‘It’s Shakespeare – as important as any modern piece of work’: Derek Jarman’s Blue comes to the stage

Neil Bartlett vividly remembers his first glimpse of Derek Jarman’s work: covertly watching the film Sebastiane (Latin dialogue, glistening flesh). “How I managed to do that without my mum and dad finding out,” he marvels. “I was captivated. That’s when Derek became public property – Mary Whitehouse and her cohorts were frothing at the mouth. And my young man’s cultural gaydar went: ‘Oh, what’s this?’”

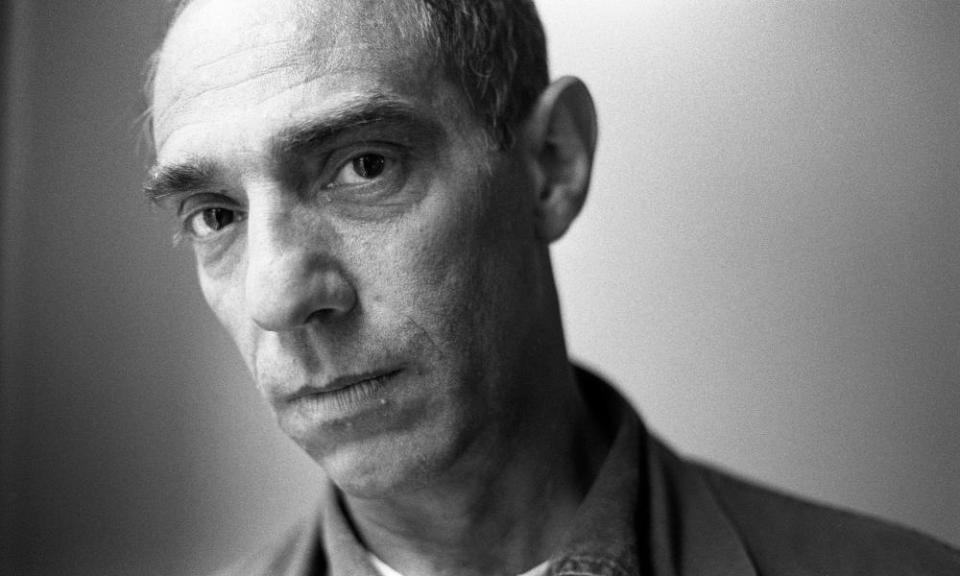

As a painter, writer and film-maker, Jarman was a unique figure in British culture: an icon of the Thatcher years who defied all they stood for. He never hid his sexuality, and nor did he hide his Aids diagnosis, despite the snarling hatred shown towards people living with the disease. His final film, Blue, premiered in June 1993, less than a year before his death. Over a static, unchanging shot of Yves Klein blue, Jarman and some of his long-serving collaborators narrate a text that is scoured by illness, fired by fury and radiated by lyricism. The film plays like a sound collage, a meditation on love, loss and the colour blue as the director comes to terms with his illness and loss of sight (he can only see in shades of blue) yet retains his ardent intensity. “Our lives will run,” Jarman insists, “like sparks through the stubble.”

New generations of queer artists continue to encounter Jarman, often indirectly. For the actor Russell Tovey it was his music video for It’s a Sin: “It carries such weight and felt like a manifesto for the climate.” He later sang the number in Alan Bennett’s play The History Boys (“the Pet Shop Boys were there on the opening night”). Writer and performer Travis Alabanza discovered Jarman “via loads of other artists referencing him – his name kept popping up”. In 2017, Alabanza performed in a stage adaptation of Jubilee alongside Toyah Willcox, from Jarman’s original film. “That was an education. Because I’m a bit of a research nerd, it made me go through all of Derek’s archives.”

The research continues on Blue Now, an ambitious project marking Blue’s 30th anniversary. Bartlett directs four performances, starting at the Brighton festival. Tovey and Alabanza will perform Jarman’s text with poets Jay Bernard and Joelle Taylor, to a live score by Simon Fisher Turner, Blue’s original composer and a direct link to Jarman’s arch and angry oeuvre.

Fisher Turner had no idea who he was meeting in 1977. “Somebody offered me a job working for a painter bloke I’d never heard of,” he says cheerily. “Suddenly, I was driving Derek around and helping make salad dressing.” His vinaigrette clearly made an impression: having begun by doing odd jobs around the studio, he went on to compose scores for Jarman’s films.

Tovey, an evangelist for modern art, owns one of Jarman’s Dungeness landscapes: “these thick impasto paintings, full of energy, that he made when he was starting to lose his sight.” He saw a screening of Blue with live sound in Paris, and was convinced that it should be brought to new audiences in the UK, with a professional director and live actors. He and Bartlett had each independently contacted Jarman’s producer, James Mackay, and combined forces.

I don’t know why it’s not taught to sixth-formers. It’s Shakespeare, it’s as important as any modern piece of work

Simon Fisher Turner

Another yes came from Fisher Turner, whom Tovey describes as “the absolute connection with Derek. I was going: ‘What do you think about the music?’ And he just said: ‘I could probably do it on the night. I’ll just improv and we’ll work things out.’ My jaw was on the floor. You fucking kidding me? You’re like holding hands with Derek and holding hands with us.”

Fisher Turner is endearingly modest about his contribution to Blue – “he could have gone to far better composers” – but the director clearly trusted him. “He came to the studio occasionally and brought cakes, but he just let us get on with it.” Jarman’s voice was too frail to narrate the entire text, which he shared with actors Tilda Swinton, Nigel Terry and John Quentin. Jarman’s reflections are cradled by a tapestry of sound: Fisher Turner’s music and a soundscape he created with Marvin Black, with snatches of music by Brian Eno and Satie, ticking clocks and other scraps of found audio. For the new performances, Fisher Turner says, “I’m using very little from the film. I have a totally different approach now. Some of it is music, some of it is sound – a bed for the actors to jump up and down on.”

“When we originally finished Blue, I thought: ‘I never need or want to do another film, because it’s the ultimate film,’” Fisher Turner adds. “I don’t know why it’s not taught to sixth-formers. It’s Shakespeare, it’s as important as any modern piece of work.” Although we might think of Jarman as primarily a visual artist, Blue showcases a writer of lyrical intensity. “Blue is arguably his most delicate work,” Alabanza says. “It’s how observational Jarman is – even as he lost his sight, he was actually looking at so much.”

What audiences will gaze at is the unchanging, richly blue screen. “It’s a definite happening,” Tovey says, “it’s going to be a completely different experience at each venue.” The atmosphere will change between the plush Theatre Royal in Brighton and the snug cinema at Home in Manchester, from London’s Tate Modern to the Turner Contemporary in Margate, where the beating sea will be visible from the gallery. Tovey tries to prepare people for an experience. “It’s going to be a meditation – you will ebb and flow, you’ll be in your own thoughts and then you’ll be back in the room. It’s gonna be trippy. There’s no other art pieces like this.”

At Bartlett’s London office, images above the desk include those of David Bowie and Jean Genet. Bartlett’s output is questingly various – recent works include a novel, Address Book, and an adaptation of Orlando starring Emma Corrin. He met Jarman when, as mistress of ceremonies (“I used to do the whole thing in drag”) at the National Review of Live Art festival in Glasgow in 1989, he invited the artist to make an installation. “I phoned Derek up. He said: ‘Oh darling, come round for tea.’ That was straight away a lesson in his generosity. He had the most perfect manners of anyone I’d ever met.”

Created “at the height of the furore over Clause 28 and the firestorm of populist homophobia”, Jarman’s installation was a room wallpapered with tabloid headlines and lined with tarred and feathered mattresses. At its centre was “a bed in a cage of barbed wire, with two people asleep or lazing. People reacted very strongly. Someone tried to call the police because they were incensed that two disease-carrying monsters should be fornicating in a building where there were children. Derek was completely unfazed.”

Cheekily canonised in 1991 by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence – a group of radical male nuns – Jarman is crucial to the knit of queer identity. “One of the best things about being queer is that as a community we acknowledge our elders,” Bartlett says. “If you want to know how to organise a demo, work a look, break up with dignity or fuck better, ask someone over 60.” Bartlett’s own mentors include Jarman and “a queen called Blanche in the Isle of Dogs who explained how to use your shoes as a weapon if you got cornered on the way home on a Saturday night. Whatever you need, our community wisdom is there for you.”

Related: From Derek Jarman to Captain Scott: the soundtracks of Simon Fisher Turner

“Blue is part of that,” he continues. “This is a thank you to Derek and his generation. He came out as HIV positive, repeatedly stood in the eye of the storm of homophobia of every kind. He took that on.” Bartlett remembers his own gay male friends frequently being queer-bashed in 1993. Now, he says, “all of my trans friends have been assaulted this year. How is it possible that the world could have changed so much in 30 years? And yet, not.”

Alabanza, 27, wasn’t even born when Blue was made. How do they view that febrile era? “My sense of that time might be romanticised in terms of its horror and its resistance,” they consider. “So many people were lost and so many people had to grieve. But it seems like from that came a true sense of resistance and community. There were great examples of people stepping up and truly acting up. We’re in a different time, but I wish there were more big, bold ‘fuck yous’ to these things.”

The urgency of this project also fires Tovey. “It feels more important than ever. The [anti-LGBTQ+] rhetoric that’s starting to bleed from the States has to be curtailed. Ancestors like Derek worked their tits off so that I’m able to say I’m queer. What they were fighting and making art about in the 1980s is still vital and necessary.”

Jarman’s narration squares up to his mortality, to his passing. Yet his influence remains – the collaborators on Blue Now hope survivors of that era will share the space with young people formed by our own fearful moment. “We want the different generations to be able to sit next to each other,” says Bartlett, “and get some peace and courage. That’s my abiding memory of Derek: grace and courage. We need those things.”

Blue Now premieres at Brighton festival, 7 May; then Turner Contemporary, Margate, 13 May; Home, Manchester, 21 May; Tate Modern, London, 27 May. Visit fueltheatre.com for more information.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies