The Penguin Lessons review – Steve Coogan and feathered friend dip into 70s Argentina

Films set in Latin America during periods of political and social unrest – the early work of Pablo Larraín, say – have traditionally been low on Dead Poets Society-style inspirational uplift. Or, for that matter, penguins. Now the Steve Coogan Heartwarming True Story Machine – the same one which produced Philomena and The Lost King – seeks to rectify the oversight, and not a moment too soon.

Related: Hard Truths review – a Mike Leigh classic of day-to-day disillusionment and courage

This adaptation of Tom Michell’s cosy memoir The Penguin Lessons, scripted by Coogan’s semi-regular collaborator Jeff Pope and directed by Peter Cattaneo (The Full Monty), begins in Buenos Aires in 1976, just as Isabel Perón is being ousted in a military coup. Tom, played by Coogan, pitches up with his wardrobe of snazzy beige and mustard-coloured jackets (“Steve Coogan’s suits by Gresham Blake”) at a private school where he will be teaching English to the city’s most privileged teenage boys. A harrumphing headteacher (Jonathan Pryce) is on hand to explain the noises – “Argentina is in chaos!” – and to remind Tom to approach politics with a small “p”. It’s a lesson the film-makers embrace with gusto.

At first, the kids aren’t alright. Paper aeroplanes whizzing through the air, pins on teacher’s seat, that sort of thing. Then again, Tom’s heart isn’t in it either: he skives off to nap in the garden, where he overhears the maid Sofía (Alfonsina Carrocio) remonstrating with the revolutionary fishmonger. It’s his politics which are revolutionary, that is, not his fish.

Tom vows to stay out of all that until one morning when a woman he is trying to impress cajoles him into rescuing a Magellanic penguin stranded on the beach in an oil slick. He hoses it down and then the blighter won’t stop following him. Before long, it not only has a name (Juan Salvador, after the Spanish version of the hippy-dippy bestseller Jonathan Livingston Seagull) but it is living in Tom’s bath and becoming a confidant to everyone at the school. Having told himself “there’s nothing we can do” when he first encountered the stricken bird, he wakes up to the fact that – hey! – one guy can make a difference. Inspired by his relationship with Juan Salvador, Tom becomes the mouse that roars, or at least raises its voice every now and then.

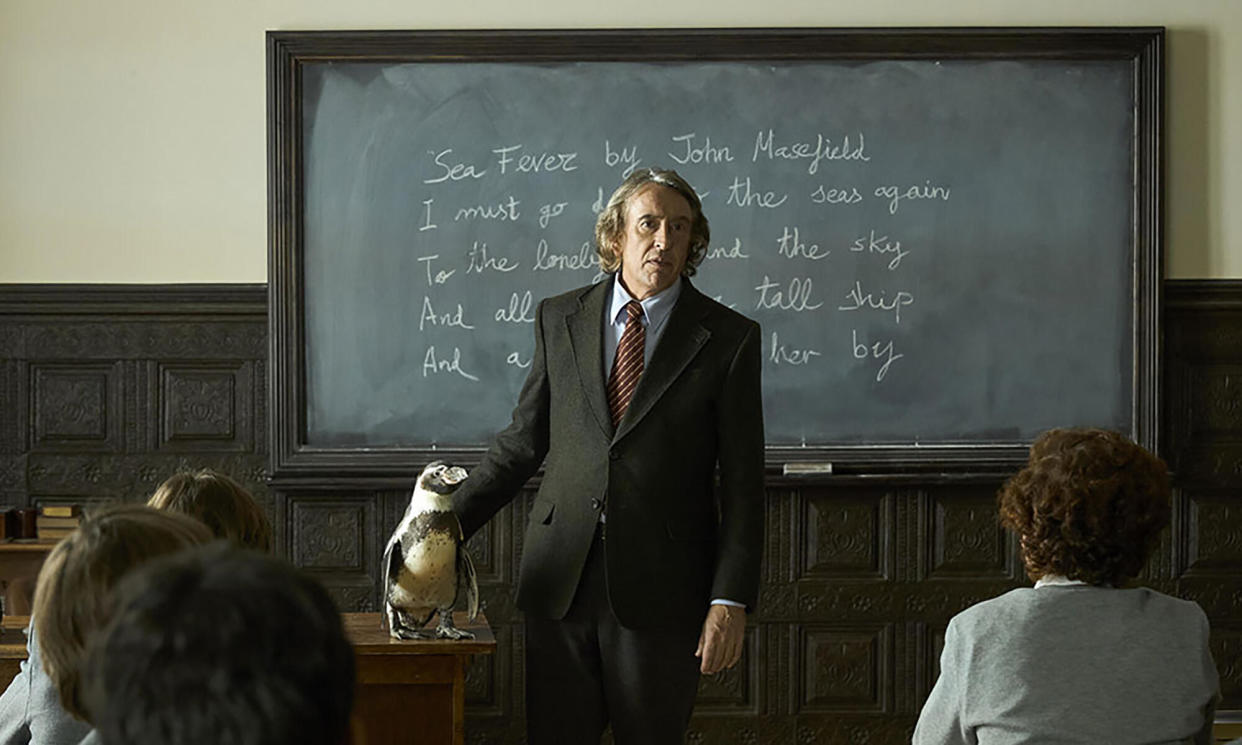

Before you can say “O Penguin! My Penguin!”, he is inspiring his pupils to lie beneath their desks to see life from another perspective, using poetry to teach resistance – cue more harrumphing from the school head – and even standing up to a military bullyboy.

It’s understandable that a film this gentle wouldn’t venture into the gory details of what happens to Tom during a bruising night in the cells but to gloss over any of the terror a civilian might have felt under the cosh is baffling. “You should see the other guy” is as close as it gets.

There is a glass-half-full approach and then there is submerging reality so deeply in whimsy, sentimentality and cultural cliche that it needn’t be there at all. Anyone familiar with the book will be grateful for the small mercies of Pope’s script, which omits the penguin’s interior monologue and jettisons a scene in which Tom’s shyest pupil swims triumphantly alongside Juan Salvador in the school pool. Then again, readers didn’t have to endure Federico Jusid’s score, with its bandoneon, piano, classical guitar and click-clacking guiro drenching every scene like an oil-slick.

It’s no surprise that Coogan displays precision comic timing, or that his scenes with the wonderful Björn Gustafsson, as an ingenuous colleague baffled by irony and sarcasm, are a delight. The film might have made a winning buddy movie between the two of them, if only that blasted penguin wasn’t constantly muscling in with its quizzical reaction shots. When it comes time for Tom to divulge the tragedy in his past, however, the upper register of emotion available to a Bill Nighy figure continues to elude Coogan.

Isona Rigau’s production design has a zingy authenticity – the azure-and-orange tiles in a hotel bathroom evoke an entire decade – and Xavi Giménez’s cinematography lends the locations (Argentina, Uruguay, Gran Canaria) a dreamlike magic. There’s not much to be done, however, with a film so conflicted that it can end on a title card acknowledging that 30,000 people were killed or disappeared, and still be described as “feelgood”.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies