'Planet of the Apes' at 50: How the simian sci-fi classic changed Hollywood franchises forever

Franklin J. Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes turns 50 on Thursday, and its legacy remains as formidable as ever. A critical and commercial hit upon its Feb. 8, 1968, release (ultimately raking in a then impressive $32 million at the domestic box office), the 20th Century Fox adaptation of Pierre Boulle’s sci-fi novel (featuring a script co-written by Twilight Zone mastermind Rod Serling) boasts groundbreaking makeup effects, a story rife with enduring racial subtext, and a twist ending second to none. Even now, its lineage is difficult to deny, having recently inspired an acclaimed modern trilogy (Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, and War for the Planet of the Apes) that deftly straddles the line between remake, reboot, and sequel (the less said about Tim Burton’s 2001 version, the better). More than in any other respect, however, Schaffner’s series originator is most famous for giving birth to a paradigm that, today, is as common as it is profitable: the continuous movie universe.

There were, of course, innumerable big-screen sequels before Planet of the Apes begat 1970’s Beneath the Planet of the Apes. In the 1960s alone, American moviegoers were treated to three Pink Panther larks and six (!) James Bond outings, the last of which, 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, replaced headliner Sean Connery with George Lazenby. What made Planet of the Apes different from 007, or Inspector Clouseau, or Universal’s monster movies (1930s-1940s), or the comedies starring Laurel and Hardy (1920s-1940s) and Abbott and Costello (1940s-1950s), was that Apes launched a series marked by a continual narrative. Whereas most followups had long been content to feature familiar heroes in new standalone adventures divorced from their predecessors — i.e., characters didn’t make references to past movies’ plots, nor did those earlier works have any bearing on the action at hand — Planet of the Apes sired cinematic progeny that were inherently beholden to that which had come before. They did their best to tell self-contained tales (lest they totally alienate newbie viewers), but fully appreciating them required knowledge of their direct ancestors.

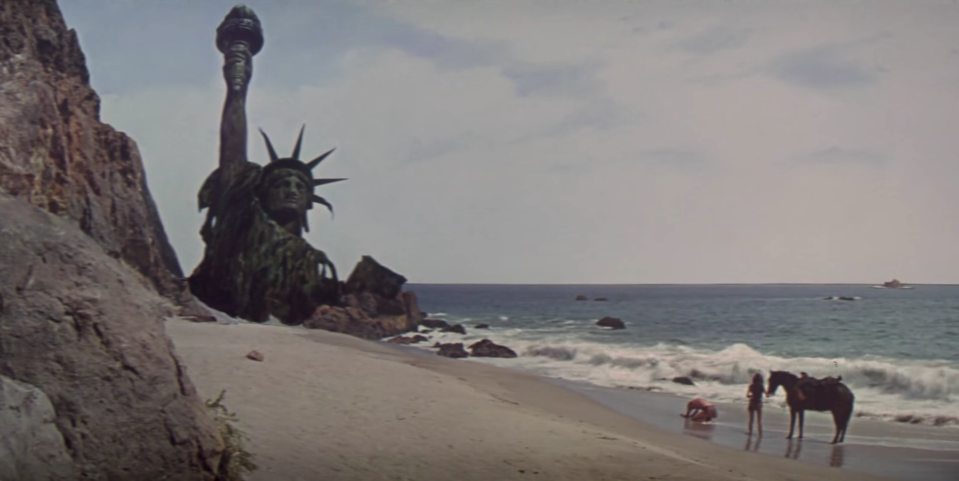

Thus Planet of the Apes aligned itself most closely with the serialized shorts of the first half of the century (think Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy), which recounted one story line over multiple installments. Not that this was the initial plan; Planet of the Apes was a dicey proposition for Fox, which only agreed to bankroll a second effort after Schaffner’s original became a bona fide hit. Nonetheless, even if the franchise didn’t commence with an overarching five-film plan, producer Arthur Jacobs quickly took a longer view of its mythology. Despite featuring arguably the most iconic closing shot in cinema history — the discovery by Charlton Heston’s astronaut of an ancient Statue of Liberty, which indicates that this ape-ruled world is future Earth — Planet of the Apes provided a jumping-off point for extensive world-building. And in fact, its immediate successor, Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), functions as something like the second half of a two-part story, culminating in its own unforgettable conclusion: the apocalyptic detonation of a nuclear device.

With nothing left after Beneath, 1971’s Escape from the Planet of the Apes had to get creative — and it did, by claiming that everyone’s favorite simian couple, Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) and Zira (Kim Hunter), had actually escaped Earth’s destruction by hopping in a spaceship and traveling back in time to our present day (circa 1971).

That twist, in turn, allowed the series to chart a (largely singular) course that carried it through 1972’s Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and 1973’s Battle for the Planet of the Apes, which ended in a way that made it feel like all five films had told one unified, circular-logic tale. Since this odyssey hadn’t been mapped out from the start, plot holes were, ahem, easy to spot at various points along its convoluted timeline. And the fact that Fox kept slashing budgets for each sequel didn’t help maintain an across-the-board level of production quality. Yet the end result was unique — a large-scale genre saga spanning five interconnected chapters.

Hollywood, as everyone now knows, took notice. The Godfather was split in two, to Oscar-winning glory. Star Wars spawned The Empire Strikes Back and, in the process, was retrofitted as Episode IV of an in-progress epic. Then came the View Askewniverse, the X-Men movies, the Harry Potter adaptations, the Lord of the Rings blockbusters, and now the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a collection of standalone comic-book affairs that were first tethered only by post-credits scenes, and are now so intertwined that they’re constantly crossing over with each other and picking up where the prior one left off — all while existing in a common fictional reality. The MCU’s unrivaled success has, in turn, led every studio to try to duplicate that template, be it Warner Bros. and DC Comics with their Justice League-centric superheroes, or Universal and its (already DOA?) Dark Universe.

Planet of the Apes gave us all of this, at least on the larger-than-life scale that has become standard Hollywood practice. Whether that heritage is, in the final tally, a net positive or negative no doubt depends on how one views today’s big-budget movie landscape. But there’s no denying that, 50 years after its premiere, it still stands as a shared-continuity classic far ahead of its time.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies