A piercing screen: How Watership Down terrified an entire generation

In 1978, one of the greatest British animated films of the past 50 years was released – and arguably traumatised an entire generation. From today’s viewpoint, it’s perhaps baffling how Watership Down, based on the classic children’s novel by Richard Adams, could be considered a kids’ movie.

It plunges down a rabbit hole of distressing imagery from the start and rarely lets up. In one early scene, sensible bunny Hazel (John Hurt) attacks another rabbit after an attempt to stop him and his psychic brother Fiver (Richard Briers) from leaving their warren – and Hazel is the hero. Most haunting of all is the ghastly fate of the rabbits who ignore Fiver’s warning to flee. They are buried alive when their home is destroyed to make way for a housing development.

“That’s part of nature – nature is very tough,” explains Martin Rosen, Watership Down’s director, speaking as the film marks its 40th anniversary this weekend. “Richard [Adams] was very strong on that element. I felt it was absolutely critical. I did not make this picture for kids at all. I insisted that the one-sheet [the film poster] indicate how strong a picture it was by having Bigwig the rabbit in a snare. I reckoned a mother with a sensitive child would see that – a rabbit in a snare with blood coming out its mouth – and reckon, ‘well maybe this isn’t for Charlie – it’s a little too tough’.”

Extraordinarily, British classifiers deemed all of the above appropriate for a general audience – including the notorious sequences in which physically imposing Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox) nearly dies in a trap and the monstrous General Woundwort (Harry Andrews) casually rips open the throat of a rabbit defying his indomitable will. Comic relief, it is worth noting, is courtesy of wacky seagull Kehaar (Hollywood veteran Zero Mostel in his final role). At one point, he charmingly tells Hazel and company to “p*** off”.

There was no PG rating in the UK in 1978 – so it was either U (universal) or 15. It was felt the former was more fitting. The film’s suitability became an unlikely source of debate two years ago when Channel 5 aired it at 2.25pm on Easter Sunday. Families across Britain sat down to what they presumed would be a tale of cuddly derring-do in the woodland.

Instead, they and their children were assailed by an hour and a half of death and cruelty. After the Channel 5 switchboard and Twitter feed lit up with complaints, the head of the British Board of Film Classification intervened, saying that, released today, Watership Down would almost certainly carry a PG rating.

“The film has been a U for 38 years, but if it came in tomorrow it would not be,” said David Austin. “Standards were different then.” It’s a debate likely to be reignited when the BBC and Netflix debut their new TV adaptation of the book this December (it’s as yet unclear whether it will be as gruesome as the movie).

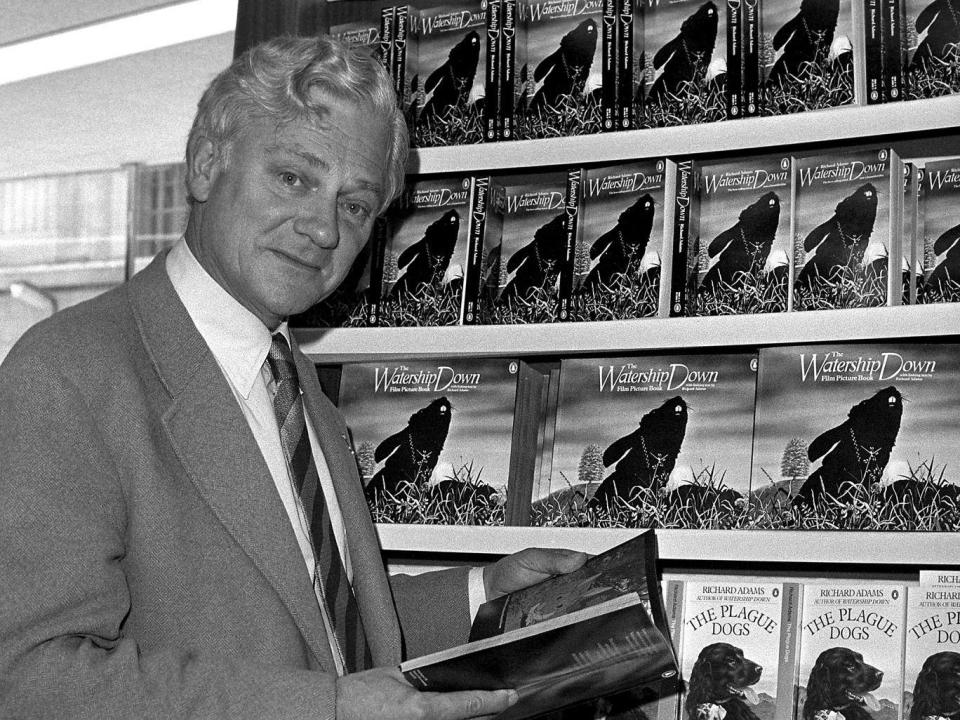

Adams, who died in 2016 aged 96, was aware his story could be considered visceral – but saw no reason why he should apologise. In an interview with The Telegraph in 2014, he said: “I never consider the readers. I was allowed to read anything I liked when I was little, and I liked all sorts of things that I shouldn’t have been reading.”

But he said the tale wasn’t allegorical – much less informed by Nazi Germany or Stalinism (he had fought in the war). Happily employed in the civil service, he came up with the bare bones of Watership Down when his children asked for a story during the school run. From this time-filler, he spun one of the great fantastical works of children’s literature.

“I had been put on the spot and I started off, ‘Once there were two rabbits called Hazel and Fiver.’ And I just took it on from there,” he remembered.

Rosen, for his part, insists he didn’t set out to distress anyone. The disturbing imagery – such as the red-eyed rabbits gasping for breath in the filled-in warrens – was in service of Adams’ story. Nobody on the production was cackling at the cruelty of it all.

“I was very surprised when everybody got crazy about it,” he recalls. “I remember taking to the censors in Sweden and saying, ‘Is there something about death you don’t want children to know about? It’s going to happen to us all.’ That sold the position and it was released to general distribution in Sweden.”

Rosen may well look back and wonder whether, to parse the lyrics of its theme song “Bright Eyes”, it really was all a dream – or a nightmare.

He’d just about persuaded the sceptical Adams that the story could translate to the screen (“he wasn’t against it but he wasn’t enthusiastic”). Then he’d cobbled together the $4.8m budget with the backing of an international conglomerate of investors, the studios having laughed in his face about a film with a male rabbit named Hazel.

The big mystery to Rosen was why he was the only one who had faith in the movie. Watership Down had sold a million copies in the UK alone in the 20 months after its publication in November 1972. The potential for an adaptation was undeniable.

Yet it appeared to Rosen that he alone believed a story so self-evidently rich in cinematic promise could make the leap to film. Having finally scraped together the money, he hired veteran animator John Hubley (creator of Mr Magoo).

But Rosen had to then fire Hubley when he discovered he was working on the side on a Doonesbury adaptation for ABC. A few weeks later, freshly sacked Hubley died during heart surgery, making reconciliation impossible. Hubley’s biggest contribution arguably had been to phone up Wombles songwriter Mike Batt several weeks previously and persuade him to compose a song about death – which would become Bright Eyes.

With Hubley gone, the only option, as the producer saw it, was for Rosen himself to step in. He’d never worked in animation before – which might explain the cinematic look to the film. He was breaking all the rules of a kid’s picture because he wasn’t aware that there were any rules.

“I was under the impression you’d be directing the actors,” he says. “You don’t – you direct the animators. The animators are the actors. You talk to them about what you want.”

Rosen isn’t sure whether Watership Down had much of an influence in the wider culture. He doesn’t see echoes of its raw honesty in, for instance, the darker Pixar films such as Up and Coco – each in their own way a meditation on mortality.

But it undoubtedly created shockwaves in the UK. Its portrayal of the British countryside as uncanny and feral resonates in everything from the League of Gentlemen to the cinema of Ben Wheatley. Those who have (perhaps subconsciously) tapped it for inspiration would have been young children in the late Seventies – the perfect age for their world view to be permanently warped by Watership Down.

On the other hand, the idea that such films have the potential to distress an entire generation has been challenged by recent research. Death on the screen can provide a healthy basis for children to discuss difficult subjects, a 2017 University of Buffalo study found.

“These films can be used as conversation starters for difficult and what are oftentimes taboo topics like death and dying,” said a study author. “These are important conversations to have with children, but waiting until the end of life is way too late.”

With a BBC/Netflix adaptation due on Christmas Day, Adams’s world of feuding rabbits is likely to have a fresh lease of relevance. It already has its modern equivalents: Coco is similarly matter-of-fact about the reality of death.

Still, this type of motion picture is rare and, when you look back on Watership Down and its legacy, the real shame is that there aren’t more films that show children the world as it is, rather than how it looks when refracted through a prism of Disney sentimentality.

“I didn’t want to shock people at all,” says Rosen. “I thought I was being faithful to the book. I showed it to my kids. My son was four, my daughter seven and a half. None of the rough scenes bothered them in the slightest. [The outcry] was a puzzle.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies