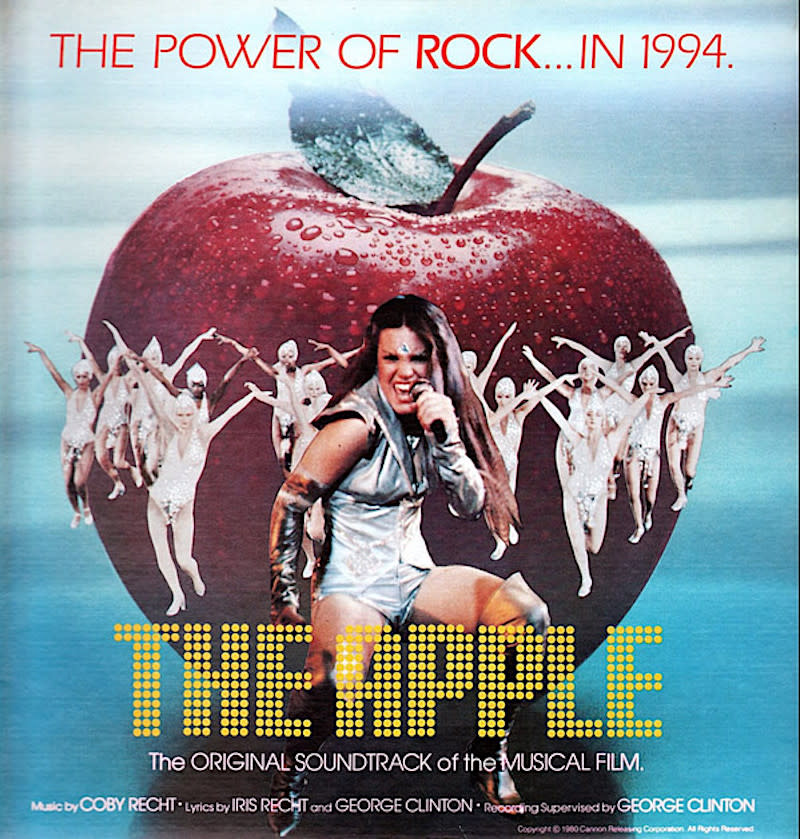

Nigel Lythgoe looks back on disastrous disco film 'The Apple': 'A very, very strange atmosphere throughout'

“So, I’m a little scared. I’ve been told you want to talk to me about” — dramatic pause — “The Apple,” gulps Nigel Lythgoe.

Lythgoe is best known as the producer of hit TV talent competitions like Popstars, American Idol and So You Think You Can Dance, so it’s understandable that he’s hesitant to discuss the anniversary of one of the lesser-known and less illustrious credits on his IMDB page: The Apple, the so-bad-it’s-amazing biblical/sci-fi rock opera for which he masterminded the outlandish disco choreography.

Clearly Lythgoe has moved on, even though The Apple (also known as Star Rock) has achieved cult status since it came out in the U.S. on 21 November, 1980 — a development that both amuses and confuses him. It’s considered by many critics to be one of the worst films of the 1980s, or maybe even of all time.

It was a box-office disaster that made other nearly career-killing ‘70s/‘80s movie musicals, like the Village People’s Can’t Stop the Music, the Bee Gees and Peter Frampton’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and Olivia Newton-John’s Xanadu look like Citizen Kane.

Read more: GoldenEye at 25

“My friend John Farrar co-wrote the music for Xanadu. We met much later, in the 1990s or 2000s, and the one thing we had in common was Xanadu and The Apple are a double-header of the worst two musicals ever,” Lythgoe laughs.

Watching The Apple now, it’s almost impossible to comprehend that a film so ridiculously shameless and plotless ever got made in the first place. But Lythgoe is quick to point out, “We must remember, this was the ‘70s. [Filming took place in 1979.] It was very strange making the movie, because we brought over something like 40 English dancers.

“We were in Berlin and we had a German electrical crew, and then an Israeli production team, and we were making the movie in a factory that actually made gas during World War II. So, it was a very, very strange atmosphere throughout.”

And perhaps not everyone in that gas factory was in his or her right mind, which could also explain a lot. “Because you could buy regular drugs over the counter in Berlin, the dancers were finding all different things — speed and Benzedrine and poppers and everything else. You could just buy it over the counter,” Lythgoe recalls.

“It was like herding cats, trying to get those dancers together. Yes, it was a strange 1970s experience.”

Adds Lythgoe, a little more seriously, “I mean, it’s laughable now. And it’s fun to make fun of it. But at the time, it was really, really depressing on some days. Very, very stressful. It was not such a pleasant process, making that film. It wasn’t pleasant memories, let’s just put it that way.” When asked if he has any pleasant memories of working on The Apple, he simply answers, “Finishing it.”

What makes Lythgoe’s Apple involvement notable — besides the fact that after this sole cinematic choreography credit, his career not only rebounded, but thrived — are the strong parallels between The Apple’s plot and, well, American Idol.

The Menahem Golan-directed rock ‘n’ roll fable is about two talented small-town innocents (Alphie and Bibi, the latter played by Catherine Mary Stewart, who also managed to emerge professionally unscathed) who compete in the 1994 Worldvision Song Festival. (Yes, 1994 — this was “The Future,” you see. Lythgoe and the rest of Apple crew apparently didn’t predict that grunge was going to happen.)

Eventually, the naive Alphie and Bibi sign a deal with music business villain Mr. Boogalow’s BIM (Boogalow International Music), only to find themselves trapped in a space-age underworld of druggy debauchery, exploitative record label contracts, and cheesy disco-dance sequences.

Gee, that sounds like the saga of quite a few Idol finalists, doesn’t it? And Mr. Boogalow doesn’t seem all that different from, say, Syco Records’ Simon Cowell. Could it be that maybe, just maybe, Lythgoe took inspiration from The Apple when pursuing his later, much more successful showbiz ventures? Perhaps it’s no coincidence that in 2000 — not long after the year that The Apple’s fictional singing competition was supposed to take place — he launched the TV talent show Popstars in Britain. And thus, life imitated art... if The Apple can be called “art,” that is.

While the Apple/Idol similarities aren’t lost on Lythgoe, he laughs off any grand conspiracy theories that one predicted the other. “There were a lot of singing competitions going on at the time,” he shrugs. “So, it never really hit me that the ‘search for talent’ was Popstars and Pop Idol and American Idol, as much as just thinking that The Apple was kind of a Eurovision-style song competition.”

But there’s another fascinating Idol connection here: “The funny thing is, Ken Warwick, the other executive producer of American Idol, is in The Apple,” Lythgoe reveals. Warwick in fact served as the film’s assistant choreographer. “There he is, in his full gold jockstrap, in the middle of [the musical orgy number] 'Coming.’ He was one of the dancers in the movie! He’s got a little sort of goaty beard. And [about 15] years ago, they carried it in a cinema down by CBS Studios where we were shooting American Idol, and the whole American Idol team and I went to go see it. Of course, when Kenny came on with his gold jockstrap, the whole place stood up and applauded.”

There seems to be another way that The Apple predicted the future — or at least, Lythgoe’s future career. In the film, the BIM powers-that-be enforce daily exercise, with all of society coming to a halt for mass jazzercise drills in the middle of the street. “It was the belief that music could control people and that we all need exercise, so the BIM was brought in and I had to choreograph this [number], when during the work hour or during school, everything had to stop in order to do your exercise — which is very Eastern, if you think about it, that everybody has to go into the park and do Tai Chi or whatever. It was based on the thought that the world needs to do this,” Lythgoe explains.

Similarly, in 2010, Lythgoe, along with Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, established National Dance Day, a government-recognised holiday that encourages citizens to dance for fitness in organised public spaces. Another coincidence, or no?

“My, this [movie] has ruled my life without me realising it. At least that's only one day a year,” Lythgoe chuckles when the similarity between National BIM Hour and National Dance Day is pointed out. “I think I should go lie down on a couch and just talk to you about this.”

Lythgoe confesses that while he “really didn’t like the script,” he was a fan of The Apple soundtrack (“The music we thought was terrific at the time; certainly the use of strings and the real violins and everything was just terrific and felt very inspiring to me”), and he was convinced that his Apple choreography would earn awards and acclaim. “All That Jazz came out the same year and went to the Cannes Film Festival with The Apple, and All That Jazz was actually in the Cannes competition. And I kept thinking, 'My God, am I really going to have to go up onstage in Hollywood and apologize to Bob Fosse for picking up the Oscar for Best Choreography?’ I was so dumb — because they don’t even do an Oscar for choreography!”

When asked about his favourite dance numbers in The Apple, Lythgoe mulls it over for a moment, then says, “I suppose the motorbike scene, the 'Speed’ number, which was the first time that we moved the cameras around. That was a lot of fun. And 'The Apple’ itself; there were just so many dancers and so much going on that I hadn’t really ever experienced with directing, because they let me direct the dance numbers. And then, of course, the sort of Busby Berkeley sex routine, 'Coming.’ Oh yes, very subtle lyrics in that song!”

Considering what a critical and commercial debacle The Apple was, it is a bit surprising that Lythgoe agreed to speak about its anniversary, but he good-naturedly explains, “I’ve learned more from things I’ve done that have not been terrific than I have from things that have been very successful. I made a program called Ice Warriors that I absolutely loved at the time, and it was such a failure that I didn’t have ice in my Scotch for three months afterwards! If you don’t make mistakes, you’re not going to learn anything. For me, success is being 51 percent better than my 49 percent of failures.”

So, what did Lythgoe learn specifically from the failure of The Apple? “I think, in truth, it is to not be writing scripts during the days you’re filming,” he laughs. “Make sure that you’ve got a complete idea in your head when going from point A to point B, rather than preambling around and then just losing the plot halfway through the movie, and then it’s like, 'Let’s make another plot up!’”

Well, that would explain the movie’s tacked-on, Rapture-like finale, when (spoiler alert!) a previously unseen godlike character named Mr. Topps randomly swoops in and teleports Alphie and Bibi to Heaven in his hologramic flying Rolls Royce. But Lythgoe reveals that in the original cut of the film, Topps was introduced much earlier on: “He was in the edit. He'd been there a while in the film that I made. But suddenly, somehow, when it came to it, he just appeared at the end of it.” (According to the film’s Wikipedia page, movie originally opened with a two-song “Paradise Day” prologue, depicting Topps carving Alphie out of a rock and dispatching his new creation down to Earth to meet Bibi. Yet that crucial, plothole-filling sequence never made it to the big screen.)

When asked if this strange, disjointed edit was made because test audiences possibly gave feedback that they wanted to see less of Mr. Topps, Lythgoe just quips, “My dear, if they had tested it with movie audiences, I don't think that they would have put the movie out.”

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Spotify.

Portions of the above interview are taken from Nigel Lythgoe’s 2015 interview for Yahoo Entertainment and his 2019 appearance on the SiriusXM show “Volume West.” Full audio of the latter conversation is available on the SiriusXM app.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies