'Gladiator' at 20: Creator David Franzoni on the film's journey from 'Easy Rider' homage to Oscar hit (exclusive)

It was nominated for twelve Oscars, winning five, made £370million at the global box office and along the way re-ignited a genre and turned Russell Crowe into a megastar.

Twenty years later, with the film celebrating its anniversary on 12 May we speak to cast, crew and fans about Gladiator.

The beginning

It was shot in 1999 and we’re now celebrating its 20th anniversary, but Gladiator actually started being written in 1972. It was back then that a young David Franzoni dropped out of graduate school and decided to ride east across Europe on a motorbike.

“Everywhere I went in Europe there were arenas,” he remembers now. “Even as I went east, going through Turkey, I began to think to myself this must have been a hell of a franchise.”

Read more: Nick Cave shares details of his Gladiator 2 script

He ended up in Iraq, where he swapped his book on the Irish Revolution with another girl’s novel, a pulpy story about Roman gladiators called Those About To Die by Daniel P. Mannix.

“I had the idea for Gladiator while I was in Baghdad,” he explains. “And I swore if I ever became a screenwriter, I’d try to get it made.”

Gladiator gets off the ground

Cut to 25 years later and Franzoni was a Hollywood screenwriter with a deal at Steven Spielberg’s Dreamworks, busy working on the director’s historical drama Amistad. The movie was shooting in Rome and at a local library, Franzoni started reading more about the city’s history. The idea which had lain dormant for so long returned. Thanks to their strong working relationship, he pitched it to Spielberg.

“He just said, ‘go write it’, so I did.”

The original Gladiator script was based more in history than the finished movie, with a hero called Narcissus (who killed Emperor Commodus in real life), Lucilla (Connie Nielsen) being executed midway through and lots else. But the bones of what we would end up seeing was there – the hero died, as did his mentor Proximo (Oliver Reed) along with the fundamental thrust of the film. “The dynamic of the picture is: Commodus had the guy he wanted to kill in his grips, or did that guy have him in his grips? That was the power of the movie,” says Franzoni.

For the writer, it was essentially a man versus machine narrative straight from the Sixties and Seventies. “The scene with Maximus running his hand over the top of the grass is right out of Easy Rider,” he says.

Read more: Iron Man 2 at 10: What went wrong?

Indeed, once Ridley Scott came onboard (something that happened remarkably quickly, but then as Franzoni says, “Ridley was the dream choice, but when you’re working with Steve Spielberg, those dreams just sort of come true”), the kinds of references they were discussing were films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Bertolucci’s The Conformist.

Finding the actors

Casting began, with the supporting cast filled out with iconic English character actors like Richard Harris, Oliver Reed and Derek Jacobi. Joaquin Phoenix, then trying to navigate his way from child to adult actor scooped the role of the callow, bitter Emperor Commodus.

“My wife and I will never forget the day they sent over Joaquin’s audition tape,” recalls Franzoni. “Because everyone was like, ‘Joaquin Phoenix, isn’t he some kind of stoner surf kid?’ The audition tape was a knockout. It was mind-boggling.”

Meanwhile, although Mel Gibson and even Antonio Banderas were mentioned, Russell Crowe was at the top of the list to play Maximus thanks to his breakthrough performance in LA Confidential.

Still, according to Franzoni, who was on board as a producer as well as writer, “There were a couple of actors that Steven felt he needed to go to because of his relationship with them. And we were all sort of hoping they’d say no.”

One of those was apparently Tom Cruise.

‘There are problems with the script’

Nevertheless, Crowe got the part, production geared up and in true Hollywood fashion, that’s when everyone decided there were issues with the script. American playwright John Logan did a rewrite, as did British writer William Nicholson, while Franzoni rewrote his original draft.

Part of the problems stemmed from some of the unorthodox elements to the script, from the death of the lead character to the fact executives couldn’t understand why Commodus wouldn’t just kill Maximus the moment the latter took off his mask in the arena. Some even advocated for Crowe keeping his mask on throughout.

“I think [that] was settled by Steven basically sending a memo,” laughs Franzoni. “One day everybody was just on-board and it certainly wasn’t because of me!”

Read more: Russell Crowe reveals career regret

The script confusion meant that this huge movie, with thousands of extras, massive sets, international locations (the opening battle was in England, the gladiatorial school in Morocco and Rome was mostly recreated in Malta) and a $103 million dollar budget started shooting without a finished story.

“We had 21 pages when we started shooting,” Crowe told Radio 1 in 2016. “It’s the dumbest possible way to make a film. At one point in time, Ridley gave the crew the day off because we simply didn’t know what we were going to shoot the next day.”

Often, a brain trust of Crowe, Scott and Franzoni would sit together at the end of the day with cigars and whisky and look at the other writers’ contributions, taking what they liked and deciding the rest themselves on the fly.

“The other writers did great work, we all worked hard on it,” says Franzoni. “Everybody added crucial stuff…but the soul and the root of the movie had to get back on track and it did.”

But this collaborative process is also how some of its iconic lines came about. Looking for something macho to say instead of goodbye, Crowe remembered his high school motto, which was Veritate et Virtute, or Truth and Honour. “I remembered that school motto and I converted it, and I said it to [Ridley] in Latin,” the star told Inside The Actor’s Studio.

“And he sort of raised an eyebrow and he took his cigar out of his mouth and goes, ‘what's that mean, then?’ I said, uh, ‘Strength and Honour’ and he goes, ‘Say that.’”

Building and shooting Gladiator

Ralf Moeller, who plays fellow gladiator Hagen, admits that “Russell sometimes got frustrated” with the frenetic shoot, but that they were always friendly fights and there was a strong camaraderie on-set.

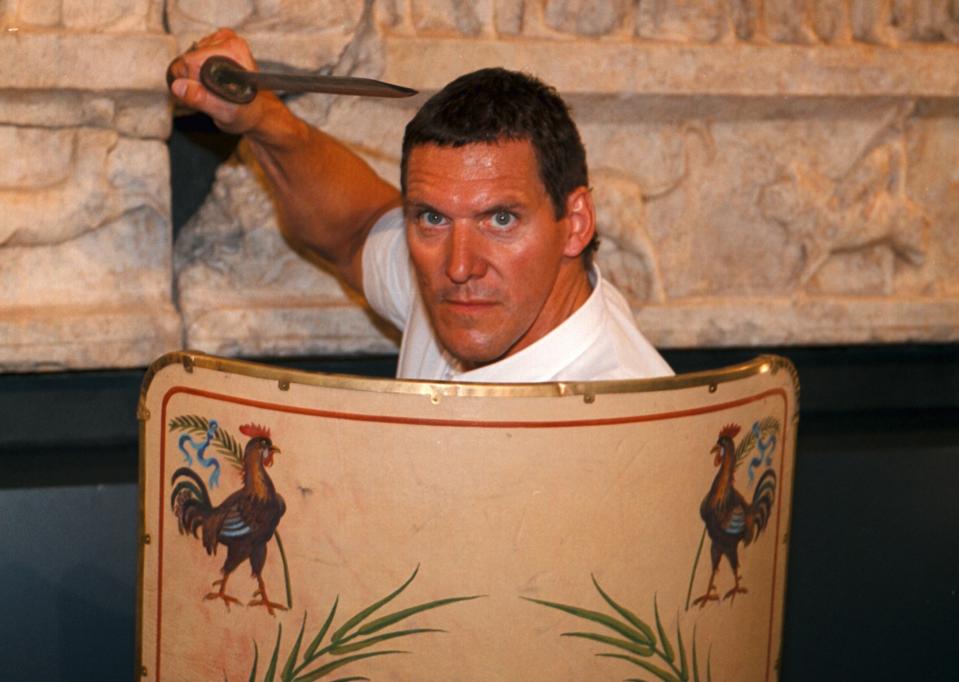

“Russell was very protective,” says the 6’6” German-born actor and former Mr Universe, who got the job after appearing as Conan in a TV series and would work out with Crowe and co-star Djomin Hounsou every morning in a tent kitted out with gym equipment that was transported wherever they went. That bond was needed on such a large project with so many moving parts and so much action.

“I remember one scene, it was really hot,” says Moeller. “I had to run across the arena from one side to the other. It took hours before we came to this scene. Suddenly, it was my part to run and the moment I started, I got cramp in my calves and fell down because I didn’t drink enough water. Russell and Djimon came to help get the cramp out.”

Of course, it is those spectacular arena sets, the huge battles and a gigantic Coliseum that’s actually much bigger than the real thing and was built on the remains of a British fort in Malta, which gives Gladiator its scope and grandeur.

“The reason it worked is because he built the real thing,” says David Franzoni of the film’s provincial gladiator school which was constructed in Morocco. “When you drove up to it, it looked like it was part of the city. The Bedouin would come in from the desert to watch the shoot and so Ridley just put them in the movie. It had this legitimacy to it that happened naturally.”

Bestselling author Tom Holland (Dominion) had just started to write Rubicon, his popular history of Rome, when the movie came out.

“The Coliseum is much, much larger than the reality. But that’s fine, because the Coliseum would have been overwhelming. People would have never seen anything on that scale. We’re so familiar now with towering buildings. The unreality of the Coliseum is what makes its impact real.”

In fact, he thinks those who pick up on all the historical inaccuracies in the film (the armour, the weapons, the real-life characters in the movie and the arena fights themselves all take huge dollops of creative licence) are going about it the wrong way.

“We don’t know what it was like to live in Rome. We don’t know what it was like to fight in a battle,” he explains. “The documents that tell us what it was like are often creative works of literature. If you obsess with getting every detail right, you’re not being true to the spirit of antiquity.”

‘People thought we were out of our minds’

But while the chaotic shoot generally happened out of the public eye, there was one big problem which Scott and company couldn’t avoid everyone hearing about.

“Ridley really fought for [Oliver Reed],” says Moeller. “He went later to Oliver and said, ‘look, they didn’t want you, but I want you – don’t let me down!’ And he never did until he died three weeks before the movie ended.”

David Franzoni had killed Proximo in his original draft, but the character had subsequently been resurrected in later versions of the screenplay. So when Reed died on 2 May, 1999 during a drinking competition with a group of British Navy sailors before he had shot all of his scenes, a radical rethink – and some still-nascent technology – was needed.

Read more: Movies that brought actors back to life

“Right from the start, the script was designed to end in the deaths of Proximo and Maximus,” says Franzoni. “The question was, why keep Proximo alive if we were going to kill Max? While that debate was going on, Oliver had his fatal drinking bout with the crew of a British destroyer in Valletta. But the argument didn't go away. Finally, Ridley and others decided that, dramatically, Proximo needed to die.

“This was because the gratuitous murder of Proximo set up the final confrontation between Max and Commodus. I designed Proximo to be a second Marcus Aurelius, so when Commodus has him killed, he's killing Marcus Aurelius all over again. But there was also the issue of how to digitally keep Proximo alive, when the results were considered questionable. So we have one ‘virtual’ Proximo scene, the night he's killed. And whether everyone understood how it was dramatically necessary, they get it right.”

The death of Reed must have exacerbated the feeling many back in Hollywood had that Gladiator was spiralling out of control. Early in pre-production, Spielberg had suggested they use a fake name while shooting (he suggested The Hot Rod Project) as he was worried others would catch on to what they were doing and shoot their own knock-off Roman actioner.

But three quarters of the way into the shoot, the idea that anyone would try and capitalise on the film seemed increasingly laughable to the execs.

“A lot of people thought we were making Conan 3,” says Franzoni. “They had no idea what the hell we were doing. In fact, somebody suggested that perhaps we had Schwarzenegger as the big gladiator with the tigers. The other level was that we were out of our minds and shooting a terrible, horrible sword and sandals movie that nobody would go see.”

Not even the stars were immune. “Russell, until he saw the final cut, he thought it was the end of his career,” says the writer.

“That’s my impression. I guarantee you he was really worried.”

Showing it to the public

As we know, it turns out all the naysayers couldn’t have been more wrong.

David Franzoni remembers a meeting with a circumspect Ridley Scott having just watched some of the dailies at Dreamworks.

“[I told him], look I just saw this rough cut, with music from like The Bee Gees or something to fill in, if you release that you’ll have a hit.”

Read more: Author slams LA Confidential movie

“There were two films all through my childhood that I really wanted to watch,” says historian Tom Holland. “One was a really good dinosaur film and the other one was a really good Roman film. My yearning for a really good dinosaur film was satisfied with Jurassic Park. The second greatest cinematic experience of my life was watching that opening battle [in Gladiator].”

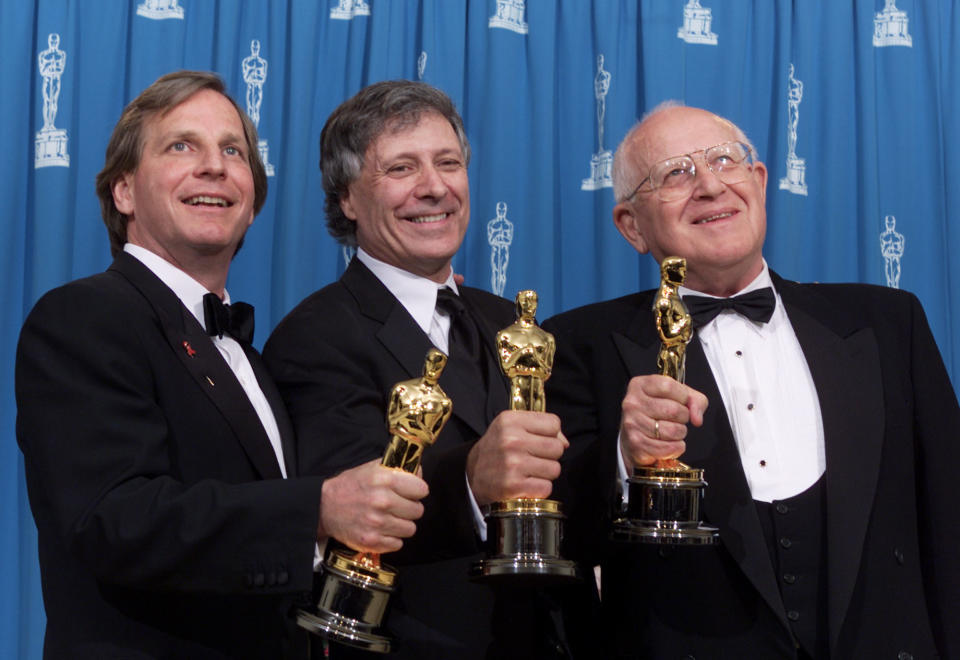

The film was nominated for 12 Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Original Screenplay, Best Supporting Actor and Best Cinematography.

“When it got the Oscars, I pretty much knew we were going to win for Best Picture,” says Franzoni. “I was really depressed that Ridley didn’t win for Best Director, I didn’t get that.”

He recalls seeing Russell Crowe and Joaquin Phoenix mucking around with each other in the audience, Crowe joking that the Americans would give the award to Tom Hanks rather than him. He was wrong.

“The icing on the cake was when Russell won,” says the screenwriter, “because Russell had been so worried about everything.”

Its legacy…and a sequel?

Twenty years on and the movie still resonates.

“You get recognised everywhere,” says Ralf Moeller. “Because people see [it] so many times.”

Historian Tom Holland still enjoys the way it uses the ancient world to speak about modern issues. “What that opening sequence is doing is riffing on Vietnam,” he says. “You’ve the napalm and everything and people coming out of the woods. And that’s great. It’s setting up those echoes and reverberations between America and Rome that’s always been part of how Rome’s been understood. People have always seen it as a mirror held up to our present.”

As for a sequel? Well, there was Nick Cave’s infamously bonkers follow-up script, but now another idea is in active development. Scott – who’s returning to the director’s chair – has previously intimated it would bring Crowe back, while other rumours suggest it would focus on a grown-up version of Commodus’s nephew Lucius (played by Spencer Treat Clark in the original).

Either way, it looks like Maximus could well be having his vengeance on the box office yet again.

For its creator David Franzoni though, the reason Gladiator has stuck with us is very simple.

“It is,” he says, “about a man just trying to get home.”

Gladiator is streaming on NOW TV.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies