Kermode on… Nicolas Roeg: ‘Nothing is what it seems’

This month marks 50 years since the release of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, a personal touchstone movie (adapted from a story by Daphne du Maurier) that is at once an occult chiller, a poignant portrait of married love, a heartfelt meditation on grief and a shaggy dog story with a grisly sting in its tail. The anniversary offers film fans an excuse to dust off this classic, alongside other hallowed 1973 movies such as Enter the Dragon, The Exorcist and The Wicker Man, which was originally the supporting feature for Don’t Look Now (how’s that for a double bill). It also allows me to kick off my new column, focusing each month on a different director, with a few thoughts on Nicolas Roeg, the great British director who once told me that time was “lateral rather than linear”, rendering the very concept of anniversaries irrelevant.

In Roeg’s films, which range from the galaxy-traversing sci-fi of The Man Who Fell to Earth to the imagined Einstein/Monroe relativity of Insignificance, time is fluid – a mysterious memory pool where past, present and future collide. It’s no coincidence that Roeg’s most notorious film (which I’ve introduced on BFI Player) was a non-linear, flashbacked psychodrama from 1980, tellingly titled Bad Timing.

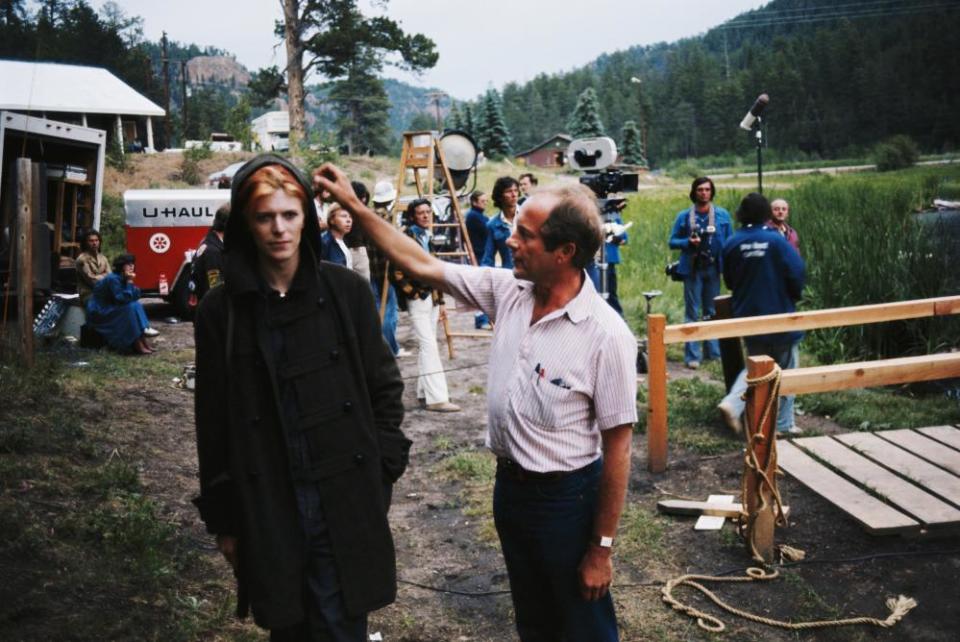

Roeg cast David Bowie as the starman after seeing him in a BBC documentary and thinking he looked like an alien

Roeg began his movie career as a camera operator and cinematographer, serving second unit on David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia and conjuring the signature, dazzling sword-flashing sequence in John Schlesinger’s Far from the Madding Crowd (1967). In 1970 he shared directorial credit with Donald Cammell on the psychedelic thriller Performance (tagline “Vice. And Versa”), a diehard cult favourite (it blew my mind as a student) in which a gangster and a rock star, played by James Fox and Mick Jagger respectively, find their identities blurring and melding.

Edited elliptically by an uncredited Frank Mazzola, Performance languished unreleased for two years (it was made in 1968) while distributors and censors worried about its meaning and its outre content. According to popular legend, a bathing scene featuring Mick Jagger, Anita Pallenberg and Michèle Breton caused one outraged executive to comment that “even the bathwater was dirty”.

Roeg built upon the elusive, elliptical qualities of Performance in Walkabout (1971), a freeform adaptation of James Vance Marshall’s novel about an Indigenous Australian boy (brilliantly played by David Gulpilil) guiding a teenage girl and her younger brother who have been abandoned in the outback. Temporal jumps and reversals turned a straightforward narrative into a dreamy meditation on “the most basic human themes; birth, death and mutability” – themes that would find their apotheosis in Don’t Look Now, one of my favourite films of all time (Pino Donaggio’s score is rarely off my headphones), in which a married couple in Venice are haunted by visions of their drowned daughter.

When I spoke to Roeg in 2007, around the release of his final feature, Puffball (from Fay Weldon’s novel; only available on DVD), he described Don’t Look Now as being about a couple who “have today, and yesterday, and suddenly something happens that they hadn’t planned on doing tomorrow”. He also took delight in recalling how he had cheekily put “the very premise of the film” into the mouth of Donald Sutherland’s character, John, in the opening sequence. Discussing the nature of curved water with his wife, Laura (Julie Christie), John remarks that “nothing is what it seems” – a line Roeg told me he got Sutherland to repeat “around 30 times” in an attempt to make it sound casual rather than portentous.

Very little is what it seems in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), an adventurous interpretation of a sci-fi novel by Walter Tevis, whose other filmed books include The Hustler, The Color of Money and The Queen’s Gambit. Roeg cast David Bowie as the starman who crosses the universe in search of a drink (and winds up a drunk) after seeing him in the BBC documentary Cracked Actor and thinking he looked like an alien eyeing a hostile world through the windows of a limousine. Bowie lived and breathed the character of Thomas Jerome Newton, and used images of himself from the film on the covers of two of his most celebrated albums, Station to Station and Low. The movie (which I saw at the height of my own Bowie mania) brilliantly juggles different realities, flashing back and forth in time, with mirrored relationships playing out in this world and the next.

In 2019 I was honoured to host a BFI Southbank memorial tribute to Roeg, who had died the previous year aged 90. Friends and colleagues celebrated his kaleidoscopic life and career – from documentaries such as Glastonbury Fayre (1972) to the hit Roald Dahl fantasy adaptation The Witches (1990) and beyond. Today, Roeg is regularly cited as a key inspiration by film-makers such as Carol Morley and Ben Wheatley, and is credited with pioneering a cinematic vocabulary (he likened film-making to Van Gogh painting sunflowers) that pierced the apparently solid surfaces of time and space. You may think that Roeg is gone, but, as his films continue to show us, nothing is what it seems.

All titles are available to rent on multiple platforms unless otherwise specified

What else I’m enjoying

The Bowie Lounge

I spent last Saturday night cheering and singing along to this Cornwall-based, Bowie-inspired collision of music, painting, dance, theatre and cabaret, as they returned to the stage with a new show, Space Face. It was a joy! For a decade they’ve been keeping Bowie’s experimental spirit alive. Keep your ’lectric eye open for future gigs.

Pod Save America

As the US’s most significant/terrifying election looms (Democracy v Disaster), this podcast is one of the few things keeping me sane, with former Obama aides Jon Favreau, Jon Lovett, Dan Pfeiffer and Tommy Vietor offering an insightful, informative and often hilarious guide through the madness.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies