Here's how Longlegs did Maika Monroe dirty

Note: major Longlegs spoilers follow

Longlegs is a terrific movie, especially if you like low-lit pine-panelled rooms. Have you seen it yet? If not, maybe read something else for now, because we're going to spoil the ending in a bit.

The conversation before, during and after the film has mostly – and rightly – been about Nicolas Cage's transformative performance as the suspected serial killer of the title. It's a truly remarkable showcase, and we wouldn't take anything away from it.

While some have criticised Cage's role as grotesque or grandstanding, we'd argue that he and writer-director Oz Perkins actually callibrated the performance finely to the needs of the film. Far from being a scenery-chewing fiesta, it's in fact a very precise execution of a very precise brief.

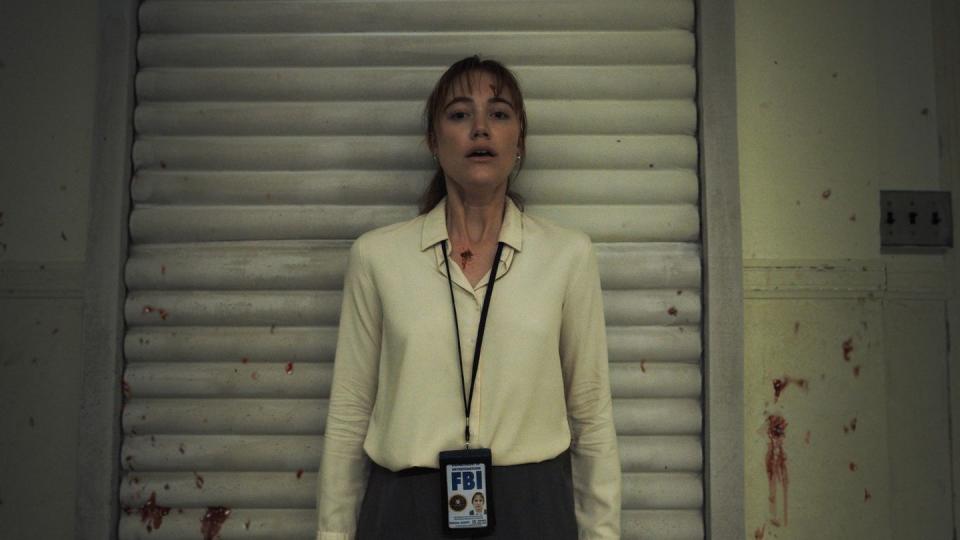

Our problem – and it's more in the spirit of starting a conversation than making a complaint – is that the plot and characterisation choices made by Perkins resulted in Maika Monroe's FBI agent, Lee Harker, being almost completely eclipsed by the rest of the film.

The protagonist of a movie doesn't have to be a showy role. Stillness is, after all, a correct balance for flamboyance. There's a long line of superstars stretching from Gary Cooper to Harrison Ford who knew how to do absolutely nothing to devastating effect.

But having said that, Lee Harker's psychic/intuitive agent isn't just a still centre working as the counterpoint to Cage's outsize antagonist, she's almost a complete blank.

That's not a criticism of Monroe. She's a great actor who has made really interesting choices in films like The Guest, Watcher and It Follows. But until the final scenes, Harker – for plot reasons – has no backstory apart from a strained relationship with her distant mother.

She has no interests apart from her desire to crack the case. She has no relationships except for that with her mentor Agent Carter, who is permanently bemused by her lack of affect and effectively has to act towards her like a parent with a gifted but socially awkward child.

She doesn't express opinions, she doesn't seem to care about anyone except in the abstract, she doesn't like or dislike anything, she doesn't want anything except clues, she barely speaks to anyone.

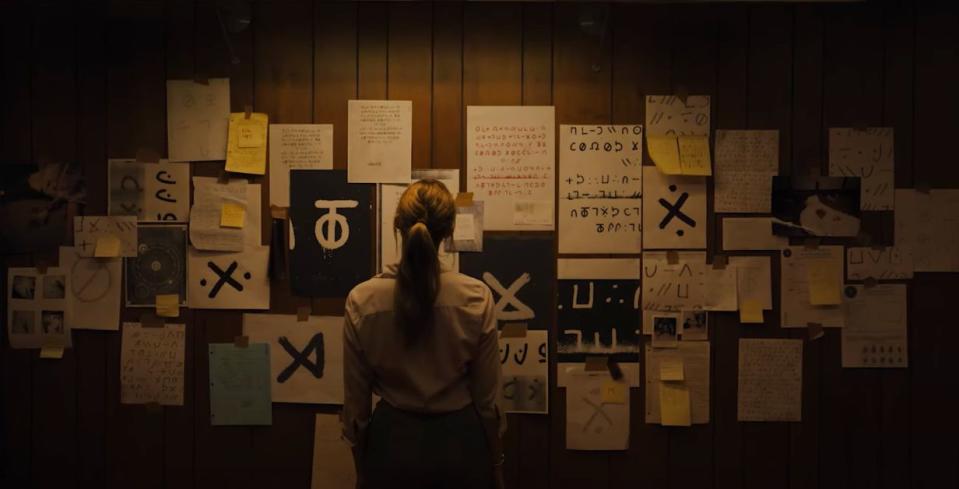

Monroe plays her as autistic-coded, which is certainly how the role seems to have been written: she appears uninterested in social interaction, avoids eye contact, hyperfocuses on codes and systems and has exceptional affinity with patterns. (Monroe herself says she drew inspiration from The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo's Lisbeth Salander.)

It's a perfectly valid choice and neurodivergent commenters have recognised much truth in her characterisation. In the scene where Carter's daughter invites her to her birthday party, Lee's literalness and physical disengagement are played for laughs, turning this into a vital moment in humanising her.

But that one moment is all our heroine gets.

Because so much about her is withheld until the big reveal – basically, that her mother has done a deal with Satan's pouchy-faced minion and allowed him to live for decades in the family basement, his supernatural powers effectively wiping Lee's memory – she barely exists in the film at all except as a chess piece, an object for the camera to follow as the plot unwinds.

Her problem-solving gifts and diligence are rendered meaningless by the reveal. The script lays down some hints that "solving" the case isn't as important as audiences might expect, by skimming over the Zodiac-like code and stressing Harker's apparent psychic powers, but when we find out it was Beelzebub All Along, then Harker's agency, already flimsy, is taken away at the knees.

She doesn't catch Longlegs – he gives himself up. She doesn't get to kill him either – he kills himself. She doesn't solve the mystery – her mother confesses all in a long info-dump that implies Harker is the way she is because a devil-doll in the basement has been suppressing her inquisitiveness and memory since childhood.

All she gets to do in the end is explode her suppressive doll's skull and save Carter's daughter (for which thank heavens).

Some of the discourse around the film argues that it can be read as a metaphor for child abuse: Lee's mother invites a predator into their house and the grown-up Lee's behaviour – repressed memories and all – is commensurate with PTSD.

Oz Perkins has said on record, however, that the film is a mood first and foremost, and that his chief narrative interest was the things parents conceal from the children and the effects of that concealment. (His father, Psycho actor Anthony Perkins, was a closeted gay man who undertook 'conversion therapy'.)

All these interpretations – and, of course, the third act reveal – help to justify the blankness of Lee Harker for the first two acts of the film. But for those two acts, while the audience is wrestling with such an oppressively magnetic offscreen presence as Longlegs, they need something to occupy the foreground, and no amount of retroactive plot reframing at the last minute can undo that absence.

Maybe it's a completely different experience on second viewing and we'll eat our words. We can't wait to find out.

Longlegs is available to watch in cinemas now.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies