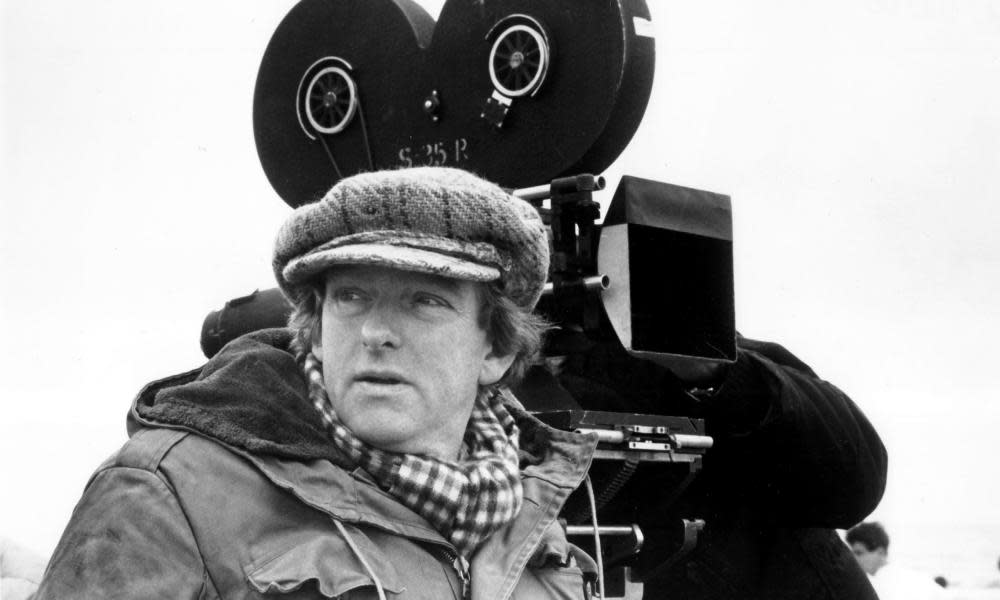

Hugh Hudson obituary

“The British are coming!” exclaimed the screenwriter Colin Welland at the Oscars ceremony in 1982, brandishing the statuette he had just won for Chariots of Fire (1981), a small-scale, factually based British sporting drama which took three further prizes that night including best picture. But the film’s director, Hugh Hudson, could only wince as he listened to the speech. “Oh Christ, Colin, why do you say these things?” he later recalled thinking to himself. “You talk too much. You’re too verbose!”

Along with his contemporaries Ridley Scott, Alan Parker and Adrian Lyne, Hudson, who has died aged 86, made his name directing stylish, expensive commercials in Britain. He estimated that he shot more than 1,500 of them prior to his big-screen debut with Chariots of Fire, which told the story of two British athletes, Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross) and Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson), who won gold at the 1924 Paris Olympics after overcoming personal hurdles; Abrahams faced antisemitism at Cambridge, where he was a student, while Liddell, a devout Christian who claimed to feel God’s pleasure in him when he ran, refused to compete on the Sabbath even when his Olympic race was scheduled for that day.

The slow-motion opening credits sequence showing runners training on the beach came to define Chariots of Fire in the minds of all who saw it, though it would not have been nearly as atmospheric without the surging electronic score by Vangelis, which Hudson had commissioned to make the film feel more modern and less like “heritage” cinema. The picture was undoubtedly stirring but it also had personal relevance for the director, who had chafed against his own privileged background.

“The film was used by Thatcherites to boost morale around the time of the Falklands conflict,” he later recalled. “But people also queued around the block to see it in Buenos Aires. They related to what it was really saying: stand up for yourself in the face of the establishment hypocrisy. I think David Puttnam [the producer] chose me because he sensed I’d relate to the themes of class and racial prejudice. I’d been sent to Eton because my family had gone there for generations, but I hated all the prejudice.”

His follow-up was a thoughtful, elegiac take on the Tarzan story, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), which continued the anti-establishment theme of Chariots of Fire by showing a hero at odds with upper-class society. “I hope it conveys the inhibiting limitations of a code of behaviour, a notion of masculinity, that can be traced to schools like Eton,” he said. “That code insists that it’s unmanly to give in to emotion.” In Tarzan, Hudson saw echoes of himself: “He rejects his background. Half of him is the Earl of Greystoke and the other half is wild … I was a rebel to my family. I just didn’t like elitists.”

Production was beset with difficulties. Hudson fought bitterly with Warner Bros over the running time; the veteran screenwriter Robert Towne was so unhappy with the movie that he removed his name from it (the Oscar-nominated script was credited to PH Vazak, after Towne’s dog); and Glenn Close re-dubbed the entire performance of the newcomer Andie MacDowell after Hudson decided her southern twang was wrong for the film.

Those travails were nothing compared to the reception that greeted Revolution (1985), his epic about the American war of independence. Hurried into release by its beleaguered production company, Goldcrest, there was no element of it – from the confused storytelling, the perfunctory love story, the location work (Norfolk stood in for New York) and a central performance by Al Pacino generally considered anachronistic – that was not excoriated by critics. A review in Time Out called it “an almost inconceivable disaster… a cortege of fragments and mismatched cuts,” and ended by asking: “Director? I didn’t catch the credit. Was there one?”

In time, Hudson came to be sanguine about the experience. “The scorn heaped on my film was painful but perhaps right – it was incomplete and that has rankled with me and Pacino ever since.” A new cut, with narration by Pacino (“It’s his current voice, much gruffer than his voice in the film”) as well as some minor re-editing, was more warmly received when it emerged in 2008. “Revolution was misunderstood and unjustly treated on its first appearance,” wrote the Observer film critic Philip French. “Seeing it again in the director’s slightly revised version, it now strikes me as a masterpiece – profound, poetic and original.”

Related: Hugh Hudson: smash-hit pop classic Chariots of Fire director was a hero of British film

Hudson was born in London to Jacynth (nee Ellerton) and Michael Donaldson-Hudson, an insurance broker; the couple divorced when he was eight. After Eton, Hudson did his national service and then trained as an editor in Paris in the late 1950s and early 60s. Back in London, he made a series of documentaries before moving into directing commercials, many of them for Ridley Scott Associates. He founded his own production company, Hudson Films, in 1975.

He was second-unit director on Midnight Express (1978), Parker’s sensationalist story of life in a Turkish jail, and enjoyed his greatest triumphs in advertising around that time. For Courage Best Bitter, he staged a black-and-white pub scene set to Chas & Dave’s hit single Gertcha and shot by the great cinematographer Robert Krasker, whose credits included The Third Man (1949). He directed the Cinzano aeroplane encounter between Leonard Rossiter and Joan Collins, as well as many of the elliptical Guinness ads with Rutger Hauer. His most acclaimed ad showed robots in a Turin car plant building Fiat Stradas to the strains of Figaro’s Aria from Rossini’s The Barber of Seville; the novelist JG Ballard singled it out as his favourite commercial of all time.

Hudson was inundated with awards for his advertising work – he won six Cannes Golden Lions and two Grands Prix – but the move to features could not come soon enough. “To me it was like being let out of prison, frankly. I felt I was in clover.” Nevertheless, he returned intermittently to advertising, and made several influential campaign films for the Labour party, including one in the runup to the 1987 election, which came to be known informally as Kinnock the Movie, and which raised the Labour leader’s personal poll rating by 19 points.

Following the catastrophe of Revolution, Hudson completed only four further full-length features: the thriller Lost Angels (1989); My Life So Far (1999), based on Denis Forman’s memoir about his childhood in Scotland before the first world war; the drama I Dreamed of Africa (2000), starring Kim Basinger; and the historical adventure Finding Altamira (2016) with Antonio Banderas. He also made a television documentary, Rupture: A Matter of Life or Death (2011), about his wife, the actor Maryam d’Abo, and her recovery from a brain haemorrhage. In 2012, he co-produced a well-reviewed stage version of Chariots of Fire. His final credit was as screenwriter of The Tiger’s Nest (2022), an adventure about a boy who saves a tiger cub from poachers in the Himalayas.

He is survived by d’Abo, and by his son, Thomas, from a previous marriage, to the artist Susan Michie, which ended in divorce.

• Hugh Hudson, director, born 25 August 1936; died 10 February 2023

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies