Screen play: our writers pick their favourite sports movies

Bull Durham

The greatness of any Ron Shelton sports movie has as much to do with that isn’t in them as what is. Shelton’s Bull Durham, as with follow-ups like White Men Can’t Jump and Tin Cup, has no Big Game ending or inspirational schmaltz, and features a flawed, never-was athlete whose triumphs are known to few outside his inner circle. In a breezily assured performance, Kevin Costner plays a journeyman catcher who’s spent almost no time outside the minor leagues, where his job is teach the finer points of the game to cocky young flamethrowers like “Nuke” Laloosh (Tim Robbins) before they graduate to “The Big Show”. Coaching arrogant dopes to live out your dream is humbling work, but Shelton savors the smaller, unseen victories for his hero, like his relationship with a minor-league “groupie” (Susan Sarandon) who represents a tantalizing off-season promotion. As a former minor-leaguer himself, Shelton parlays his understanding of baseball rituals, superstitions and gimmicks into a hilarious, impeccably detailed romantic comedy. Scott Tobias

Miracle

Growing up in a hockey family in the US, the 1980 Olympic game between the USA and USSR was canon. And Miracle, the 2004 film directed by Gavin O’Connor and starring Kurt Russell as legendary coach Herb Brooks, was an important pillar of worship. It is the perfect American sports fantasy: a scrappy, strapping bunch of college kids with trivial yet deeply held regional differences come together with their laser-focused coach to defeat the Soviet Goliath (and, by extension, Communism). I have seen Miracle so many times – in the car on the way to and from tournaments, in the basement with teammates, quoted in the locker room – that its recreations of the team’s development into a single unit of belief (and Kurt Russell’s plaid suits) are part of the bedrock of my movie memory. In some ways, I’ve outgrown it – overt patriotism doesn’t hit the same now. But on the most recent rewatch it still delivered on the hype I remembered: the momentum of an underdog story, the electric cacophony of the rink, the thrill of believing. Adrian Horton

Rocky

What’s left to say about the one that started it all? The quasi-apocryphal origins of Sylvester Stallone’s career-defining opus are firmly embedded in the Hollywood mythos: written in three and half days by an out-of-work B-movie actor who defiantly held out for the lead role and shot in four weeks on a shoestring budget against the same industrial Philadelphia waste land that inspired David Lynch’s Eraserhead, it became 1976’s highest grossing film and piled up 10 Oscar nominations (winning the Big One), drawing audiences that cheered Stallone’s everyman palooka from their cinema seats like he was a real-life fighter. Yet maybe due to the money-spinning franchise that followed – the eight largely generic sequels, the Broadway musical, the mass-market novelizations and video games – the original is somehow under-appreciated for what made it special: a tender, naturalistic character piece with a note-perfect script bound to universal themes of ambition, redemption and the drive for victory on one’s own terms. Bryan Armen Graham

Moneyball

As someone who doesn’t count sports as a major part of my life, the best sports movies find a way to suddenly make me briefly, terribly invested in something I may never be invested in again. My continued enjoyment of the Creed series has not caused a desire to endure the overpriced horrors of real boxing and since 2011, after gliding out of a press screening of Moneyball, I’ve paid zero attention to baseball ever since (aside from a rewatch or two of Tony Scott’s strange and affecting 1996 thriller The Fan). But in those two hours, I was utterly enraptured by the detailed inner workings of the Oakland A’s and how studying statistics and using calculations helped them outfox richer competitors. It was partly because Brad Pitt was at his effortless movie star best and partly because Aaron Sorkin’s elegant dialogue was avoiding his showy, overwritten worst, but mostly because the world being created was such a rich and textured joy to be a part of – explained just enough to a layman like me and exciting not because of the grand theatrics of what was happening on the field but the greater wealth of what was taking place off. Benjamin Lee

The Cutting Edge

The film that immortalized the phrase “toe pick!” and the first written by Andor showrunner and Bourne films screenwriter Tony Gilroy, this 1992 gem features a career-best Moira Kelly as a rich bitch figure skater who has driven away every prospective pairs partner with her haughtiness. She meets her match in DB Sweeney, playing a blue-collar former Olympic hockey player sidelined by injury and itching to get back on the ice. It’s detestation at first sight, and the pair’s crackling chemistry propels the film beyond the expected blurry action shots and physically impossible finale move (not to mention lines like: “There are two things I do really well, sweetheart, and skating’s the other one.”). Think Taming of the Shrew on ice, bolstered by an excellent early-90s soundtrack and a canny tapping into the era’s craze for all things figure skating, near the height of the Tonya Harding–Nancy Kerrigan rivalry. Lisa Wong Macabasco

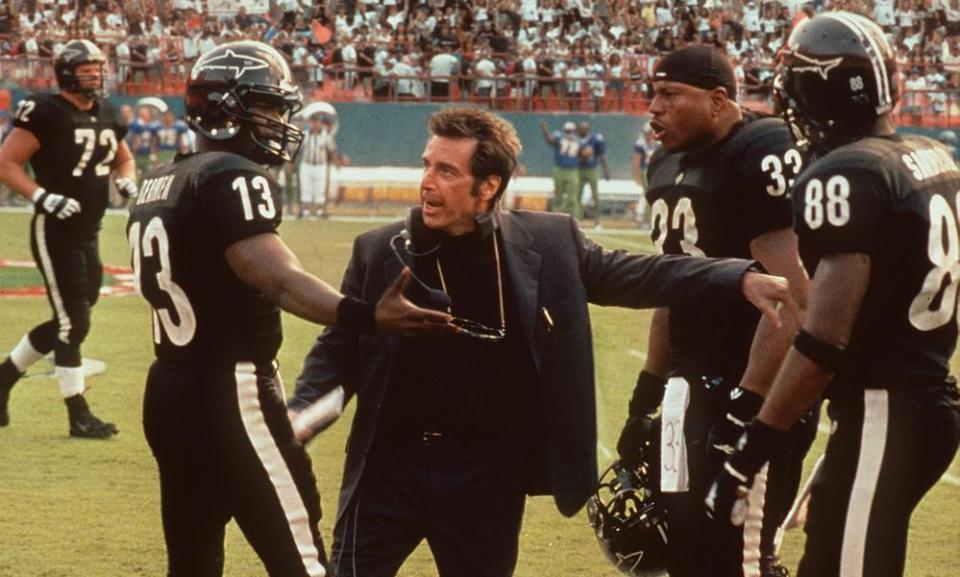

Any Given Sunday

There are two types of sports feature films: the saccharine sweet tale of the plucky player/coach/team who overcomes the odds, or Any Given Sunday – which pulls back the curtain on professional football. Vulgar, graphic and boiling over with tension, an NFL Films production this is not. Sunday’s gonzo tone is set by director Oliver Stone, a master of the form who deftly embroiders a complex narrative about the ripple effects of a quarterback controversy on a franchise and coach in faded glory. Stone adds to the realism by sprinkling Jim Brown, Lawrence Taylor and other gridiron legends into a stacked cast led by Al Pacino and Jamie Foxx. Among other things, the film was early in flagging the impact of repetitive brain injuries and team efforts to minimize the damage. And yet: the bit that always gets me is Pacino’s Coach D’Amato at full throat. I’d run through a wall for him any day. Andrew Lawrence

Hoop Dreams

If the late critic Roger Ebert had the good sense to call a three-hour videotape documentary about two high school basketball players the best film of the 1990s – placing a lo-fi underdog that happened to be a Dickensian masterpiece over Goodfellas and Pulp Fiction – then Hoop Dreams, which follows two poor Black boys who happen to be better at basketball than most, certainly deserves a place on this list. Director Steve James’s intimate portrait of Arthur Agee and William Gates, both harboring dreams of using their talent to escape poverty, is less about the adrenaline rush of a Friday night victory than it is about shining a light on an entire system that depends on exploitation for its excitement. A young Spike Lee makes a cameo in the film, and comes in with hard truths to the young players: “The only reason you are here is because you can make their schools win and they can make a lot of money,” he says. “This whole thing is about money.” Coming on thirty years after its release, Hoop Dreams still cuts through the churn. It’s a rare work that is a lesson in how systemic injustice can bleed a community dry, and what art can be. Lauren Mechling

Ali

The training montage that you see in almost every sports movie before the big game/fight/match comes right at the beginning in Ali, and it’s unlike any other we’ve seen before. The young boxer played by a dedicated Will Smith works a speed bag and goes for a run while suspicious police cars prowl nearby. Those moments are woven into a soulful and expansive tapestry: memories of seeing Emmett Till’s disfigured body in the newspaper, Malcolm X preaching, Sam Cooke crooning. It’s a prologue that makes immediately clear that the heavy lifting for Muhammad Ali had nothing to do with barbells and body mass. He was training his whole life to shoulder the weight of history and being a symbol. The opening, which stays true to Ali’s “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” mantra in its storytelling, sets the tone for rest of Michael Mann’s beautiful testament to the conflicted civil rights era icon. The power in his film is how it fearlessly embraces the messiness in activism, the tension between Ali’s selfishness and self-awareness and the ultimate sting when his Rumble In The Jungle victory in Zaire benefits CIA-backed kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko. The movie admits that even Ali’s wins can at times feel like a loss. Radheyan Simonpillai

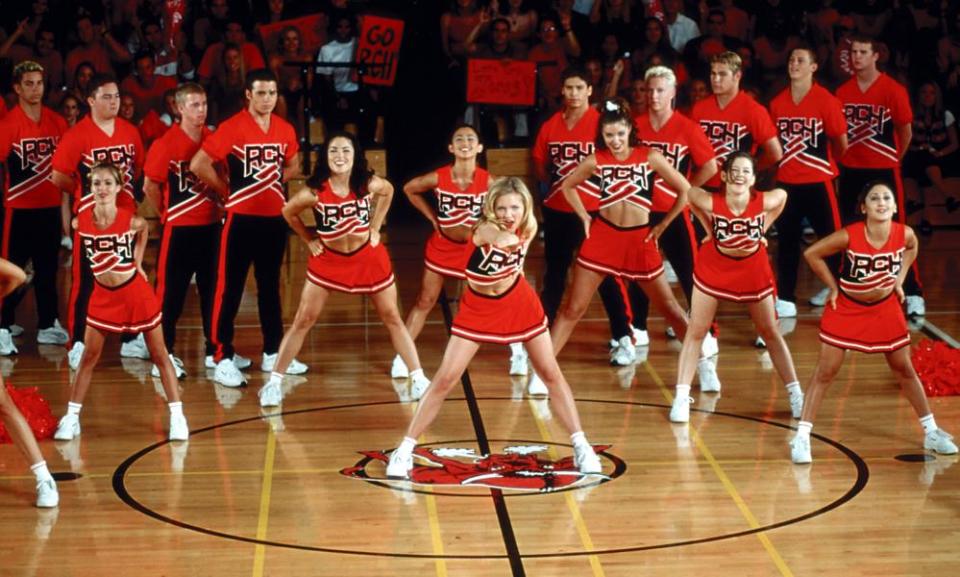

Bring It On

Arriving amid a spate of unapologetically female-forward comedies like Legally Blonde, Clueless, and Mean Girls, Bring It On is proudly and magnificently itself. High-energy and frenetic, the movie never really slows down as it chronicles the ups and downs of the ultra-privileged Rancho Carne high school cheerleading squad and their run-ins with the East Compton Clovers, omegas to Rancho Carne’s alphas. The movie features Kirsten Dunst showing off her comedy chops and closing out a career-making run of hits that began with 1994’s Interview with a Vampire and left her a dominant A-lister. It also also low-key delivers an impressive amount of intersectional feminism for a supposedly vapid millennial flick, anticipating much of the reckoning that would sweep over more prestigious Hollywood fare in the next two decades. Never really getting its due, it spawned a brand that currently includes 6 legacy sequels, a stage musical, and a loving homage in the video to Arianna Grande’s hit single Thank U Next. What more do you need to say about this movie than that even the great Roger Ebert recanted his original negative take? Veronica Esposito

Raging Bull

There are sports movies and sports movies. Some are about the sport itself, designed to thrill or disgust you with whichever beautiful game takes your fancy: The Natural, maybe, or The Damned United, or Hoop Dreams. Others use the sport as backdrop, a trigger for an entirely different film about something else completely: Field of Dreams, say, or Escape to Victory, or Foxcatcher. Few films are brilliant on both, like Raging Bull. An amazingly photographed homage to a very specific, very brutal period in American boxing in the 1940s and 50s, equally saturated by organised crime and racism, Raging Bull is also an unblinking study of what in those days (the 1950s, or the 1980s) wasn’t called “toxic masculinity”; Robert de Niro, in what remains arguably his greatest role, was brilliantly plausible as an Italian-American slugger of the old school, and a vicious, unreconstructed domestic abuser. As a sports movie, it’s out on its own. Andrew Pulver

Diamantino

Everyone knows that all sports movies are really about something else, it’s just that those other things are usually pretty boring: believing in yourself, overcoming hardship, learning to set aside ego and be part of a team. But in the misadventures of holy-fool-as-himbo Diamantino Matamouros (Carloto Cotta), a world-renowned Portuguese footballer with more than a passing resemblance to Cristiano Ronaldo, writer-directors Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt concocted a demented political thriller in which the “beautiful game” matters less than the fluidity of gender, the sinister machinations of the state, and Western attitudes toward refugees. A screw-loose satire involving money-laundering, lesbian secret agents, a government cloning conspiracy, and hallucinations of giant fluffy puppies swirls around the pure-hearted moron Diamantino, the European obsession with World Cup victory reduced to a grand surrealist joke in a finale that rejects victory as its ultimate aspiration. Its final conclusion that there’s more to life than kicking a ball gives the athleticism-averse among us something worth cheering for. Charles Bramesco

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies