen’s character [Joseph], as far as I was concerned when I wrote it, was somebody that has a spiritual awakening.

Not a religious awakening, a spiritual one. When he meets Olivia Colman’s character [Hannah], and he makes assumptions about the world that she’s from, and he’s wrong. The two people from two different sides of society, from two different class divides, who actually are soulmates really. She’s safer with the most dangerous man in the film because he’s fallen in love with her, profoundly.

And that’s what I wrote in there: this man cannot understand what’s going on in his body, because he’s had some kind of awakening, and he’s fallen in love.

The same thing with Journeyman, it’s this heroic man, who the one thing after his injury that motivates him, is to get his wife back. The love of his life, back in to his life.

So I think that’s probably it. They’re both about men who need saving by women. And as I drove along I thought ‘what’s that saying about me?!’

With the writing, directing, and acting… and the physical training, then the physical nature of your performance of Matty post-injury, did you ever think: ‘I’ve bitten off more than I can chew?’

Not once I’d started. It’s a good old thing, the mind, it’ll trick you and tell you can’t cope, and not to do it, and ‘what are you thinking? You’re an egotistical pig’ and all these things. That inner demon will tell you every reason not to do it. It’s never the right reasons, because the only reason is fear.

I thought ‘well, is it just pure vanity?’ and I thought, ‘every performance is vanity, don’t do it if it isn’t’. My thoughts about taking it on were greater than actually taking it on. Once I’d began training to be Matty the fighter, it was fantastic.

My boxing training shaped the way I approached shooting the film. I took to the training. It was difficult at times. The diet was more difficult than the training, because it messed with your head a bit. But I absolutely loved it, it got me regimented, it got me in line.

I was aligned enough to then go into the film and my head was clear, and I had this fantastic approach to filming.

But all the boxer side of it spoke for itself. There’s no revelations there. But the side of playing Matty, the version of Matty who was injured, yeah, that was different.

I didn’t really know fully until the moment I turned over on him at the hospital, how I was going to play it. I kind of had some idea, and I’d auditioned myself months before and done an audition tape with Paul Popplewell [who plays Matty’s trainer Jackie], to see if I could do it. And there was a version of it in there, but I did not rightly know how I was going to do this until that very moment.

And what happened in that moment was that all the research I’d done at Headway [the brain injury association] in Henley, and all the people that i’d met with head injuries, all of that research that you do just came into play. Because the film really is about the recovery, it’s not about the penultimate fight.

His fight is the get his cognition back and his family back. So, it’s almost like in those final moments, that’s when the character was born, literally, when we said ‘action’ and it happened.

Will you direct another film?

I will.

Ask me tomorrow and i’ll say I’m not. I want to be as far away from it as possible. I have good and bad days, like anybody. But sometimes I don’t want to do this anymore, then other times I go ‘well, you’re just ridiculous’. You have a bad day and you’re screaming out for help, or you’re going ‘I never want to do this ever again’, but the truth is i’m compelled to do it. There’s nothing else I know how to do.

I do this. It’s what I do. Whether I like it or not, there’s another story brewing up inside of me, so I’m going to have to go and do it, or it won’t leave me.

Are there any filmmakers you look to and think ‘i’d like a career like that?’

Well, I got out of that trap a long time ago, because I realised – even as an actor – you can’t compare your career to other people’s. If that was the case, I’d be like John Cazale or Daniel Day Lewis, there wouldn’t be a single piece of shit on my CV, you know? They’d all be… i’d be knocking them all out of the park, but that’s not the reality for every actor.

You’ve got to take the rough with the smooth, and I felt like that as a director. I admire directors’ work, and there’s certain directors that I really, really do admire greatly, but nobody’s career path.

You’ve just got to do your own thing, and I think once you start comparing yourself, or putting yourself in competition with other people, you’re in trouble because it can only lead to failure really.

The limitations start and end with you. Stories: that’s all i’ve got to do. Tell my stories.

If I could paint. I would paint. I wouldn’t do this. If it did it, if it shifted it all, I’d paint it in a picture. But it doesn’t. I can’t even write my own name, so I have to do this I guess.

Journeyman is out now on Blu-Ray, DVD, Digital download and VOD along with exclusive new extras.

This interview was first published on 27 March.

Read more

Simon Pegg on why Star Trek 3 flopped

Jack Whitehall gets Hollywood break

Bella Thorne on her post-Disney struggles

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies