Sidney Poitier obituary

Sidney Poitier, who has died aged 94, was the first black actor to win an Oscar in a leading role, in 1964, for his performance in Lilies of the Field. This simple story about a handyman helping German nuns build a chapel in Arizona was enhanced by its star’s humour and vitality. It led to a string of successes – To Sir, With Love, In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (all 1967) – which made Poitier a box-office star and consolidated his growing fame and wealth. But Poitier’s greatest achievement – alongside his friend and occasional rival Harry Belafonte – was to help alter the racial perceptions that dominated not just Hollywood, but also society in general.

His success came against seemingly insurmountable odds. He was born two months prematurely into extreme poverty in Miami, where his Bahamian parents, Evelyn (nee Outten) and Reginald Poitier, had gone to sell their tomato crop. The family remained in the US for three months before returning to Cat Island, where Sidney spent his early childhood. They moved to Nassau in a vain search for a better life.

Sidney left school aged 13 to help support his family. A couple of years later, his parents sent him to New York to stay with an older brother. After a series of menial jobs, in desperation at the cold weather he joined the army – giving his age as 18. Having worked unhappily in a physiotherapy unit, he engineered a discharge, faking a psychiatric disorder. In an attempt to escape washing dishes for a living, he attended an audition at the American Negro Theater in Harlem where – virtually unable to read – he was firmly rejected largely because of a strong Bahamian accent.

According to his autobiography This Life (1980), the turning point in Poitier’s mostly unhappy early years came with this rejection. For months afterwards he worked in restaurants and, through conversation and the radio, changed his speech so dramatically that on a second audition the group accepted him. He agreed to work as a cleaner in the theatre while doing his training.

The tall, athletic and dazzlingly handsome Poitier was cast in an all-black production of Lysistrata in 1946, which was followed by another play, Anna Lucasta, and a role in a military documentary, From Whence Cometh My Help (1949), which introduced him to the screen. His Hollywood debut was No Way Out (1950); adding years to his age, he landed the role of a doctor who is racially harassed by a hoodlum.

Despite good reviews, Poitier was hardly inundated with offers, since Hollywood was only just creating worthwhile supporting roles for black actors. He moved abroad for his next part, in Zoltán Korda’s rather ponderous version of Alan Paton’s novel Cry, the Beloved Country (1951), in which he played the Rev Msimangu in support of the veteran black actor and activist Canada Lee. The film was partially shot in South Africa, where Poitier was introduced to the horrors of apartheid, when he and Lee were housed outside town and segregated in all respects.

A few minor roles followed, but Poitier mainly supported his wife, Juanita (nee Hardy), whom he had married in 1950, and children, by running a restaurant in New York. A turning point came when he was given the role of a student (cast 10 years below his true age) in Richard Brooks’ explosive Blackboard Jungle (1955). As a mixed-up kid, in a mixed-race school, he was at last in a hit movie – made famous by Bill Haley’s soundtrack, which featured Rock Around the Clock.

He worked on the engaging Goodbye, My Lady (1956), directed by William Wellman and starring the child actor Brandon De Wilde, then Brooks cast him in Something of Value (1957), set in Kenya. But the parts were few and Poitier believed this stemmed from a political blacklist as well as racial discrimination. Another break came with A Man Is Ten Feet Tall (1957), an adaptation of a TV drama in which he had played the same role. His character, a dockworker, was something of a trademark Poitier part: good-hearted, tolerant (to a point) and a balance to the white lead (in this case, John Cassavetes).

As Hollywood, rather than New York, belatedly tackled racial themes, Poitier gradually emerged as a star. After being noble in Band of Angels, and married to Eartha Kitt in The Mark of the Hawk (both 1957), which was funded by a religious group, he was offered a part in The Defiant Ones (1958). At the insistence of his co-star, Tony Curtis, Poitier shared top billing above the title – a breakthrough for the period. He and Curtis gained Oscar nominations for their roles as antipathetic convicts chained together and on the run, and Poitier received best actor awards at the Berlin film festival and from Bafta.

A setback came with Porgy and Bess (1959), in which – contractually forced into playing Porgy – he was swamped by MGM’s lavish studio version of Catfish Row and Otto Preminger’s lumpen direction. In contrast, A Raisin in the Sun (1961) was a successful film of the groundbreaking play with which he had triumphantly returned to Broadway in 1959. Now in his 30s, Poitier achieved what other black actors only dreamed of – steady work in leading roles. The low-budget Lilies of the Field (1963) brought him not only an Oscar but also another award at the Berlin film festival. He became busier – to the detriment of his marriage, which ended in 1965 – with films including, that year, The Bedford Incident, in which he was cast as a journalist, a role that, significantly, did not depend upon his race.

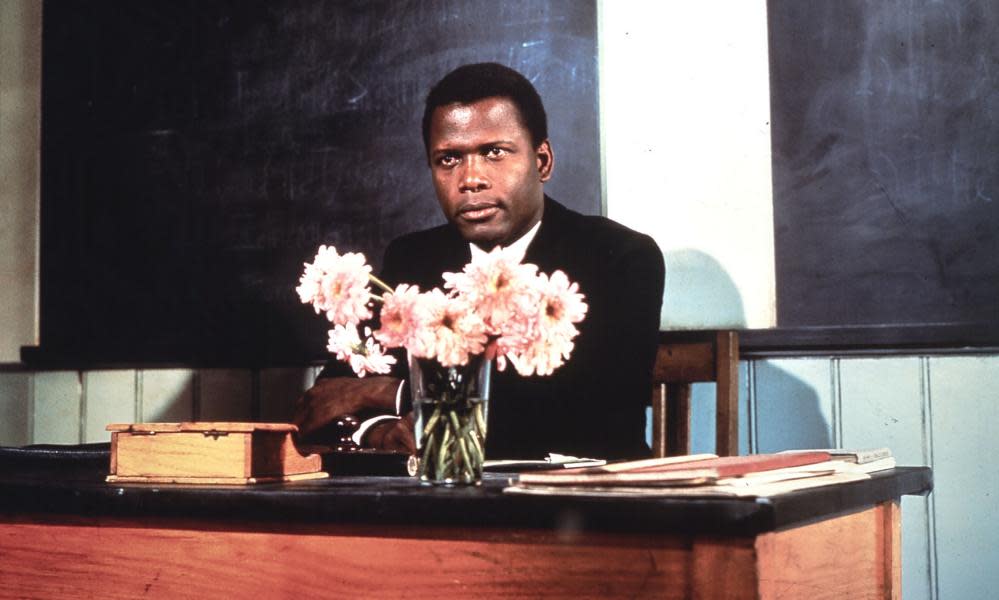

After a western, Duel at Diablo (1966), he played a teacher in the British-made To Sir, With Love, based on ER Braithwaite’s autobiographical bestseller. The movie proved a huge, unexpected, hit and Poitier, having negotiated a share of the profits to keep the budget low, became increasingly wealthy.

That rather naive view of British school life was followed by two major successes. In the Heat of the Night offered him the role of Virgil Tibbs, the Philadelphia cop who falls foul of bigotry in a Mississippi town, where the racist southern sheriff (Rod Steiger) is at odds with the immaculate cool of the black detective. He and Steiger interacted superbly under the director, Norman Jewison. It was arguably Poitier’s best performance, but it was Steiger who got the Oscar nomination (and won).

Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner completed a box-office hat-trick and further challenged race barriers. Poitier played a handsome doctor brought home by the daughter of a wealthy couple; his presence tests the parents’ liberalism, especially when the youngsters announce they are getting married. The movie is now routinely dismissed by critics as contrived and over-earnest. At the time, few considered it soft and Poitier soon found that it held the ring of truth when, after a long relationship with the black actor Diahann Carroll, he married the white actor Joanna Shimkus, provoking hostility from some quarters.

Poitier co-wrote and starred in a romantic comedy, For Love of Ivy (1968), and followed it more controversially with The Lost Man (1969), co-starring Shimkus. A revamp of the classic Odd Man Out, it cast him as a black radical on the run – rather than the IRA fugitive of the 1947 original.

Twice he revived his most famous role, in They Call Me Mister Tibbs! (1970) and The Organisation (1971). Sandwiched between these mediocre works was Brother John (1971), in which Poitier was cast as an angel descending on an Alabama town to see whether racism had lessened since his mortal time there. One can see why he was tempted by gutsier roles.

To escape the rut he turned to direction, taking over Buck and the Preacher (1972), starring as a freed slave with his pal Belafonte (stealing the movie) as a conman priest. The film humorously upended many cliches. Several of the films he directed were as the result of a newly formed company, First Artists, with Poitier, Barbra Streisand, Steve McQueen and Paul Newman each undertaking to make several films within a specified time. Only Newman and Poitier maintained their quota.

In fact, Poitier was to direct eight more films, starting with the sentimental A Warm December (1973) and ending with the lamentable Ghost Dad (1990). Few were as enjoyable as his debut, although some – notably Uptown Saturday Night (1974), A Piece of the Action (1977) and Stir Crazy (1980) – were commercial hits. Their greatest, if oblique, value was in giving sustained work to fellow black actors.

Towards the end of the 1970s Poitier moved to semi-retirement and his acting parts, including The Wilby Conspiracy and Let’s Do It Again (both 1975), were hardly satisfying. He narrated a documentary about his hero Paul Robeson and stayed off screen for several years.

In 1988 he re-emerged in a brisk thriller, Little Nikita, playing an FBI agent on the track of spies. The film co-starred River Phoenix, with whom he reunited in the enjoyable caper Sneakers (1992). The same year he also received the American Film Institute’s life achievement award – the first black actor to receive the accolade. It ushered in another busy period, including To Sir, With Love II, made for television in 1996; a portrayal of Nelson Mandela in Mandela and De Klerk (1997), also for television; and the political thriller The Jackal (1997), in which he played the FBI’s deputy director. He published two more memoirs, The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2000) and Life Beyond Measure: Letters to My Great-Granddaughter (2008).

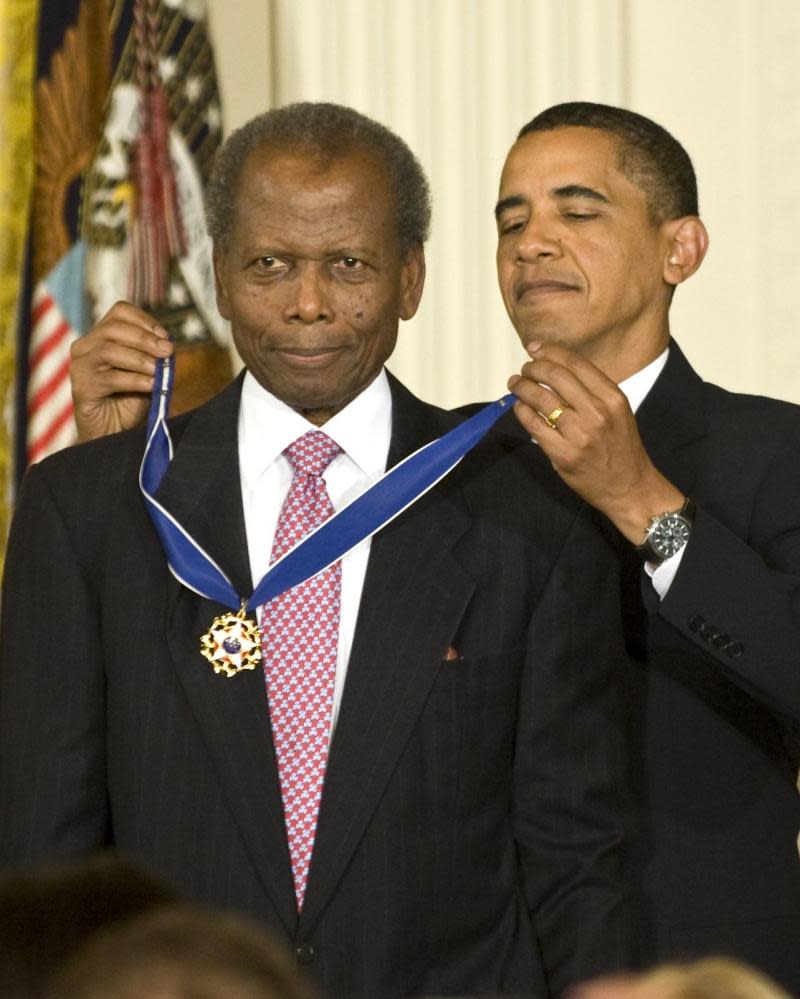

In 2002, almost 40 years after his groundbreaking Academy Award victory, he was awarded an honorary Oscar for his performances on screen and “for representing the industry with dignity, style and intelligence”. This view was echoed not only in his numerous awards for acting. In 1974 he had been given an honorary knighthood; in 2009 he received, from Barack Obama, the US presidential medal of freedom; and in 2016 he was awarded the Bafta fellowship. He also served as the non-resident Bahamian ambassador to Japan between 1997 and 2007 and was concurrently the Bahamian ambassador to Unesco.

A daughter from his first marriage, Gina, died in 2018. He is survived by Joanna and their daughters, Anika and Sydney Tamiia; and by three other daughters, Beverly, Paula and Sherri, from his first marriage.

• Sidney Poitier, actor and director, born 20 February 1927; died 6 January 2022

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies