10 best black comedies of all time, from Dr Strangelove to Withnail and I

One person’s black comedy is another’s tasteless tripe. In Bosley Crowther’s original 1964 New York Times review he described Stanley Kubrick’s Cold War satire Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb as the most shattering sick joke he had ever come across and took issue with the director’s ridiculing of the military and the presidency.

Crowther failed to recognise that the brilliance of Dr Strangelove had made these hitherto sacred cows legitimate targets for satire then and forever after. For filmmakers themselves the fine high wire act involved in balancing the boundaries of where bad taste ends and the unacceptable begins is fraught with danger.

This list of 10 essential blackest comedies includes some films that were lauded on release but also some whose quality wasn’t recognised until many years later. The contemporary reaction to them should be taken within the context of the times in which they were made.

Click through the gallery or scroll below for The Independent’s 10 best black comedies.

10. Bad Santa (directed by Terry Zwigoff, 2003)

The perfect antidote to the usual Christmas slush-fest, Bad Santa has an outrageously profane and debauched Billy Bob Thornton using his seasonal job as a shopping mall Santa Claus to rob the mall’s stores. A needy child latches on to him, thawing the misanthropic alcoholic only slightly, but Zwigoff makes no compromises, and leaves no yuletide convention unscathed. One can only guess at how many unsuspecting families have had their festive celebrations scarred after innocently viewing just a smidgen of this disgusting but hilarious monument to bad taste.

9. Monsieur Verdoux (Charles Chaplin, 1947)

Hugely controversial on release, the hostile reception garnered by Monsieur Verdoux helped precipitate Chaplin’s eventual exile to Europe. The years between 1940’s The Great Dictator and Chaplin’s most polarising film hadn’t been kind to Chaplin thanks to scandal in his private life and the increasing perception of his supposed communist sympathies. Chaplin’s subsequent feelings of isolation and alienation informed this pitch black tale of a bluebeard who woos and murders a series of wealthy women so that he can support his own family. Chaplin’s satirical social commentary and his character’s defence that his crimes paled into insignificance in comparison with the horrors of the real world found no favour either at the box office or with critics, and the little tramp’s journey from the world’s most loved entertainer to public enemy number one was complete.

8. The Heartbreak Kid (Elaine May, 1972)

Forget the wretched Ben Stiller remake and try and view a (very rare) copy of this superb comedy of embarrassment and while you’re about it, go for a double header of the oft overlooked Miss May’s work with 1971’s A New Leaf. A Jewish boy (Charles Grodin) marries a gauche young woman in haste (Jeannie Berlin) and decides to end the marriage when he falls for and woos alluring blond goddess Cybill Shepherd whilst on honeymoon, to the uncomprehending disbelief of Shepherd’s Wasp father, Eddie Albert. There are superb performances all round, with Oscar nominated Berlin (May’s daughter), a stand out. In other hands the whole premise could have dissolved into bathos, but May and screenwriter Neil Simon produced a film that is wise, funny and true, and in the restaurant scene when Grodin dumps his new bride, well... heartbreaking.

7. Withnail and I (Bruce Robinson, 1987)

A British movie that inspired a student drinking game and has its’ many hilarious lines quoted verbatim by fans (“Don’t you threaten me with a dead fish!” etc.) must have something going for it, and Withnail and I certainly does. Paul McGann and a marvellously wasted and acerbic Richard E Grant make the most of Robinson’s terrific semi-autobiographical script in this hilarious tale of two base, out of work actors living in squalor who drown themselves in a diet of booze, pills and lighter fluid on a disastrous holiday in the country circa 1969. The whole movie is basically one long bender followed by the mother of all hangovers, (“Look at my tongue, it’s wearing a yellow sock.”) and stands as a perfect farewell to the flip side of the so-called swinging Sixties.

6. Harold and Maude (Hal Ashby, 1971)

A cult favourite dismissed and panned by critics on its’ release, Harold and Maude’s reputation has grown immeasurably over the years. The story revolves around the tender romance between Harold (Bud Cort), a death obsessed 20-year-old and 79-year-old Maude (Ruth Gordon), a holocaust survivor whose joie de vivre stems from that experience. Critics and cinema goers couldn’t get past Harold’s elaborately staged fake suicides and the love story between the pair, (If it had been a 79-year-old man and a 20-year-old woman, would there have been so much resistance?), but beneath the gallows humour lies a rather warm and moving film.

5. The Ladykillers (Alexander Mackendrick, 1955)

Director Mackendrick was soon to depart for America to make the very dark Sweet Smell of Success and The Ladykillers was his final film at Ealing and a fitting swansong. Mackendrick himself viewed the film as a comic and ironic joke about the condition of a decaying post war England and the breakdown of the old order. A gang of thieves rent a room in a sweet old lady’s house (a scene stealing Katie Johnson), and masquerade as musicians while they plan and execute their latest caper. When the indomitable old lady threatens to reveal all to the police, the gang decide they have to kill her. The gang, a marvellous gallery of grotesques played by Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers, Cecil Parker, Herbert Lom, and Danny Green then have to decide who’s going to do the dirty deed but only end up offing each other in a series of gruesome but highly amusing vignettes. The movie’s plot supposedly arrived fully formed to screenwriter William Rose in a dream, and The Ladykillers remains one of Ealing’s greatest works.

4. Fargo (Joel Coen, 1996)

One of their finest achievements, and one of the standout films of the 1990s, Fargo put the Coen brothers in the major league, winning a best screenplay Oscar. Frances McDormand lifted the best actress award for her role as the heavily pregnant Minnesota police chief who hides a razor-sharp mind behind her congenial, homely persona. This quality allows the chief to piece together the convoluted tale of a kidnapping for ransom that goes disastrously wrong. Jarringly violent in places and with an other-worldly ambience, Fargo is shot full of the brothers’ trademark dark humour and lives up to its’ blurb: “a lot can happen in the middle of nowhere”.

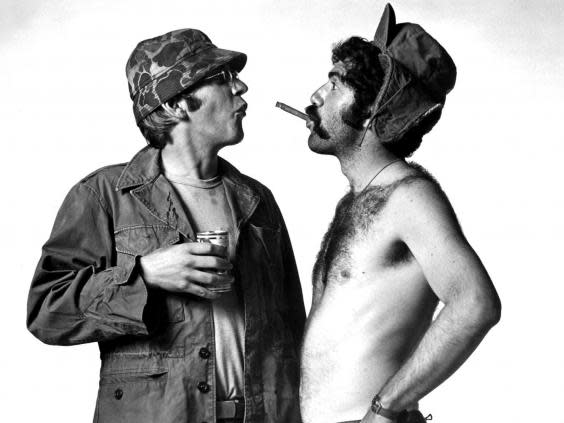

3. MASH (Robert Altman, 1970)

MASH fully deserves its’ exalted status as the landmark antiwar film of its’ time or indeed of any time. Made at the height of the Vietnam War but set during the Korean War, the parallels between the two conflicts couldn’t have been clearer. The audience was left in no doubt about MASH’s intended targets – the horrors and absurdities of war which in real life were being beamed from Vietnam into a weary nation’s living rooms, bungling military bureaucracy, the head nurse who is immune to the suffering around her, Uncle Sam, God, the whole nine yards. The outrageous practices and cruel capers perpetrated by Trapper, Hawkeye, et al on their victims, the jokes and ad libs in the operating theatre while the surgeons are covered in blood and gore, are a coping mechanism, a way of staying sane in an insane world. In other words, we laugh, lest we cry.

2. Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949)

Alec Guinness famously played eight roles in this very dark comedy of manners and is of course, brilliant, but he is matched all the way by a marvellously urbane and detached Dennis Price as the serial killer who calmly murders his way to a dukedom. The film takes barbed pot-shots at the aristocracy and the class divide and the talented but troubled Hamer directs with a sureness of touch that does full justice to the billboards declaring the film “a hilarious study in the gentle art of murder”. Price’s exquisite voiceover and the savage twist in the tail are the icing on the cake in a film with no room for sentiment or remorse, the pinnacle of Ealing’s wonderful body of work, and one of the greatest British films ever made.

1. Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

A deranged US general deliberately launches a nuclear bomb on the Soviet Union and the hapless American President (“Dimitri, we have a little problem...”) has to deal with the fallout. Possibly only Kubrick would dare make a film about a nuclear attack on the USSR while the Cuban Missile Crisis was still fresh in many people’s minds, but he created an instant classic in this justly famous and celebrated example of his dark art. Dr Strangelove boasts a wonderful screenplay by Kubrick and Terry Southern that aptly sums up the warped rationale of the so-called nuclear deterrent and has a uniformly brilliant cast, including Peter Sellers playing three roles. It is a film that has to be watched time and time again to marvel at how Kubrick finds humour in an unthinkably horrific situation and if anything, this devastating and timeless cold war satire has improved with age and is just as relevant today.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies