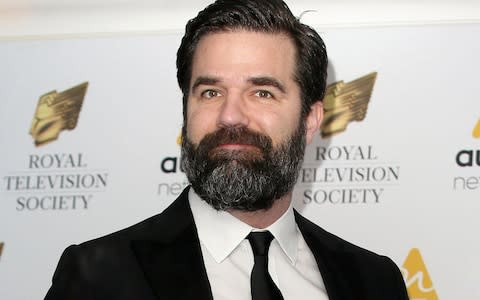

Rob Delaney on the pain of losing his two-year-old son: 'Our family’s story has a different ending than I’d hoped for'

I’m on the bus to go see my son Henry at the hospital. I have to take him in a taxi to another hospital for some specialist doctor appointments they don’t do at the hospital at which he lives. I don’t want to take him on the bus to the other hospital because I don’t want to have to jostle with other curious passengers when I have to turn on his suction machine to suck out the saliva and mucus that collects in his tracheotomy tube.

He would love to go on the bus though. He’s two. Despite the physical disabilities he has from the surgery to remove his brain tumor, he’s very sharp mentally and gets as excited about a big red double decker bus as any other little boy. I’ll take him on a bus soon and if it makes anyone uncomfortable they can suck my d***.

Metaphorically; my family needs me too much for me to get sent to prison for trying to force a stranger to suck my d*** on a bus. I go past two prisons on the way to the hospital though so maybe it could work.

I’m so f*****g tired. The front of my head feels like it’s stuffed with hot trash. My chest and throat feel constricted and I’m reminded that while my life is and will remain stressful for the foreseeable future, I could at least lose some weight to reduce my heart’s workload, so a cardiac event doesn’t take me out before I turn fifty.

My biggest fear had always been that I wind up somehow being conscious for eternity. Like that I die, wind up in heaven or hell or wherever and I remain “me” and just never shut off and have to endure being conscious and aware and nothing is wonderful enough or horrible enough to engage me for that long, i.e. eternity. That might be a factor in the heavy drinking I quit 15 years ago; the idea that I could really effectively hit my own consciousness’ kill switch as needed. Might also be why I’ve always enjoyed naps more than food or money.

I could just call to mind the image of one of my sons, or the smell of their heads, or the feel of one of their little feet in my hand and I’d be happy

That fear went away when my wife and I had kids. Or boys, specifically. My sperm only makes boys for some reason. The fear went away because I realised I could now do eternity and be okay. I could just call to mind the image of one of my sons, or the smell of their heads, or the feel of one of their little feet in my hand and I’d be happy. Give me a Polaroid of one of them to hold on to and I could do two eternities.

I may wish Henry wasn’t in the hospital and it may make me f*****g sick that my kids haven’t lived under the same roof for over a year. But I’m always, always happy to enter the hospital every morning and see him. It’s exciting every day to walk into his room and see him and see him see me. The surgery to remove his tumor left him with Bell’s palsy on the left side of his face, so it’s slack and droops. His left eye is turned inward too, due to nerve damage. But the right side of his face is incredibly expressive, and that side brightens right up when I walk into the room.

There’s no doubt about what kind of mood he’s in, ever. It’s particularly precious when he’s angry because seeing the contrast between a toddler’s naked rage in one half of his face and an utterly placid chubby chipmunk cheek and wandering eye in the other is shocking in a way that makes me and my wife and whatever combination of nurses and/or doctors are in the room laugh every time. And when he smiles, forget about it. A regular baby’s smile is wonderful enough. When a sick baby with partial facial paralysis smiles, it’s golden. Especially if it’s my baby.

A little over a year ago Henry vomited at his oldest brother’s fifth birthday party. No big deal; he was our third kid and we’d cleaned up enough gallons of puke not to be fazed. I’d been feeding him blueberries so there were maybe fifteen or twenty recognizable blueberries in there. Did I feed him too many? Had I done something wrong? He was eleven months old at the time. Was I being a lazy parent and had I just let him keep eating them because it kept him quiet?

Those questions ran through my mind but if he’d puked them all up it didn’t really matter. He was our third; I’m pretty sure I let him eat chorizo before he was nine months old. It’s not like your first kid where you bug out over every little thing that goes into their mouth. Want some chorizo? Go nuts little man. Chorizo’s good, why wouldn’t you want some?

I’m glad I gave it to him too because he hasn’t eaten anything via his mouth for a year now. Now he’s fed through a tube in his stomach. Some s*** called Pediasure Peptide. One nurse I know hates it because it smells the same when kids vomit it up as it does fresh out of the bottle. And kids on chemo vomit a lot. So she feels like she’s feeding kids vomit.

After Henry vomited that first time at his brother’s birthday party, we cleaned it up and kept on partying. The next day he vomited a couple more times so my wife called a nurse who said to bring him into Accidents and Emergency. She wanted to make sure he didn’t get dehydrated. For some reason at the A and E they got the idea he might have a urinary tract infection.

Since he couldn’t really keep fluids down very well, they asked me to feed him five mils of some electrolyte juice through a syringe every 5 minutes and hold a little cup next to his penis to catch any urine he might produce so they could see if it was in fact a UTI. That was actually fun, holding a cup under his adorable little eleven-month-old penis and nursing him little squirts of juice every five minutes.

It was sort of meditative and we just stared at each other the whole time. I couldn’t look at my phone or watch Finding Nemo on the A and E TV, lest I miss a drop of that precious pee he was resisting giving me. He finally made a little pee and I gave it to them and we left with some antibiotics, with the understanding they’d call us and tell us if a UTI was the culprit.

He continued to vomit, but it tapered off a bit and it seemed like he was at least taking in more calories then he’d bring back up onto the floor from time to time. Still though we were concerned so we brought him to our local general practitioner. A doctor examined him and while we were there, Henry vomited all over the floor. I was glad he vomited in front of the doctor. I wanted to point at the vomit on the floor and say, “See asshole? That’s vomit alright. Now what are you going to do about it?” What he did was give us an appointment to see a gastroenterologist. That made sense to me, since up to that point in my life, vomit-related issues generally centered in the stomach.

The vomiting plateaued a bit and we decided to keep the plans we’d had to visit the United States for the Easter holiday. Henry turned one. Then the vomiting intensified. While visiting my mom in Massachusetts we took Henry to an American hospital. For a five-hundred-dollar deposit, they did an ultrasound on his kidneys to see if they were infected. They didn’t seem to be. They put him on different antibiotics.

We returned to London and started to get scared. Henry was losing weight. Every time he vomited I would freak out. I would feed him so gently, so slowly, and assume I’d done something wrong when he vomited. Why, if I’d been able to feed Henry’s ravenous, feral older brothers, couldn’t I feed him? I would imagine collecting the vomit somehow and pouring it back into him with a funnel.

My baby was getting smaller, and that is a f****d up thing to see. The total amount he weighed was less than the amount of weight I should lose. Henry didn’t have any weight to lose! His vomit became the most precious substance in the world to me and I would often start crying whenever he threw up. I would try not to cry in front of his older brothers and fail and they’d ask why, and I would say it was because I was scared.

The gastroenterologist prescribed a drug that’s supposed to make you not puke. He puked anyway. By this point we knew we were going to get some kind of bad news, we just prayed it would be celiac disease or a twist in his gut that could be surgically fixed or something.

Then my friend Brian, whose kids are older than ours, recommended we go see their family pediatrician. He said he’d helped them solve a medical mystery with their son a few years ago and what the hell, it was worth a shot.

Like every other appointment, I took Henry to Dr Anson myself. My wife is a magnificent mom and is insane about our children and would have happily taken Henry but for whatever reason I’d taken him to the first appointment so we just kind of stuck with that and he became my little project. My wife stayed with our older boys who were five and three and were, frankly, usually the more difficult job posting.

Dr Anson called Henry and I into his office. He was pleasant and probably in his late sixties. He checked out Henry and was as alarmed as anyone to see the loose skin on his inner thighs.

He asked some routine questions but then he asked one that stuck out from the others: “Is his vomiting effortless?”

“Effortless.”

“Yes, does he retch, or seem distressed when he vomits? Or does it just come up and out?”

“Hmm, huh, um, it is effortless, yeah. He’s not troubled at all.”

“Okay, I think we should schedule an MRI. Of his head.”

“Okay, why?”

“Just to make sure there’s nothing in there that shouldn’t be. Pressing on his emetic center, making him vomit.”

“What, like a tumor?”

He paused.

“I’m glad you said it.”

Henry just turned two. We didn’t dare assume he’d have a second birthday with the prognosis he received after they took out the tumor and confirmed what kind it was. It was a real c*** of a tumor. An ependymoma they call it. Ependymomas kill most babies who get them. If I’d had one when I was Henry’s age in the 1970s I would’ve almost certainly died.

You probably would have to if you’re old enough to be f****d up enough to want to read a story about a baby who got a brain tumor. They still kill people today but if they can remove the entire thing surgically your chances improve somewhat. Henry’s was on his posterior fossa, wrapped snugly around several important cranial nerves. To get them out, his surgeon, Dr. Mallick had to damage these cranial nerves. Thus, the Bell’s palsy and the lazy left eye.

The cranial nerve that serves the left ear was severed, so he’s deaf in that ear now. All those things are awful, but they’re really nothing compared to the tracheotomy. The nerves that handle swallowing and gagging were damaged, so Henry can’t prevent saliva from getting into his lungs. You and I swallow about a liter and a half of saliva every day without knowing it. Lose your swallow and you’d get pneumonia pretty quickly, and pneumonia kills people as dead as cancer does.

Henry’s tracheotomy tube prevents him from speaking, so I haven’t heard him make a peep for over a year. My wife recently walked in on me crying and listening to recordings of him babbling, from before his diagnosis and surgery. I’d recorded his brothers doing Alan Partridge impressions and Henry was in the background, probably playing with the dishwasher, and just talking to himself, in fluent baby. F*****g music, oh my God I want to hear him again. Now he has a foam-cuffed tracheotomy tube in his beautiful throat, rendering him mute.

My wife recently walked in on me crying and listening to recordings of him babbling, from before his diagnosis and surgery

The other day I had to use no small amount of my adult strength to hold him down on a hospital bed while a nurse and a doctor took out his tracheotomy tube, which had broken. It bled like hell because of aggravated scar tissue around the stoma, so I suctioned the blood out of the hole in his throat, while they got ready to put in the replacement tube. It was awful, and Henry was terrified, begging me to pick him up and take him away. But I didn’t. I held him down. The hole in his throat is about the same circumference as a bullet hole.

I’ve gotten to know his tracheotomy nurse rather well. She was a captain in the British Territorial Army and served in Iraq and Afghanistan. She also helped turn Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children into a triage unit for adults on the day of the bombings in London on July 7th, 2005, which killed 52 people. So even though I f****** hate what she’s taught me to do to my beautiful baby boy’s neck, I’m grateful to have her around to talk me back to sanity afterward.

I’m aware this ends somewhat abruptly. The above was part of a book proposal I put together before Henry’s tumor came back and we learned that he would die. I stopped writing when we saw the new, bad MRI. My wife and his brothers and I just wanted to be with him around the clock and make sure his final months were happy. And they were.

The reason I’m putting this out there now is that the intended audience for this book was to be my fellow parents of very sick children. They were always so tired and sad, like ghosts, walking the halls of the hospitals, and I wanted them to know someone understood and cared. I’d still like them to know that, so here these few pages are, for them. Or for you.

But I can’t write that book anymore because our family’s story has a different ending than I’d hoped for. Maybe I’ll write a different book in the future, but now my responsibility is to my family and myself as we grieve our beautiful Henry.

Note: I wrote all of this except the last paragraph in April or May of 2017. I changed names as well, except for Henry’s.

The fee for this article will be donated to the Rainbow Trust: https://rainbowtrust. org.uk/latest-news/in-henrys- name and Noah’s Ark Hospice: https://www. noahsarkhospice.org.uk/in- henrys-name/

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies