'Ad Astra' director James Gray: Oscars are 'great celebration' of film, but they're a 'little silly'

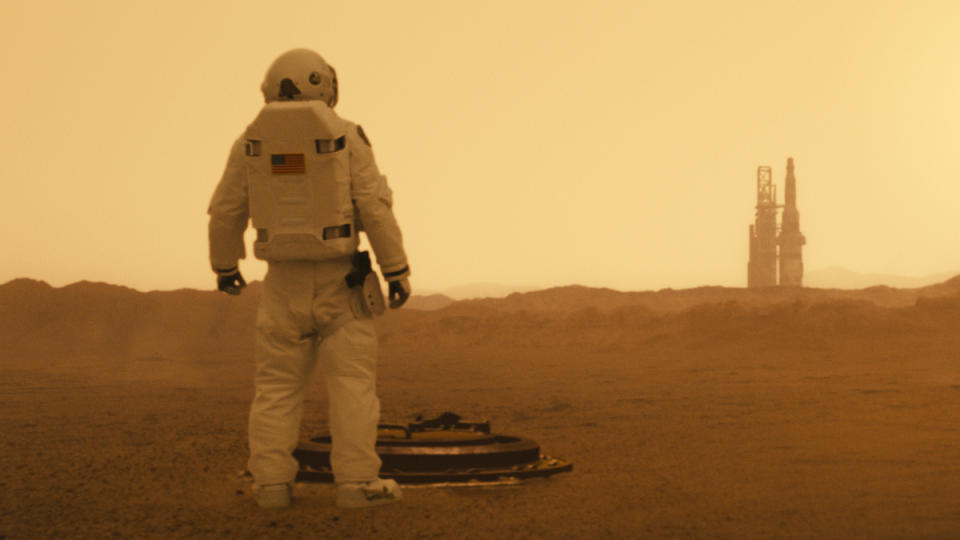

Ad Astra is no ordinary space film. James Gray, director of thoughtful jungle adventure The Lost City of Z, has crafted an intelligent take on interstellar exploration, powered by a true movie star performance from Brad Pitt.

Pitt portrays astronaut Roy McBride, who embarks on an arduous journey to Neptune in order to track down his father — years after he believed his dad was dead on a research mission — when strange signals begin to emanate from his last known location. It’s basically Apocalypse Now in a spaceship.

The star is already being talked about as a potential Oscars prospect, possibly facing off against Joaquin Phoenix — another Gray alum, who the director calls “a f**king genius” — for his work in Joker.

Read more: Gray calls Pitt an “underrated” actor

“I always feel like it’s a little silly,” says Gray about the awards season race. “At the Olympics, I can tell who the fastest runner is, but a movie? Best?

“It’s a great celebration of the medium, but I can’t weigh in [on the Best Actor race] because I haven’t seen [Joker].”

Gray is certain, however, that Pitt represents one of the last true movie stars and that it is the intangible quality of the 55-year-old that made him the perfect choice for Ad Astra.

Read more: Pitt didn’t realise he was playing a Nazi

He says: “When you talk about the last few movie stars and you say that Brad Pitt is a movie star, which he is, we’re really talking about that level of unreachability — accessible, but not that accessible.

“There’s a magic to how his face connects with the camera.”

It’s certainly a unique performance in a very special film.

Read the full interview with Gray, where he discusses depicting realistic space travel, the fading power of the movie star and the race to get his film finished before the Venice Film Festival. Ad Astra will release in UK cinemas on September 18, 2019

Yahoo Movies UK: I think Ad Astra is really interesting. We seem to have a wave of really thoughtful space movies at the moment, with things like Gravity and First Man. Were you inspired by these other space films?

James Gray: It’s a great question and I’m gonna tell you the honest answer, which is that it drives me a little crazy. I wrote the thing in 2011 and Chris Nolan, who’s a very good friend of mine and a great person, is very secretive about his projects. I said “what are you working on?” and he said “something space/science-fiction” and I kind of went “you are?”. Then I saw the movie [2014’s Interstellar] and I got all upset because he was using an organ and he did a bunch of other things I wanted to do. Then Gravity came out with a realistic depiction of space.

So the ambition was actually earlier than the films that are out now — and Damien Chazelle’s wonderful movie too. So I didn’t use them in the initial thought process, but it speaks to the interest level of the filmmaking generation. We are now able to look at something like the Apollo mission, for example, with enough distance that we can appreciate it.

Read more: Best sci-fi movies of 21st century

In 1969, a guy walking on the moon made you go “oh wow, that’s amazing, what’s for lunch?” but, 50 years later, I think it’s much easier to look at it and say it’s the greatest achievement in the history of man. People walked around on the moon with computing power less than your telephone. So maybe it’s that distance.

I guess that, at the time it happened, it felt like it was the start of something. And it still feels like the peak of human achievement.

I think you’re completely right, and I think the reason for that is that the motive of the Apollo missions was less than pure — it was to beat the Russians, it was connected to a sort of Cold War idea. And the minute we did it, and the Russians couldn’t, there was a sense of completion which makes no sense. We know this is true because Neil Armstrong, when Pete Conrad and Alan Bean did Apollo 12 back to the moon, he said that we’d have lunar bases by the year 2000 — and he was wrong of course, but he was right technically. We had the ability to do it. We just didn’t pursue it.

So you’re right. There was a level of “been there, done that” completion and there’s a sadness to that, that we didn’t keep pushing. But I think it’s coming back. We’re going to Mars in 2033, back to the moon in 2024, we’re going to build the Orion spacecraft in dry dock in orbit around the moon. The moon has only one sixth gravitational pull, so long-range rockets are going to take off from the moon, which is actually in the movie. It’s an idea based on what they think is actually gonna happen.

I think that, if we really focus our energies on going to Mars, that will rekindle something. Mars is very useful to us because it’s essentially Earth with climate change so we’re going to learn about what hopefully doesn’t, but probably will, happen to the Earth and how we can survive and manage that without being killed off like the dinosaurs.

You mentioned some very specific years there, but your film doesn’t specify a year. Did you ever consider picking one?

JG: We didn’t, and I’ll tell you why. I love Blade Runner and I love 2001: A Space Odyssey, both of which specify years. You watch Blade Runner and the Replicants are built in something like 2018 and we wanted our film to be very unspecific.

We didn’t want it to be about a prediction of the future. We wanted it to reflect in some ways the Earth as we know it now. We didn’t want to instantly date it in some timeframe and thought it was better left ambiguous as the near future.

You discussed the authentic space travel in other films and it certainly feels very authentic in Ad Astra. What measures did you take to ensure the space travel was as accurate as possible?

JG: Absolute madness! We tried as best we could, but at certain points you can’t be accurate. There’s no way to get to Neptune, for example, which is 2.7 billion miles away. You can’t get there in 80 days. So you have to ask yourself: okay, it’s not realistic, but is it plausible? Is the science plausible?

In the case of Chris’s movie [Interstellar], it’s interesting, because there is a theory about essentially a kind of warp drive system. It’s the Alcubierre theory. In theory, you could build it, although we’re not currently close to that. So we tried to say that, in theory, Neptune in 79 days with some sort of nuclear fusion propulsion we don’t have yet could work.

Read more: Exploring the original Interstellar script

The other stuff, we tried to keep accurate. The idea that long-range rockets would take off from the moon? They would, because there’s one sixth gravitational pull and needs less thrust. The zero gravity? The need for tranquilisers while travelling? The injection of the food directly into your system? With all of these things, we were trying to adhere to the actual science. You’re already asking the audience to suspend disbelief, so you want to give them a context where it feels real. If it feels fake, they just don’t buy it at all.

You have to do two measures. Either, the film has to feel completely real or it’s Star Wars with Ewoks and speeder bikes and cloud cities — something so fantastical that you’re never once asked to believe it. In between and you’re screwed.

I think that’s true, and one of the things I really liked about your film was the little details, like the moon being 50% tourist trap and 50% Mad Max. I thought that was really interesting.

JG: That comes really from a basic evaluation of the facts on the ground. The moon has huge amounts of natural resources, we think. We already know it has huge amounts of something called Helium-3. We don’t know the commercial applications of that yet, but we will probably find them. There will be international space treaties, but who the heck will be able to enforce those?

Half of the satellite is beyond our communications — the far side, not the “dark side” Pink Floyd, but we love you anyway — and it’s going to be the Wild West for part of it. It’s just going to be. There will be nation states setting up colonies and searching for natural resources, but who’s going to make the borders?

Read more: Jake Gyllenhaal thinks the moon controls us

So that’s a fact. Another fact is that you’re gonna need food there. You’re not going to be able to have cattle grazing and you’re not going to be able to grow plants easily because it’s one-sixth gravitational pull and you’re not sure how plants will react. So you need processed food and who runs processed food? Fast food chains, like Subway on the moon. You use the facts at your disposal to dictate what you think the near future will be like.

That detail really spoke to me. There’s a tragedy when you get to the moon and it’s like a service station. Then there’s the Mad Max chase...

JG: Which is very weird because you’re only hearing the sound that he hears. It’s weird.

I wanted to talk about Brad Pitt. For me, it feels like an old school movie star performance of the kind we don’t really get much any more.

JG: Well there aren’t many left any more.

Absolutely! And I think the one-two punch of Ad Astra and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood kind of cements him as one of the last movie stars.

JG: There’s him and there’s Leo [DiCaprio]. Maybe a couple of other people, but not very many. I watch old movies with my children a lot and I was watching It Happened One Night. I hadn’t seen it in 20 years. You look at the film and it’s very grainy black and white, it’s 1934, and you’ll see through the grain a scene where they’re at night and Clark Gable has put a blanket between them and he’s in one bit and she’s in another.

The light is just glinting and you see the reflection of a tear in Claudette Colbert’s eye and you realise that is what they refer to when they talk about the magic of the silver screen. It’s the ineffable, beautiful, unreachable, distant beauty.

And now with HD for example, or with 70mm Alexa cameras, the resolution is so good and so clean with digital protection — there’s no dirt. The light is no longer projected from behind you on to the screen. That level of abstraction that comes from the movie star is going away.

Read more: Hollywood breaks Tarantino record in the UK

So when you talk about the last few movie stars and you say that Brad Pitt is a movie star, which he is, we’re really talking about that level of unreachability — accessible, but not that accessible. There’s a magic to how his face connects with the camera.

There’s a shot right near the beginning, where space sort of fades into his face, as if he’s a celestial body himself.

JG: It’s the opening shot of the movie. And the whole point was that, if you go to the end of the Neptune, the contrast is beautiful as you try to look inside this man’s soul. In order to spend a whole movie with one person, part of it has to have that unreachable, inaccessible quality. As accessible as we want him to be, we want the abstract layer because that’s the magic.

This might be a massive reach, but the whole thing about his character in the film is that he chooses loneliness and chooses distance. Maybe that speaks to the movie star idea — that there’s a sort of enforced distance in that?

JG: That’s beautiful. I never thought about that. It’s interesting because the arc is that he chooses to be alone, but that’s very different from being alone. If I say to you that I’m going to have dinner and go to the movies by myself because I like that, that’s fine because that’s the luxury I have, to choose that. But if I’m forced to be alone, in a state of solitary confinement for example. It takes less than 30 days before serious mental illness sets in in solitary confinement. It’s a punishing, beyond torturous thing.

Read more: Brad Pitt demands ‘Straight Pride’ stops using his image

I think that, in the film, the arc is that he thinks he chooses to be alone but then, when he really is alone, it’s intolerable. He hears voices and he cannot stop his mind. I love what you say and I think it is, in some ways, semi-intentional.

It’s that untouchable thing about a movie star, and I’m not sure I can remember the last time I felt like that about a performance.

JG: I think he’s incredible in the movie. I don’t think it’s common now, because of what we’re talking about. There aren’t that many movie stars left and you can’t build a movie around them if you don’t have them.

DiCaprio’s a movie star. He has a different persona from Brad, thank God, because that’s why we have different movies. But he holds The Revenant together and that is a long film and a very grim film. You follow Leo because you love Leo. So movie stars do exist, but they’re in vanishingly small numbers. If you look at a movie from the 90s, for example, with Julia Roberts — who was a genuine movie star — she held the screen. There’s no amount of money you can spend to buy that kind of power if you don’t have it.

You know who would have been a movie star in the 70s? Joaquin Phoenix. He wears his inner turmoil on his sleeve, and we love to watch our actors suffer in the most beautiful way. That has a power to it as well. But it’s becoming almost unheard of now.

I was actually intending to bring up Joaquin, because Joker arrived at Venice at a similar time to your film. It’s very early to talk about the “O” word, Oscars, but it could theoretically be a straight fight between Joaquin and Brad for an acting trophy, and you’ve obviously worked with Joaquin before on The Immigrant.

JG: Unfortunately, I’m so ignorant about it because I haven’t seen Joker. I’m really frustrated because I had an opportunity back in Los Angeles two weeks ago, but I finished Ad Astra only two and a half weeks ago. Three and a half weeks ago, the visual effects supervisor looked at me and said I had 306 shots left to approve, so that should give you an idea of what I was facing before Venice.

So I haven’t seen Joaquin’s performance. I have no doubt that he’s great in the movie. The guy is a complete f***ing genius. Obviously you get different things with Brad and Leo, but then Joaquin has a different sort of power to him — that turmoil, that indecision and that danger is right there on the surface. The whole point with Brad is that he’s a classic, very masculine figure so we try to destroy that in the film. We try to say that his emotional reserve is his form of cowardice. He has great bravery — his heart rate never goes above 80bpm — but in the face of his father, he’s a little boy. You couldn’t make this with Joaquin, because he’s already there at the beginning. Each actor brings a different mythology.

Read more: Joker reviews laud film as a “masterpiece”

As for them battling each other, I always feel like it’s a little silly. At the Olympics, I can tell who the fastest runner is, but a movie? Best? In the 70s, they had one Oscar show — which I believe was produced by the director William Friedkin — and he had them remove the word “best” so they just said “the Academy Award goes to...” and he was heavily criticised for it.

It’s a great celebration of the medium, but I can’t weigh in because I haven’t seen the movie.

Ad Astra will release in UK cinemas on 18 September, 2019

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies