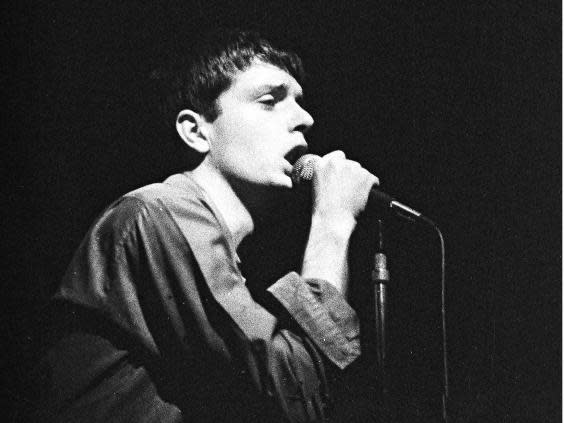

Unknown Pleasures at 40: How Joy Division and singer Ian Curtis changed what rock and pop could be about

It’s now 40 years since Factory Records released the debut album by a young Manchester group called Joy Division. Unknown Pleasures came out on 15 June 1979, less than a year before the band’s singer Ian Curtis killed himself. Their follow-up, Closer, would be a posthumous release.

Yet, at four decades’ distance, it still seems almost impossible. How could this album by a group of gawky Mancunian youths at the beginning of their twenties, still getting better at playing their instruments, turn out to be one of the greatest records ever made? The year before, they could be heard on the compilation album Short Circuit: Live at the Electric Circus playing punk thrash under their former name Warsaw, making an early incarnation of The Fall sound melodically sophisticated and Buzzcocks sound like Beethoven.

That live performance, of the song “At a Later Date”, recorded in October 1977, a year after the band formed but not released until June 1978, included the hollered introduction, “You all forgot Rudolf Hess!”. At the time, this reference to Hitler’s deputy only heightened the association of the band with Nazi imagery. Their debut EP, An Ideal for Living, also released in June 1978, had cover artwork depicting a member of the Hitler Youth, while their name itself was taken from a 1955 work of Holocaust fiction House of Dolls, about the sexual slavery of Jewish women in concentration camp brothels. It was an association that would take some time to shake. Bernard Sumner’s later adoption of a Hitler Youth haircut – which became the de rigueur post-punk hairstyle – and his styling of himself with a German surname, as Bernard Albrecht, which he later said was a mishearing of Bertolt Brecht, certainly didn’t help.

But musically, the leap between “At a Later Date” and Unknown Pleasures was astonishing. Of the four songs that appear on An Ideal for Living, released on their own Enigma label, the opening track, “Warsaw”, with its horrible “3, 5, 0, 1, 2, 5, Go!” intro shows the place where they were coming from. But the second track “No Love Lost” and the verse sections of track three, “Leaders of Men”, have already begun to show the space that exists within their sound. Both give an idea of where they might be going.

Significantly, where Joy Division were going included signing to Factory Records. Label boss and TV presenter Tony Wilson was key to their development. He saw them play live in April 1978, and promised to put them on Granada TV, which he did later that year. He also offered an escape route to them from record company RCA, who wanted to meddle with their sound. (Factory would meddle, too, it must be noted, but the results were wondrous.)

The two songs that appear on A Factory Sample in December 1978, alongside tracks by Cabaret Voltaire and the Durutti Column, show the rapidity of their progression. On both “Glass” and “Digital”, Peter Hook’s basslines have begun to vie for dominance with Sumner’s sparse guitar, but Curtis’s lyrics have advanced light years: “Feel it closing in/ day in, day out” he sings. The 2014 edition of his lyrics and notebooks, So This Is Permanence, shows an artist distilling his writing into phrases that plummet into the inner depths at the same time as they explode outwards towards universal experience. On “Day of the Lords” from Unknown Pleasures, you can see this process clearly – the jotted notes that form the lyrics include the lines, “I relaxed from the days filled with bloodsport in vain/ And returned with the knowledge that were two the same”. This almost cheerful couplet transmutes into the stuff of nightmares: “I’ve seen the nights, filled with bloodsport and pain/ And the bodies obtained, the bodies obtained”.

A Factory Sample was produced by Martin Hannett, a curly permed chemistry graduate, who had produced Buzzcocks’ seminal Spiral Scratch EP as Martin Zero. Six months after recording “Digital” and “Glass”, he and Joy Division would go into Strawberry Studios in Stockport, where 10CC had made “I’m Not in Love”, to record Unknown Pleasures. Strangely, if you look back, as a listener, it’s hard not to see the album’s iconic black cover with its pulsar wave form (designed without hearing the record by Peter Saville) as a doorway to the music. Darkness seems to permeate every groove. “To the depths of the ocean where all hope sank, waiting for you”, sings Curtis on “Shadowplay”, yet Joy Division were now fully formed as a rock band and the power of their music defies any attempt to categorise it as doomy or depressing.

Drummer Stephen Morris’s percussive instinct gives it the feel of a muscled beast poised to spring, and the battle for its melodic soul has been won, right from the start of the opening track, “Disorder”, by Hook’s bass, with notes played high up on the neck of the instrument. Sumner’s guitar comes in like an alarm, ringing with anxiety. There are no places to settle, no comfort zones, anywhere on Unknown Pleasures.

Hannett clearly becomes the fifth member of the group. On “She’s Lost Control”, he employs individually recorded drum sounds and concrete slabs of guitar, as well as echo effects that drag Curtis’s vocals down into an undertow of subhuman sludge or upwards towards hysteria. The band hated how he’d toned down their “loud and heavy” live sound, but he’d actually made it more powerful. (Hook would complain again at the “strangling a cat” guitar sound Hannett produced on “Atrocity Exhibition” on Closer – “I was like, head in hands, ‘oh f**king hell, it’s happening again,’” he later wrote.)

Aside from the electronic effects on “She’s Lost Control”, Hannett used techniques that created a sense of the music existing in a real, if empty, echoing space, the closing doors and smashing glass on “I Remember Nothing” create an atmosphere of creeping unease and violence. That same sense of fear pervades “Insight”, on which Curtis’s vocal was famously recorded down a telephone line. “I’m not afraid any more,” he sings… “I keep my eyes on the door”, he adds, suggesting otherwise.

Unknown Pleasures in some ways is still a bridge between the band they were – “New Dawn Fades” is surely the apogee of Joy Division as a rock band – and the more ambitious sound of Closer, but it remains utterly unlike anything else before or since.

Overcoming the sense of it being impossible to understand how Unknown Pleasures could come to be requires the ability to see disparate personalities converging on a moment in time. It’s tempting to view Curtis, a driven artist already suffering from epilepsy as the key to Unknown Pleasures. But would the album have sounded like it did if Curtis had not married his childhood sweetheart Deborah Woodruff, then moved with her to a house in Macclesfield, where she left him alone to write night after night in the blue room they had transformed specifically for that purpose? “Ian’s writing career was paramount for both of us,” she wrote later. Would it have happened if the band hadn’t come from the same city as Wilson, who had a vision of a new type of label, where “the musicians own their music” and had “the freedom to f**k off”, or if Wilson had not been partners with a little-known producer called Martin Hannett? It surely wouldn’t have sounded like it does. Unknown Pleasures is a monument to meaningful accident that created an entirely new idea of what rock and pop music could be about. Happy birthday.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies