‘Peter O’Toole could have been killed – it’s a pity he wasn’t’: inside Lawrence of Arabia’s hellish shoot

Towards the end of the first half of Lawrence of Arabia, a dusty and dejected TE Lawrence, fresh from battling his way across the Sinai desert, is confronted by a motorcyclist across the Suez Canal. The rider calls out: “Who are you?” As Lawrence looks at him with a mixture of confusion and fear, it is clear that TE Lawrence – archaeologist, scholar and warrior – no longer has any idea who he is.

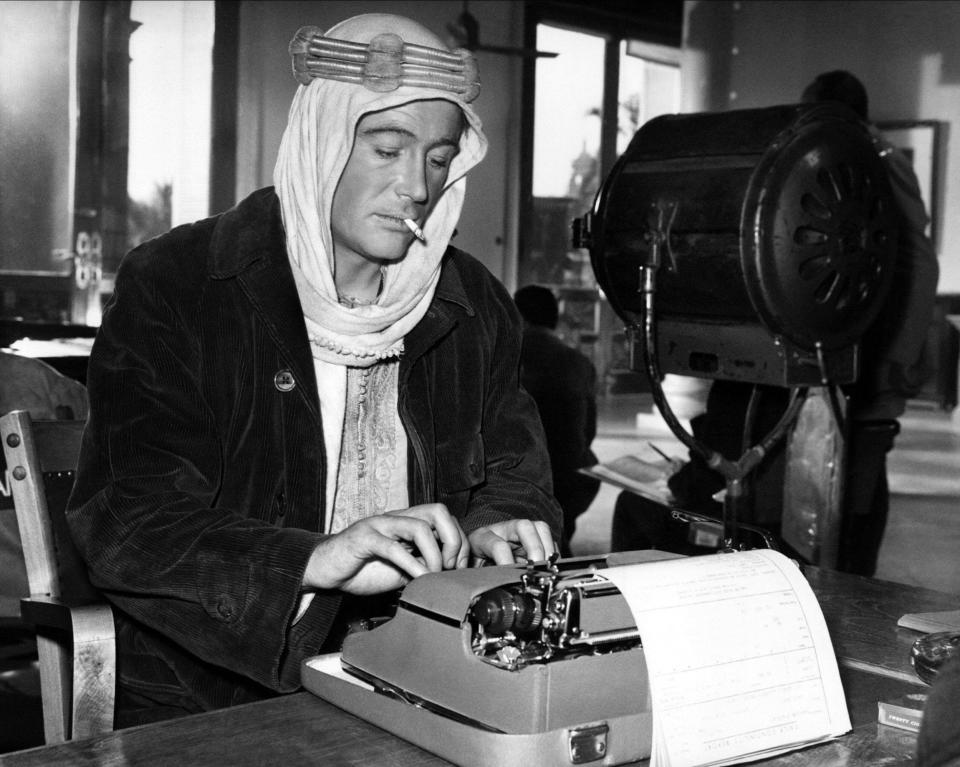

Yet much the same could be said of the actor who played Lawrence, Peter O’Toole, who underwent one of the longest and most gruelling shooting schedules in cinematic history. By the end of the shoot, he barely knew who he was, either.

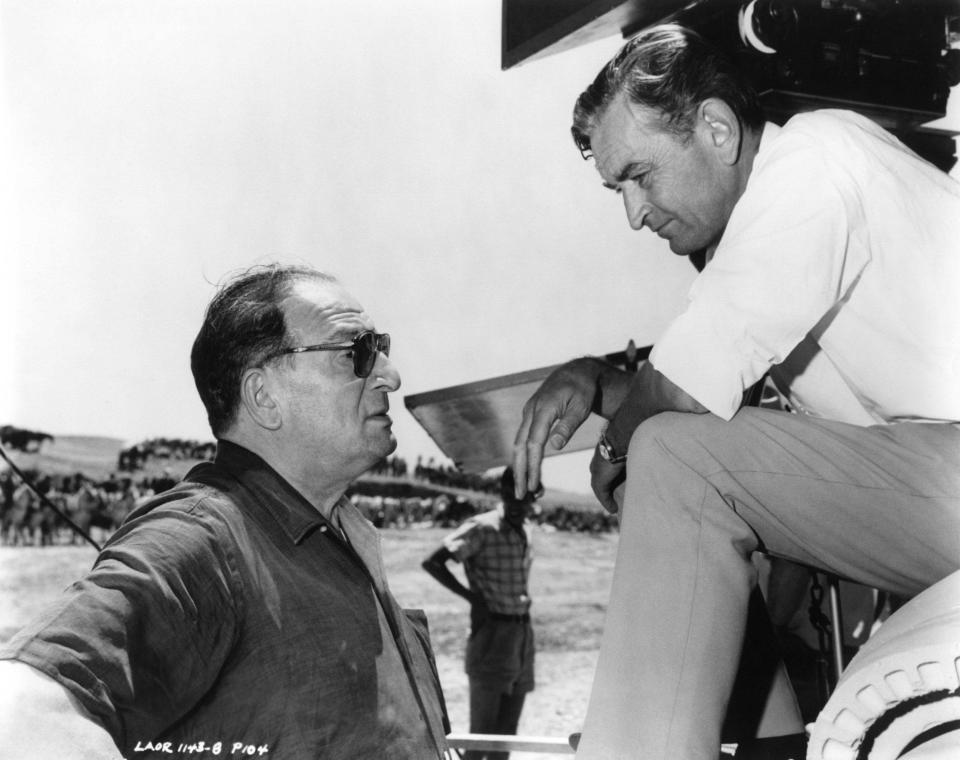

At the time of his casting, aged 28, O’Toole had had a successful first season with the RSC at Stratford, and had appeared in small parts in a few undistinguished films. Yet Lawrence’s director David Lean had seen him play the debonair Captain Monty Fitch in the 1960 caper film The Day they Robbed the Bank of England, and declared afterwards “I’ve got him!”

Producer Sam Spiegel wasn’t sure. He had had previous form with O’Toole, who had ruined his screen test for Spiegel’s picture Suddenly Last Summer, apparently on a whim. Playing a brain surgeon, O’Toole had turned to the camera and said: “It’s all right, Mrs Spiegel, but your son will never play the violin again.” Not only did he not get the part, but Spiegel’s reaction to Lean’s intention of casting him was to say: “I tell you, he’s no good. I know it.”

O’Toole was paid £12,500 for the role. It was a pittance for a leading man – the supporting actor Jose Ferrer was paid double the amount – but a fortune for the as-yet-unknown actor. As soon as he accepted it, he had to extricate himself from an agreed season with the RSC, causing permanent enmity between him and the then-artistic director Peter Hall, and then headed out to Jordan, where the film was to be shot, in early 1961. The notoriously hell-raising actor, who had already acquired a reputation for heavy drinking and unreliability, arrived in the country deeply hungover and was given a talking-to by Anthony Nutting, a former diplomat who served as the film’s technical advisor. “You’re the only actor we’ve got for Lawrence,” Nutting told him. “And if you get bundled home, that’s the end of the film, and that’s probably the end of you.”

O’Toole took him at his word, immersing himself in the character of Lawrence. He spent months doing everything from learning to ride a camel to staying with Bedouin tribespeople, all under scorching heat that made normal movement near-impossible. Lean encouraged this dedication, telling O’Toole: “Physical discomfort is the price of authenticity.” That Lean had his air-conditioned Rolls Royce shipped over to the desert at huge expense does suggest that his own commitment to this discomfort was less authentic than that of his leading man.

When production began on 15 May 1961, Lean deliberately put the actor through dozens of takes in the extreme heat with the aim of “knocking the wind out of his sails”, and refused to praise his performance. This drove O’Toole to despair; underneath his bravado and charisma, the actor was deeply insecure about his first screen leading role, and believed he was incompetent. One evening, angered by what he saw as his limitations, O’Toole punched the window of a caravan, cutting himself badly.

Eventually, it became obvious that filming in Jordan, miles away from civilisation, was impractical. The cast and crew were beset by frequent outbreaks of dysentery and scarlet fever, often resulting in actors being unavailable for shooting in what was becoming an increasingly unwieldy production schedule. Accordingly, in December 1961, filming switched to the more manageable surroundings of Spain.

O’Toole celebrated the move to Europe by getting wildly drunk, and subsequently he was a far less malleable presence. Alec Guinness, who played the wily Prince Faisal, had been impressed by him initially, writing in his diary: “[O’Toole] has great wayward charm and is marvellously good as Lawrence. He’s dreamy good to act with and has great personal charm and gaiety.” But seeing this gaiety up close in Spain was a less enjoyable experience. After O’Toole drunkenly misbehaved at a party and threw a glass of champagne in his host’s face, Guinness wrote: “Peter could have been killed – shot, or strangled. And I’m beginning to think it’s a pity that he wasn’t.”

By this stage of production, O’Toole was increasingly restless, and given to outrageous ad libs. One of the crucial scenes in the film comes when Lawrence is kidnapped and flogged by the Turkish Bey: it is loaded with homoeroticism, and the implication is that the sexually ambivalent Lawrence was raped. When O’Toole and Jack Hawkins, as Lawrence’s superior General Allenby, had to act a long, complex scene in which they discuss Lawrence’s abuse, Lean demanded multiple takes, and eventually an irritated O’Toole shouted: “I was f----d by some Turks.” The ever-suave Hawkins, who became a good friend and drinking companion of O’Toole’s, took it in his stride, and responded: “What a pity.”

O’Toole’s relationship with Spiegel did not improve during production, and he later said of the producer: “Destruction was Sam’s game… I couldn’t bear that man.” Yet Spiegel’s masterstroke, seeing that Lean had all but gone native during production, was to announce that the film would have a Royal Command Performance on 10 December 1962, meaning that, given filming finished on 18 August, Lean would have a mere four months to cut together a four-hour film. O’Toole grudgingly admired Spiegel’s decisiveness: “I must say it was a masterstroke on Sam’s part…[he] knew we were going on too long; David and I had begun to forget we were making a film. After two years it had become a way of life.”

It had taken its toll on the actor psychologically, and physically too: he suffered a vast array of injuries, including groin strain, third degree burns, a neck sprain, cracked ankle bones, torn ligaments and a spinal dislocation. There were, on balance, easier ways to earn £12,500.

Nonetheless, when the film premiered, it was obvious that Lean had created a masterpiece, helped immeasurably by his star’s intensely committed performance. At the premiere Noel Coward approached O’Toole. The milder recollection of their encounter has Coward say: “If you were any prettier, darling, the film should have been called Florence of Arabia.” While the more risqué version had him say: “If Lawrence had looked like you, Peter, there would have been many more than 12 Turks queuing up for the b----ring session.”

Lawrence of Arabia was both a vast box office success and immensely successful at the Oscars, winning Best Film, Best Director and many other awards. It made its leading man a star, and saw to it that, until the end of his career, he gracefully winced while the Maurice Jarre theme music from Lawrence accompanied his entry on to countless awards stages and chat show sofas.

Yet Spiegel never warmed to him. “You make a star, you make a monster”, he said. And Lean shied away from the mentor role that he might have been expected to take on in O’Toole’s life and career. He called O’Toole “a real dope” to one friend, referring to the actor’s drunken appearances on chat shows – which might have cost him the Oscar – and inability to fulfil publicity commitments due to hangovers.

But O’Toole remained committed to Lean. At the director’s funeral service, he recited John Donne’s poem Death, be not proud. And when asked about their relationship, he replied: “The most important influence in my life has been David Lean. I graduated in Lean, I took my BA in Lean, working with him virtually day and night for two years.” The results speak for themselves, 60 years on.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies