Fargo review – Coen brothers’ snowbound noir is still a work of gleaming brilliance

Now rereleased for its 25th anniversary, Ethan and Joel Coen’s perfectly flavoured comedy-thriller Fargo has become an established classic noir. Or maybe noir-blanc, a tale of criminal wickedness and weakness in the vast, snowy-white landscapes of Minnesota and North Dakota. Since 1996, something in Fargo’s macabre black comedy – the Garrison-Keillor-meets-James-M-Cain approach – has proved fertile: it inseminated a streaming-TV property now spanning four seasons. But the original film now looks better than ever, and it’s down to its keeping the quirkiness relevant and in check (something the Coens maybe haven’t always been able to achieve), and its brilliance in making the forces of law and order look as interesting and funny as the bad guys.

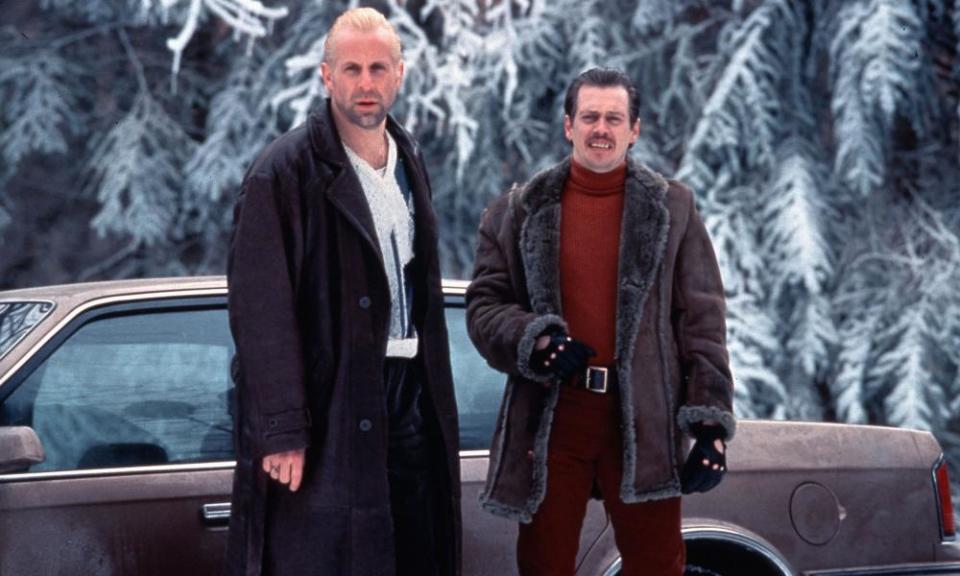

There is an outstanding performance from Frances McDormand as Marge Gunderson, a seven-months pregnant chief of police investigating the brutal slaying of a state trooper and two locals. These people have been killed by two grotesquely incompetent hoodlums, Carl (Steve Buscemi) and Gaear (Peter Stormare), who were hired by weak and greedy car salesman Jerry Lundegaard, superbly played by William H Macy, his great, plaintive blue eyes radiating self-pity and impotent resentment. Jerry had engaged these guys to kidnap his blameless wife, Jean (Kristin Rudrüd), so that Jerry’s wealthy father-in-law, Wade (Harve Presnell), would spring for the million-dollar ransom, which Jerry would secretly collect for himself, allowing his two crooks a modest fee.

Marge Gunderson is the very image of midwest decency and modesty, blooming with health and friendly openness – though she is also a brilliant detective with great intuition and procedural sense, entirely unfazed by the ugliness and violence of the case. In one scene, the Coens show that she is almost ready to give Jerry the benefit of the doubt, despite his guilty manner, because, with his dorky love of golf, Jerry doesn’t appear so very different to Marge’s great big lovable lunk of a husband, Norm (John Carroll Lynch). Marge has her own impregnable core of innocence and is still capable of being shocked. When old school friend Mike Yanagita (Steve Park) contacts Marge and starts coming on to her, Marge is stunned by what she finds out about him. This movie is a noir but there is no cynicism; Marge sees the very worst that human nature has to offer, but doesn’t become a wisecracking seen-it-all shady lady; she is still entirely fresh, and her pregnancy, that hope for the future, is uncompromised.

Fargo is speckled with those ironising tics that keep us off balance: after one strained conversation in a diner, a parodically perky young woman at the till asks: “How was everything today?” and the question jars and crashes; she is like a figure from a bad dream. The Coen style is so difficult to pin down here. The witnesses that Marge interviews describe Stormare’s character as “funny looking” without being able to say why, and trying to describe this film’s tone raises the same difficulty.

It is the piercing whiteness of the snow that is Fargo’s design motif and moral universe. The people thereabouts may be warm but the weather is deathly cold and forbidding, with that vast featureless landscape eerily disclosed in various overhead shots. The snow can reveal the wrongdoer (Marge importantly finds incriminating footprints in it) but it also covers up the crime: the snow is where Carl wants to bury his ill-gotten share of the loot. Snow is associated with virginal innocence, but the snow of Fargo is drenched with guilt. David Lynch might have told the story of Fargo by making it unsolved and insoluble; Quentin Tarantino might have explained the sudden spasms of violence by making the culprits ingest a lot of cocaine or crack. The Coens make it more realist and more humanly sympathetic, and McDormand is perfect in the role.

• Fargo is released on 11 June in cinemas.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies